Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Disguising microbes to unleash an immune army against cancer

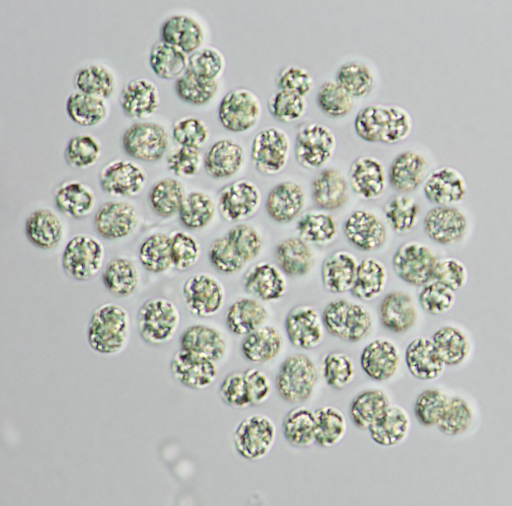

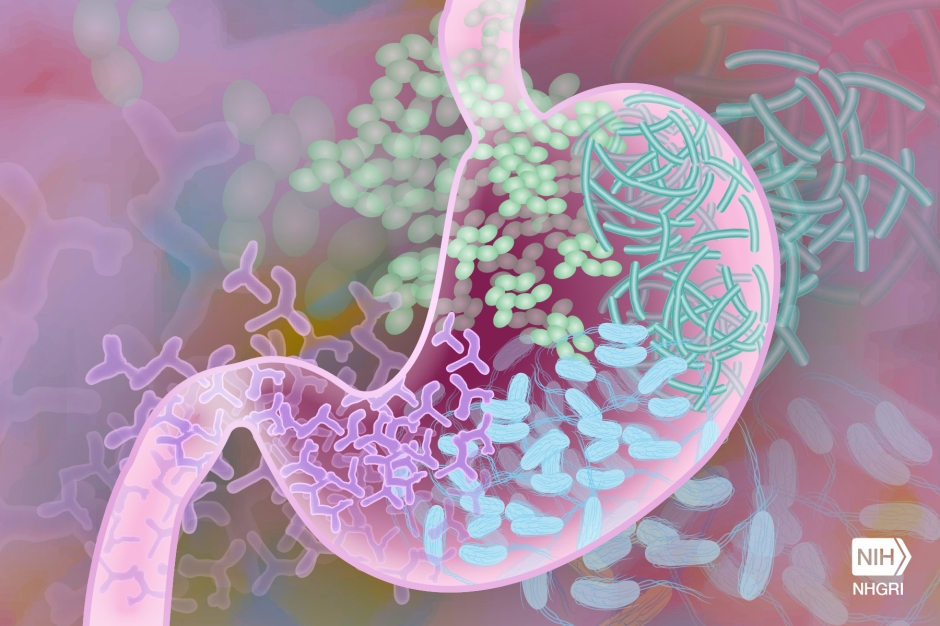

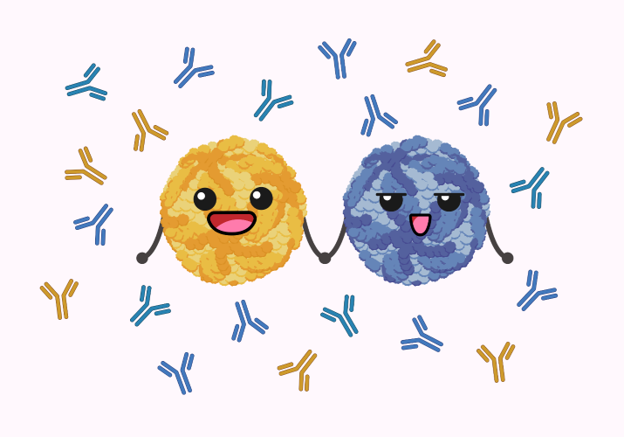

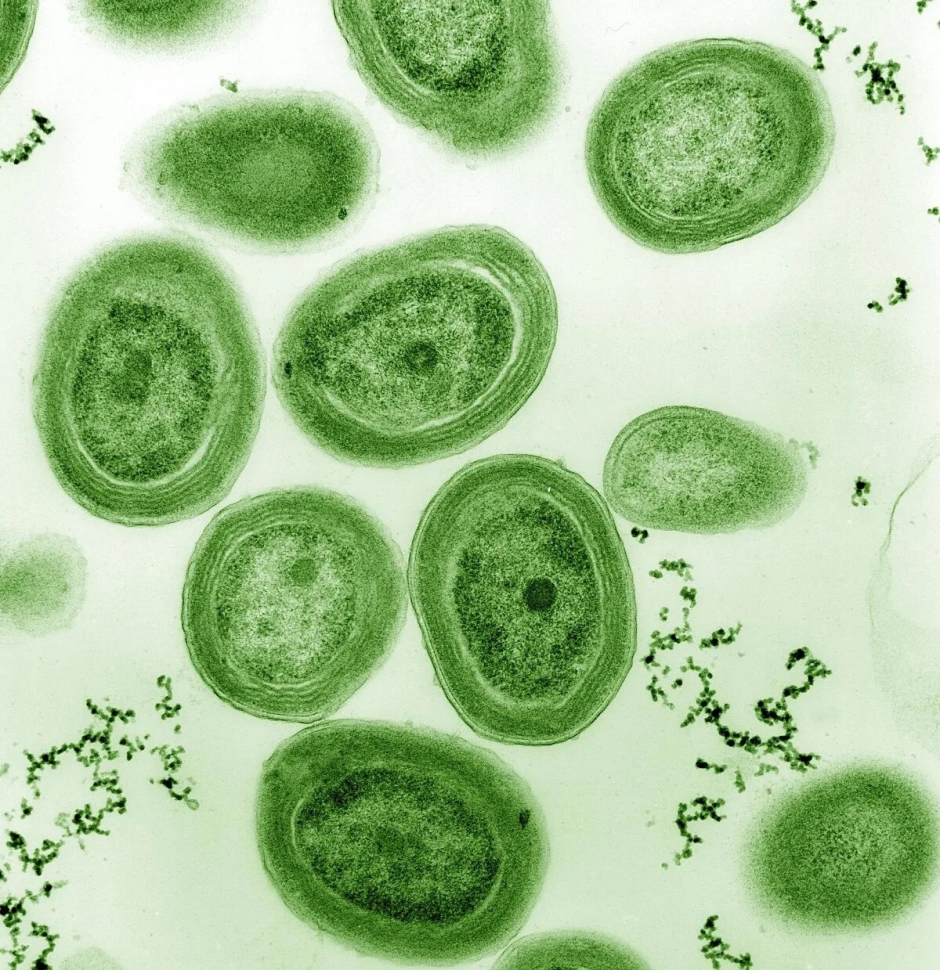

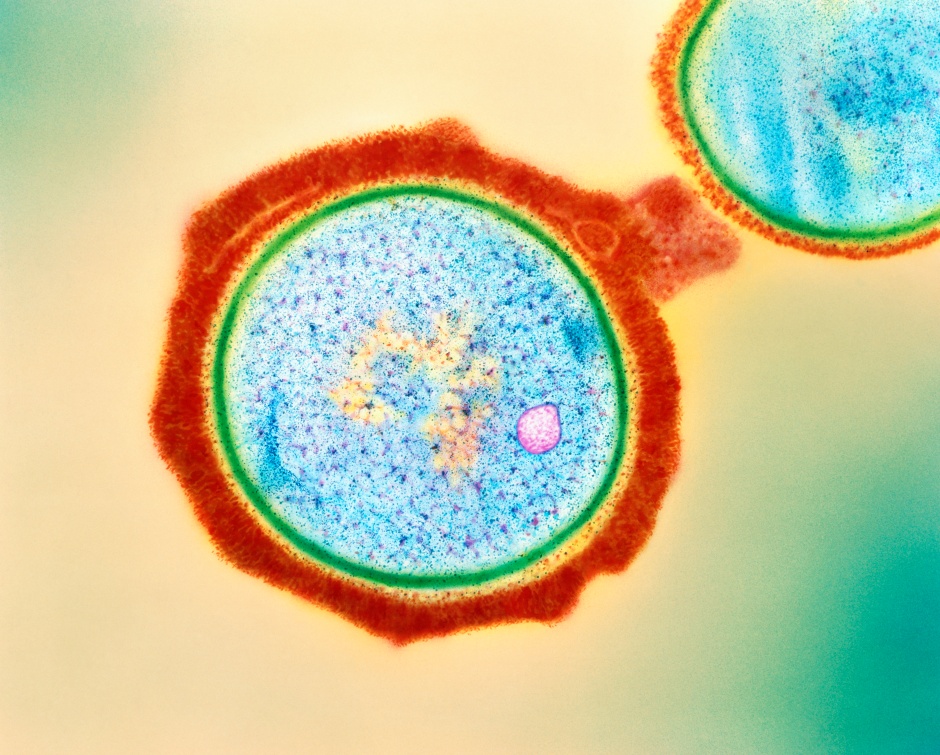

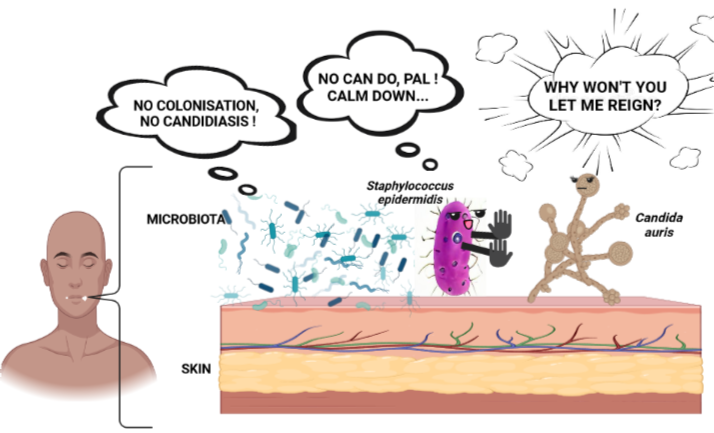

Microbes coexist within our bodies. There are many mechanisms in the human body that enable this to allow good microbes to stay in harmony with us while fighting against the bad ones. It is the immune system’s duty to ensure that it correctly identifies what is a good and a bad microbe and appropriately reacts. Staphylococcus epidermidis is one such good bacteria that is widely present on all of our skin. (Read more about these special bacteria here and here). When a patrolling guard (immune cell) recognizes someone coming near the border, they identify it. Based on the identification of the approaching individual, the army prepares to respond – whether they welcome a friend or prepare to fight off a foe. Analogous to this, the immune system prepares cells to either tolerate (welcome) or kill (fight) based on the identification of the microbe.

