Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

The Tale of The Monkey That Ate a Man’s Food

As the morning sun shines through the canopy, an orange-tufted head with a peculiar blue-grey face emerges from the temperate forest branches of mountainous Southwest China. The golden snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) of Sichuan comes out to forage in the morning and enjoys a sundry of plant foods such as buds, flowers, leaves, bark, and lichen. However, declining habitat and increased human meddling are causing difficulties for this animal and their guts. A recent study stresses the importance of gut microbial ecology in captive and human-influenced animal populations.

The gut microbiota of animals is an important predictor of their health and plays a pivotal role in the nutrition and physiology of wildlife. Captivity and artificial food provide support for the rapidly declining populations of several IUCN Red List species, especially the Golden Snub-Nosed (classified as endangered).

However, even these measures have shortcomings. A human-provided diet can never accurately imitate nature’s basket, and the subsequent loss of gut microbial flora could result in long-term changes to the monkey’s health, impeding rehabilitation efforts. Captive monkeys continue to suffer from gastrointestinal illnesses such as diarrhea and dyspepsia.

R. roxellana has fermenting forestomaches (unique to colobine monkeys and other animals) that play a critical role in digestion and nutrition, highlighting the significance of investigating gut microbial polymorphisms and sensitivity. Additionally, like a mother passing down her foraging wisdom, there seem to be influences from pedigree relationships on the gut microbiota of primates. Host factors (i.e., the characteristics of the monkey hosting the microbes) like age and gender also impart some effects.

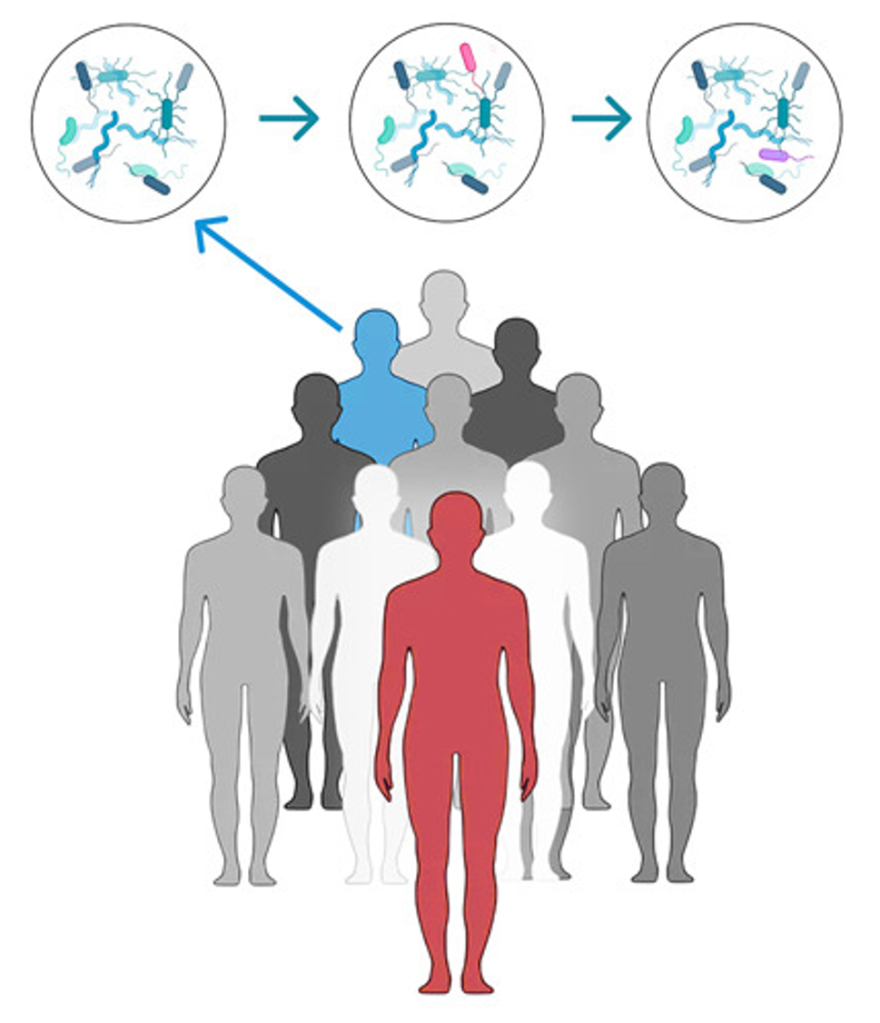

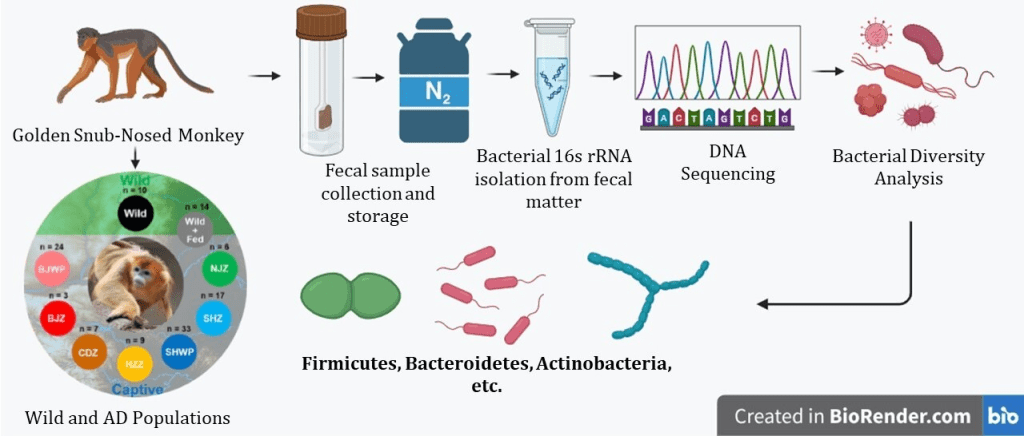

Only recently has serious research, to corroborate all the above details, begun. One such study is the comparative analysis conducted by Liu X. and cohort. In their investigation, they highlight the differences in gut microbiome between AD (anthropologically disturbed) monkeys and natural populations. They also reveal how the microbiota of human-fed monkeys is gradually shifting, similar to that of our commensal bacteria. Moreover, they shed light on the weight of host physiology and ancestral linkage on gut health.

