Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

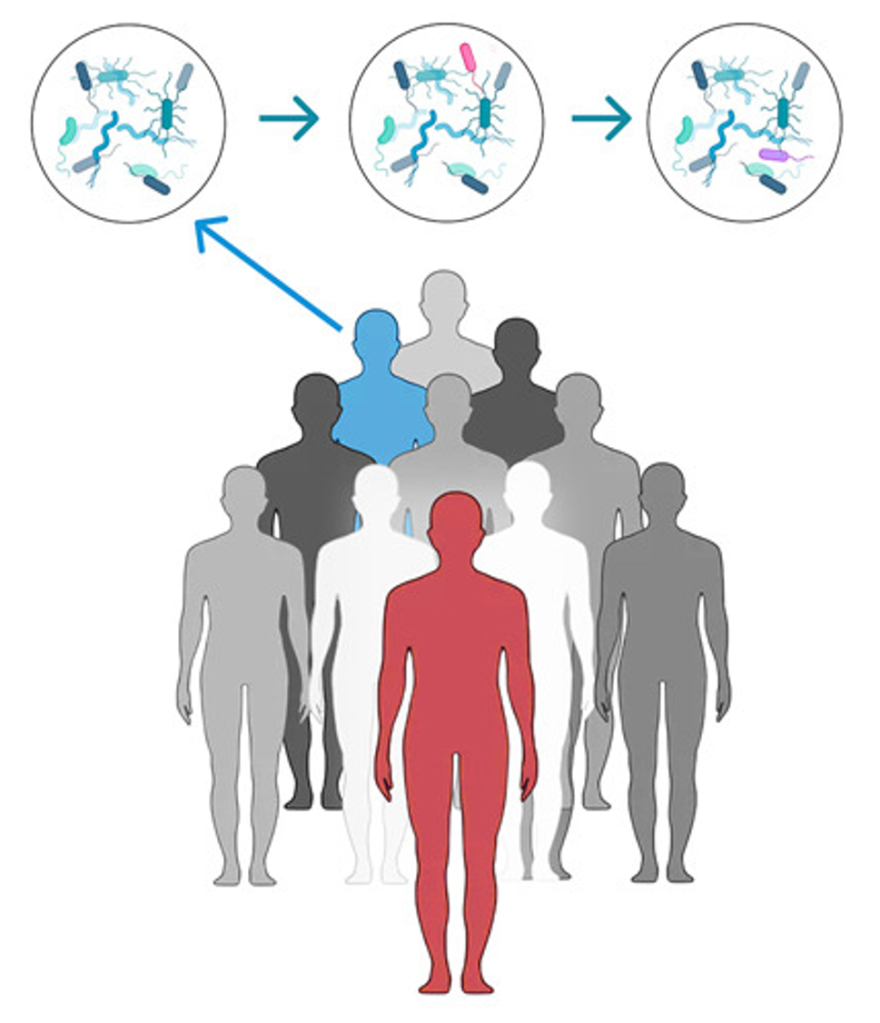

Transmissible microbiomes

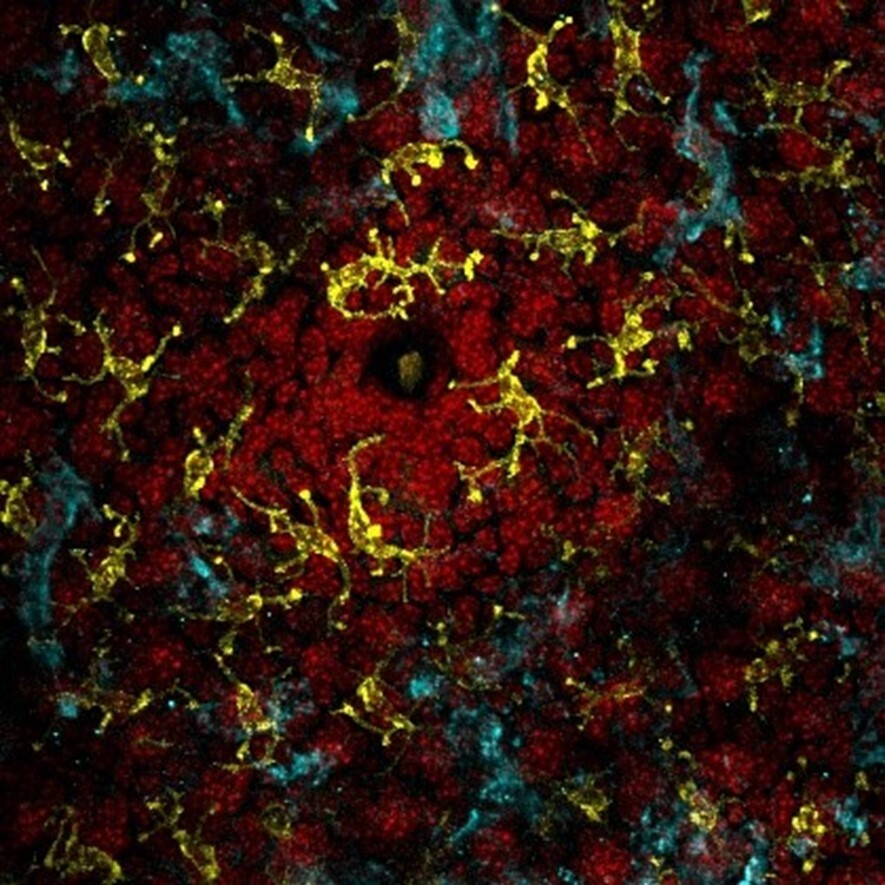

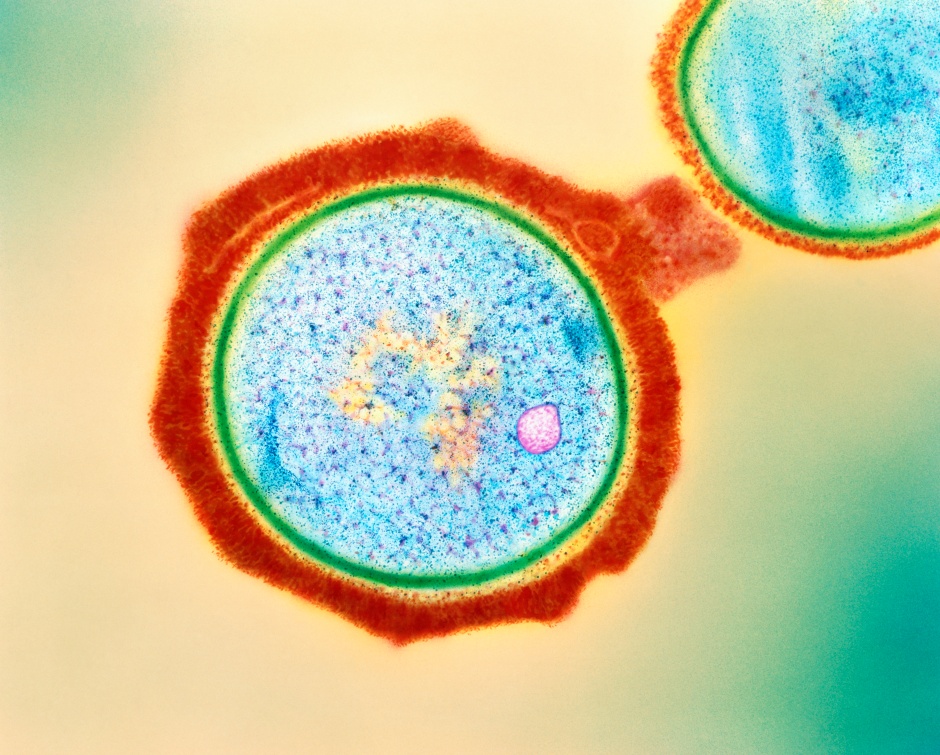

Decades of research have made it clear; we are humans as much as we are microbes. Outnumbering human cells in our body, the human microbiota – the collection of microorganisms harboured by each person – has gained increasing attention over the years as a key player in human health and diseases.