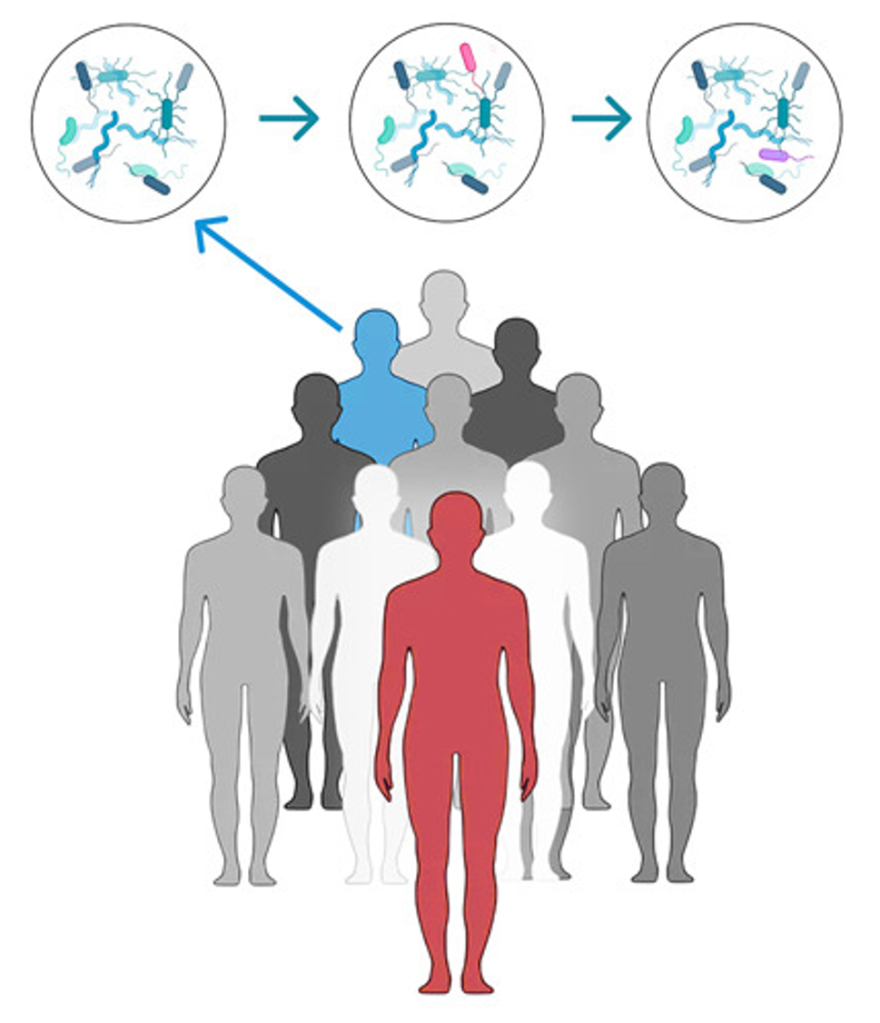

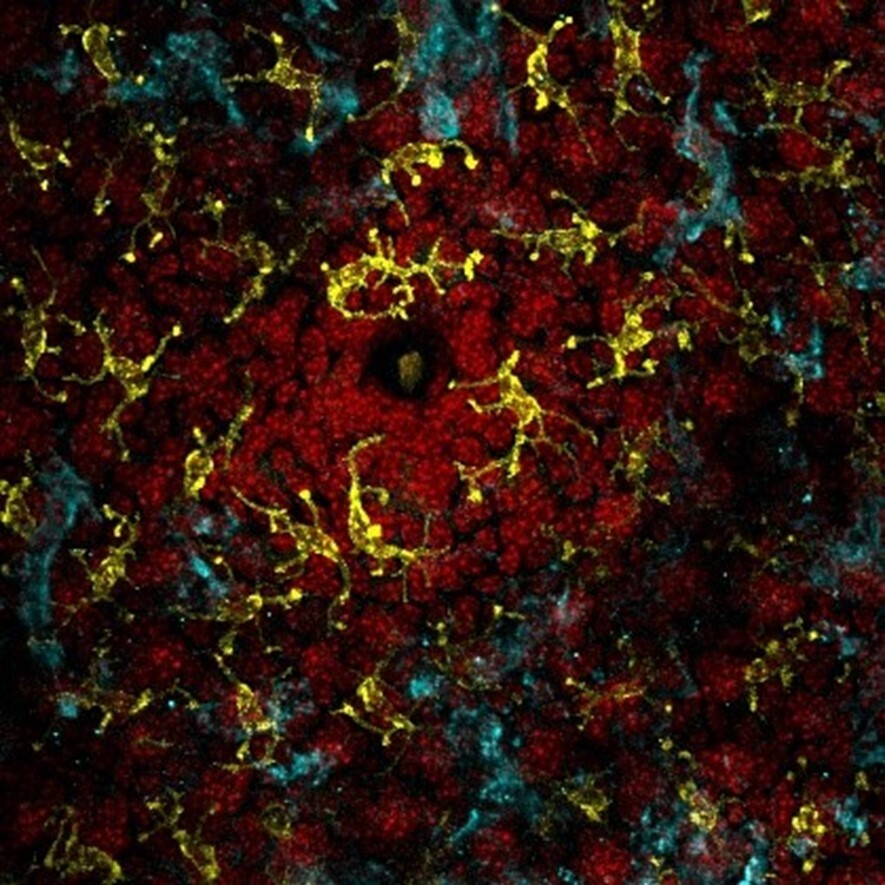

Not much is known about the nature of immune cells called to respond to this bacterium, particularly in the cells that express CD8+ marker (cytotoxic cells). However, the field knows that these immune cells help maintain homeostasis (harmony) and enable accelerated wound recovery (which is a surprising function of these immune cells). The authors decided to ask a challenging question: Can they use this microbe-specific response of immune cells to target tumor cells, which normally can hide from the immune system?