Getting into the Monkey’s Business

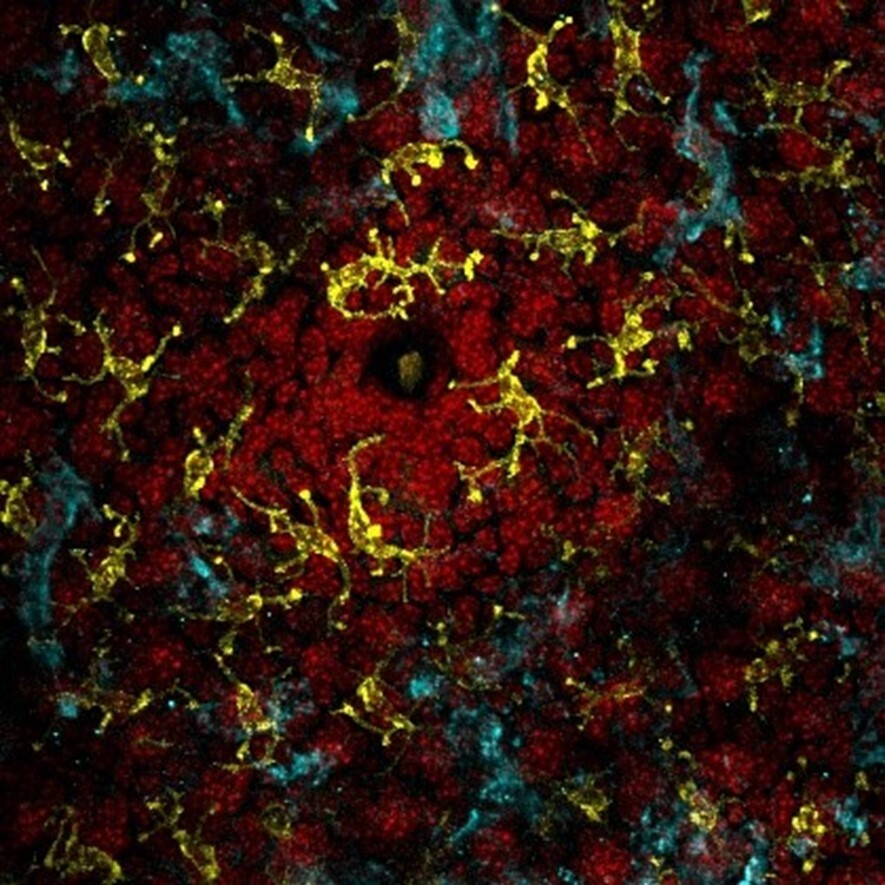

A total of nine groups of monkeys were examined without inflicting any stress or harm on them. One group was completely wild, one was wild but had some access to human food, and the remaining seven were captive, independent groups. Fresh fecal samples were taken immediately after defecation with a sterile spoon and cold-stored. After that, 16S rRNA was amplified and the nucleic matter was sequenced to identify the bacterial diversity of each group. Infant monkeys approximately 30 days old were excluded from the study because they do not yet have a stable gut flora.

The Tale of the Monkey’s Gut

The study found that both captivity and artificial food availability led to significant changes in gut flora, with diet being the predominant cause. The AD populations all showed the same overall shift in microbial diversity. There was an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Tenericutes. Additionally, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio declined in the monkeys. A higher ratio is associated with superior energy extraction from the food.

AD individuals’ gut microbiome exhibited higher vitamin and amino acid metabolism but lower antibiotic production and secondary metabolite degradation (mainly available from lichen and bark). The decrease in microbial antibiotic biosynthesis in captive individuals contributes to more frequent occurrences of digestive issues. Bacteria associated with the digestion of complex carbohydrates, cellulose and insoluble polysaccharides decreased. As a result, there was a drop in the coarse fibre present in the gut.

The cocktail of all these factors together explains why captive individuals are more susceptible to gastrointestinal problems.

Crucial Takeaways and Impacts

Monkeys, our primate cousins, encounter gastrointestinal troubles when their surroundings and feeding habits change dramatically, much as we humans do. As a result, the gut health of animals is a hot topic among conservation scientists. Conservationists are deeply concerned about the contradiction of supplementing dwindling food options with food from humans, which ultimately leads to additional difficulties in semi-wild and confined populations.

This study advocates using the animal’s gut microbiome as a health assessment criterion to help optimize breeding conditions for the captive population. This research provides critical assistance to wildlife conservationists when selecting nutrition options for their animals in captivity and rehabilitation.

Link to the original post: Original Article: Liu, X., Yu, J., Huan, Z., et al. Comparing the gut microbiota of Sichuan golden monkeys across multiple captive and wild settings: roles of anthropogenic activities and host factors. BMC Genomics 25, 148 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-10041-7

Featured image: illustrated by Anuradha Joshi using Krita 5.1.0