Being shaped by a lifetime of events, diet and environmental factors, unique microbiomes develop in various sites of our body, such as the oral microbiome in our mouth, and the gut microbiome in our intestine. This complex network of microbes is highly personal to each of us, and dynamic, as it continuously adapts to the events taking place in its host, our body.

But how do we acquire the members of these dynamic microbiomes in the first place? Most of these bacteria can hardly even survive outside of the human body! And can our inner microbes also be transmitted to people around us?

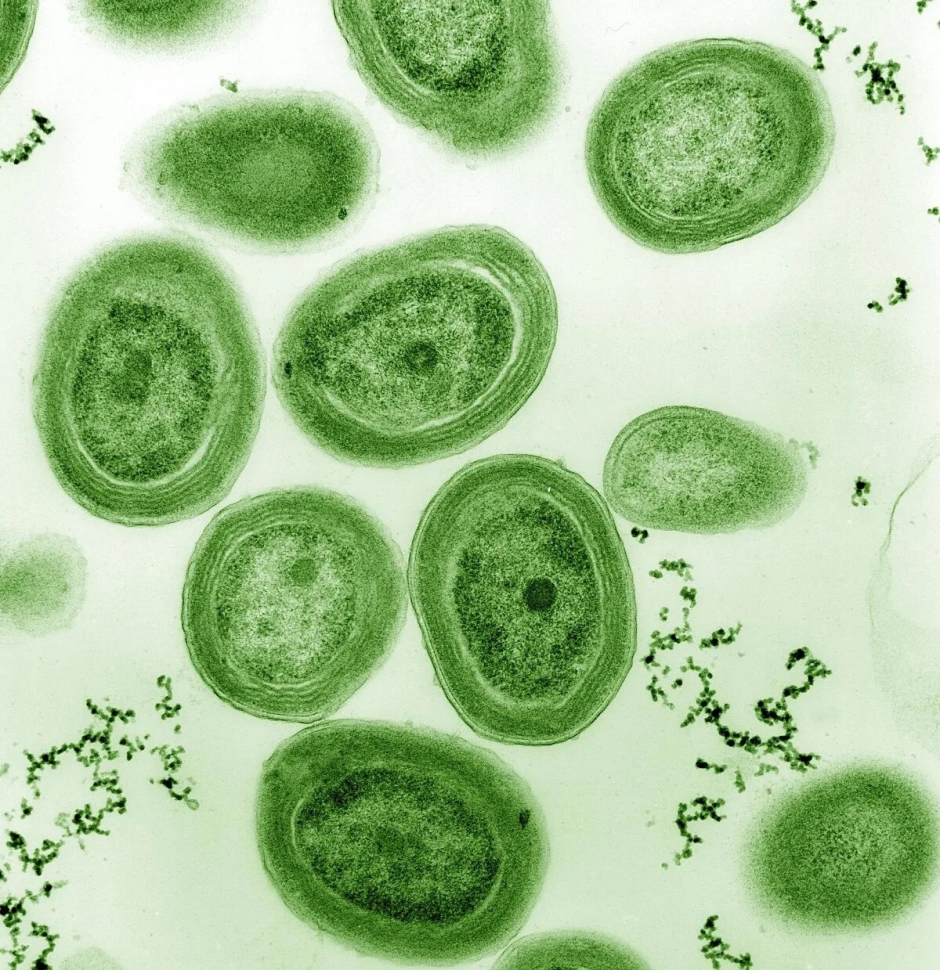

To address this question, researchers at the University of Trento looked at bacterial compositions between and within households and within villages, using data from 20 different countries across five continents. The research group refined a computational methodology allowing characterization of bacteria at “strain level”. Bacterial strains are groups of microorganisms belonging to the same species but sharing some unique genetic characteristics. Being able to confidently discriminate at a strain level can be pivotal when interpreting microbiome data, allowing for identification of patterns that could otherwise be overlooked.