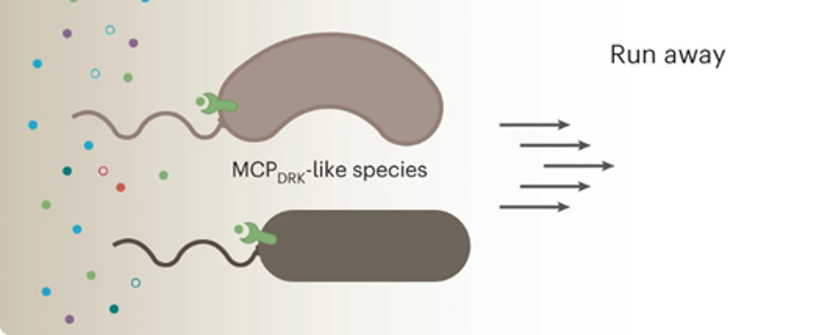

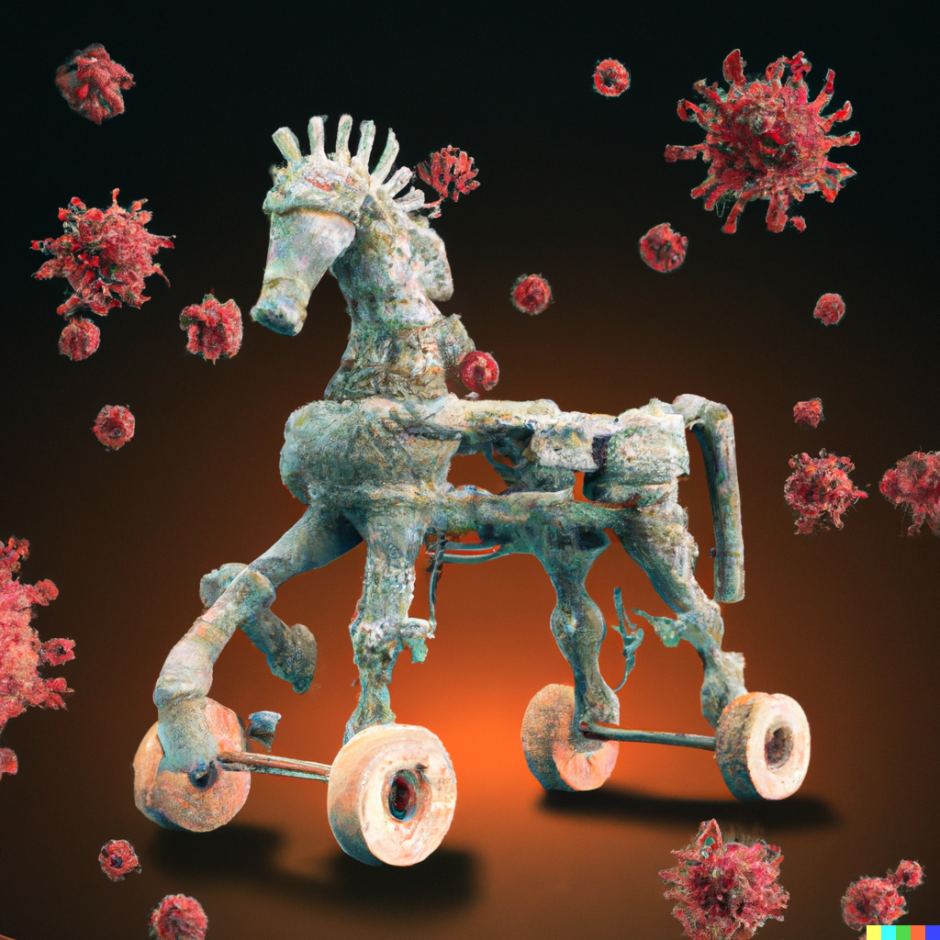

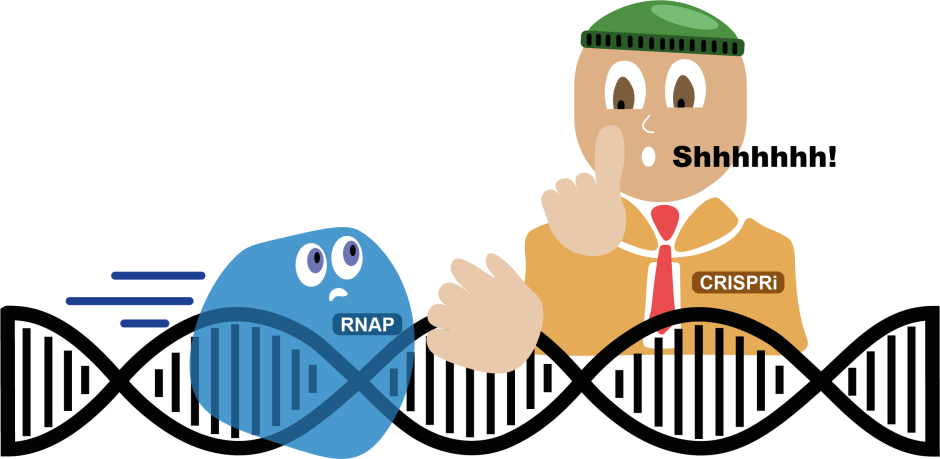

The authors engineered S. epidermidis to express an antigen (a part of the protein that elicits an immune response) that is normally found in a tumor, essentially masking the microbe to look like the tumor. So, the patrolling guard calls out to the army and alerts them to prepare for war. Normally, a tumor can be well hidden and already within the nation, avoiding alerting the army. But here, since the microbe wears a tumor costume, the army is alerted about the tumor. There is heightened security which allows the army to find the tumor and attack it. The authors then utilize a mouse model to understand how the immune cells react to these bacteria and tumor.

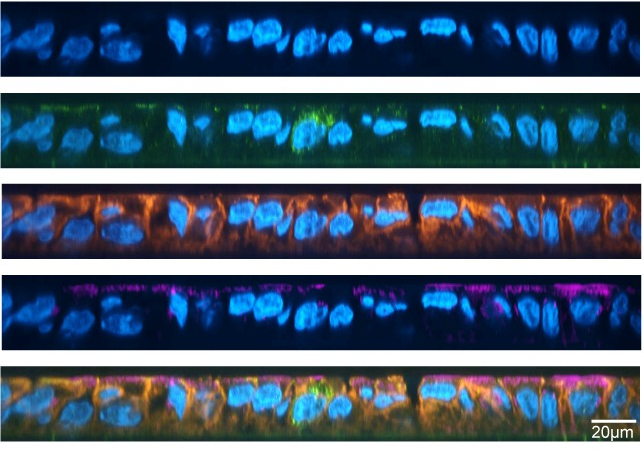

Let us try to understand this better. The microbe needs to actively colonize the mice and needs to be alive. Why is this important? Well, would a patrolling guard alert the army about a dead individual outside the nation? Not really! So now there is a microbe dressed like a tumor. The patrolling guard sees the tumor as an active invader and a threat to the nation and alerts the army. Everyone in the army is notified, and war preparation starts. These army soldiers are looking all through the nation for the invaders (tumor) due to the heightened security state. When the soldiers find the actual tumor, even though it is far away from the microbe anatomically, they are able to attack and fight off the tumor, in combination with immunotherapeutic drugs (drugs that modulate the immune cell function), i.e., in the analogy, help from the government to shield themselves against the invaders.

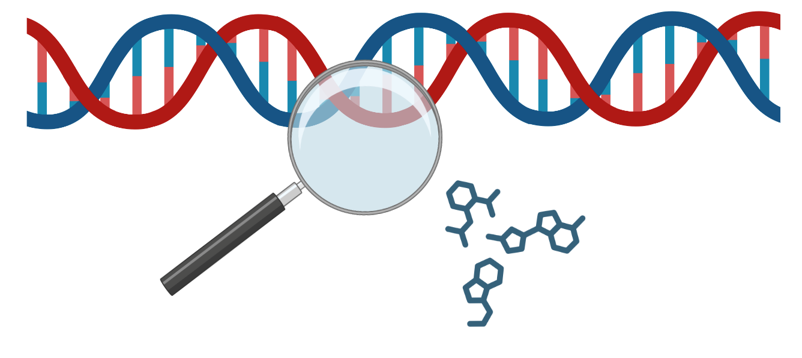

In fact, the authors conducting the study did show this (immune cells successfully fighting off the tumor) in two settings: one where the tumor was implanted after the microbe colonized (this is analogous to having mice immunized to cancer, so it is similar to vaccination), and secondly, when the microbe colonized after the tumor was implanted (offers more insight on designing therapeutic strategies post diagnosis of cancer). This has profound implications for cancer therapeutics. If we can understand the tumor antigen, i.e., what the patrolling guard uses to recognize the invader as a tumor invader, then we can engineer bacteria to express the same antigen and simply introduce the bacteria onto the skin. This, in combination with existing immunotherapeutic drugs, can result in an effective immune response against the tumor, without any unnecessary infection or inflammation. This offers some advantages over potential cancer vaccines because the antigen stimulation (the time period for which the invader is visible to the patrolling guards) is longer and more durable, resulting in better immune responses.

Link to the original post: Y. Erin Chen et al. Engineered skin bacteria induce antitumor T cell responses against melanoma.Science 380,203-210(2023).

For more information on S.epidermis

Featured image: Made by author on Biorender.com