The results of the study were recently published in Nature.

So, where do these microbes come from?

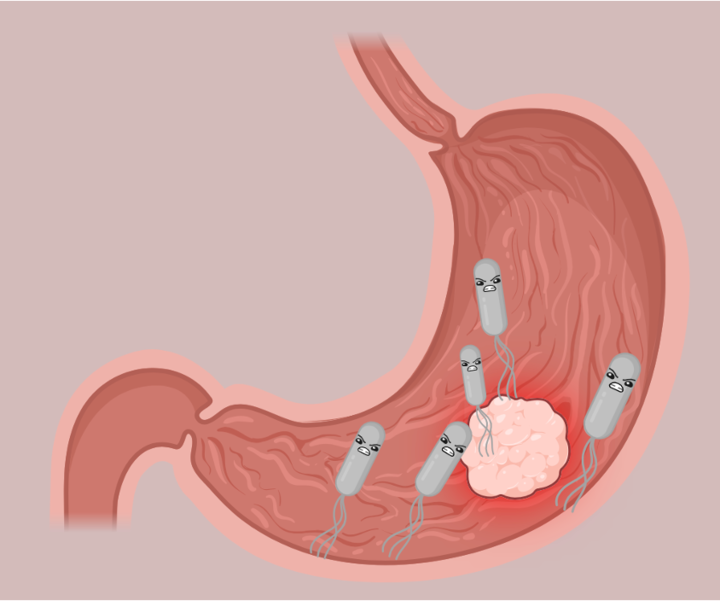

GUT MICROBIOME

When we are in the womb, our body is free of microbes. Our first contact with the outside world, and microbes, happens during delivery. The study found that over 50% of the gut microbes that a vaginally delivered baby acquires during the first year of life come from their mother. This is significantly less in babies born by C-section, highlighting vaginal delivery as a main transmission route in early life.

As we grow older and become less physically intimate with our mothers these numbers decrease, although a certain number of gut microbes remain in common even when we are adults. This may prove a long-lasting effect of maternal microbes imprinting at birth, or is a result of shared social environments later in life. Interestingly, certain species of microbes such as Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium are more likely to be transmitted from mother to child than others.

Now, the role of mothers is undeniable. What about the other members of the household, or even the population? Does horizontal transmission of gut microbes -that is, transmission of microbes between people not in a parent-child relationship- occur, or are similarities in gut microbiome merely due to similar diets and living conditions?

The study found that when adults live together for a long time, they tend to share more of their microbes with each other. Even people who didn’t grow up together, like romantic partners who only started living together in adulthood, share a surprising 13% of gut microbes.

Interestingly, when children grow up, they gradually start to share fewer microbes with their family members, and more with people outside of their family, because they are exposed to a wider variety of microbes over time.

Curiously, the same Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides species which were found to be highly transmitted from mother to infants were also highly transmitted across members of the households. These species might be efficient spreaders despite the transmission mode.

Genetics is certainly not to be forgotten when studying the transmission of microbes; identical twins retained higher microbes-sharing rates decades after living together compared to their fraternal counterparts. Nevertheless, we are now getting more and more evidence that living together plays a larger role in adult microbiome transmission than genetics and age.

So, strain sharing with housemates appears to be driven by close physical interactions, but how far can the person-to-person transmission of microbes go?

Surprisingly, quite far! When scrutinising gut microbiomes of the different populations included in the study, an intra-village microbe-sharing pattern emerged. This was absent in individuals belonging to different populations, or even to different villages of the same population. Microbiome transmission within the village is certainly substantially lower compared to the households, but we can’t neglect it. Considering the effect of social interactions in shaping the human microbiome could in fact shine a new light on defining whether several diseases currently considered non-communicable are in fact so.

ORAL MICROBIOME

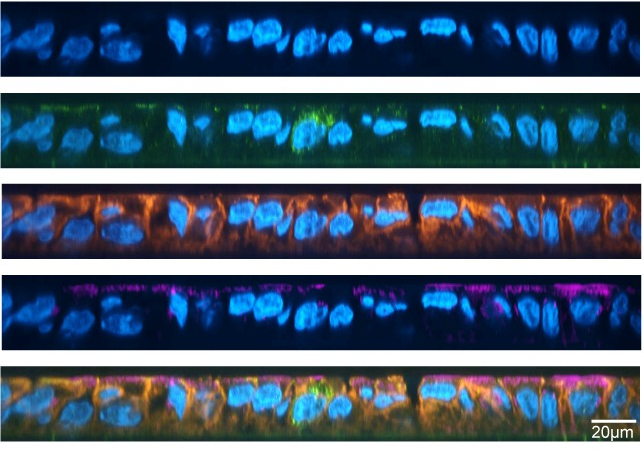

The collection of genomes of microbes residing in our mouth constitutes the oral microbiome. This is the second largest microbiome in our body after the gut, and bacteria residing here can be involved in a variety of infections; from the most obvious tooth decay and gum diseases to less evident diseases like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.

Supposably using saliva as a vehicle, the study confirmed that oral microbes can be more easily transmitted than gut strains, with a remarkable 32% of microbes shared among people living together, reaching even 38% for partners.

Microbes residing here appear to be horizontally transmitted rather than seeded at birth. Indeed, differently from the gut microbiome, the number of oral microbes shared between mother and child increases with age, as the overall population of oral microbes in the baby is also gradually increasing. The baby still acquires more oral microbes from the mother than the father, but this is likely due to closer contact and breastfeeding. The extent of the interactions rather than kinship appears to be what defines the transmission of the oral microbiome in the household.

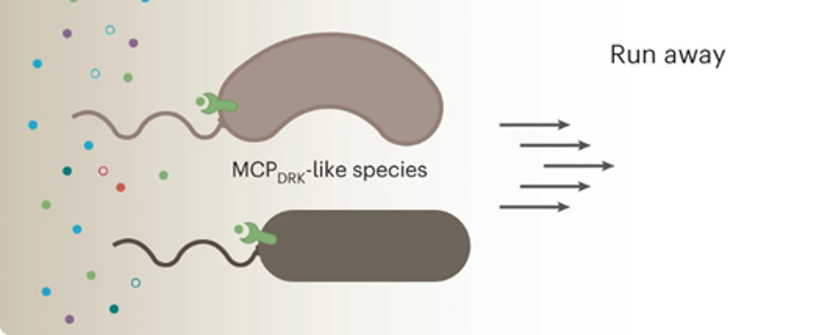

PHENOTYPES DRIVING THE TRANSMISSION

As we previously learned, transmissibility appears to be species-specific independent of geographical regions and lifestyles. When looking closer at species frequently transmitted, researchers noticed that these were not the most abundant in the population, but rather the ones possessing certain phenotypic properties. This was more prominent for microbes found in the gut rather than the mouth. In households, gram-negative bacteria, usually showing some resistance to cleaning agents, are more often transmitted. When microbes are transmitted across a greater distance in population, their ability to survive in the environment becomes more important – such as being aerotolerant and capable of forming spores.

To sum up:

- Our gut and oral microbiomes are dynamic ecosystems shaped by a lifetime of events unique to each one of us, but also acquired by close person-to-person contacts.

- Maternal seeding is responsible for over 50% of bacterial acquisition in infants, and a certain amount of gut microbes sharing between mother and offspring is retained till adulthood.

- Living together plays a large role in determining microbes sharing among individuals, most likely driven by close physical interactions.

- A low but relevant person-to-person transmission of microbes takes place even between unrelated individuals of the same village, calling attention to the role of social interactions in shaping the human microbiome and opening the door to a re-evaluation of diseases traditionally considered non-communicable.

- Transmissibility of bacteria is mainly strain-specific and driven by phenotypic properties supporting survival in the environment.

Link to the original post: Valles-Colomer, M., Blanco-Míguez, A., Manghi, P. et al. The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes. Nature 614, 125–135 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05620-1

Featured image: Created in Biorender