Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Exploring the vaginal microbiome

What do the microscopic organisms that live on your body say about you? How do they reflect your unique personal history, life stage and choices? And how might these microbes be affecting or reflecting your health?

Recently, researchers from the University of Antwerp, Belgium published a study to address just those questions, specifically focusing on the microorganisms that inhabit the vagina.

What is the vaginal microbiome?

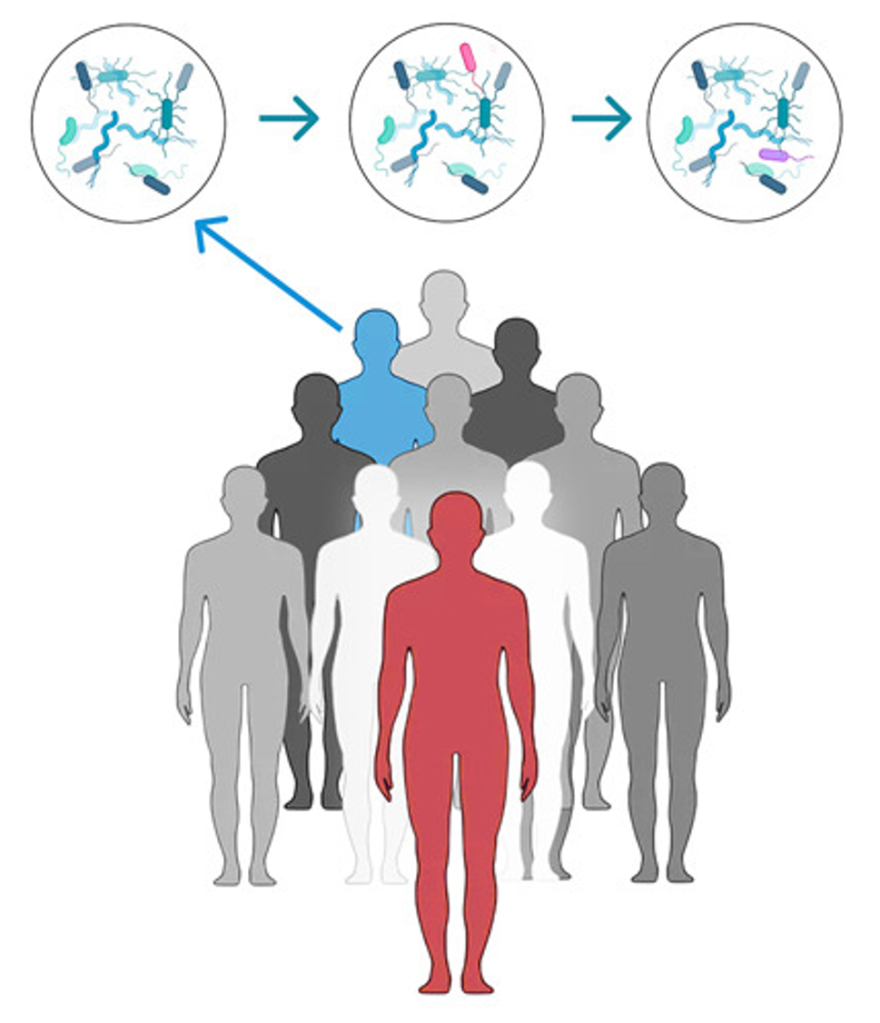

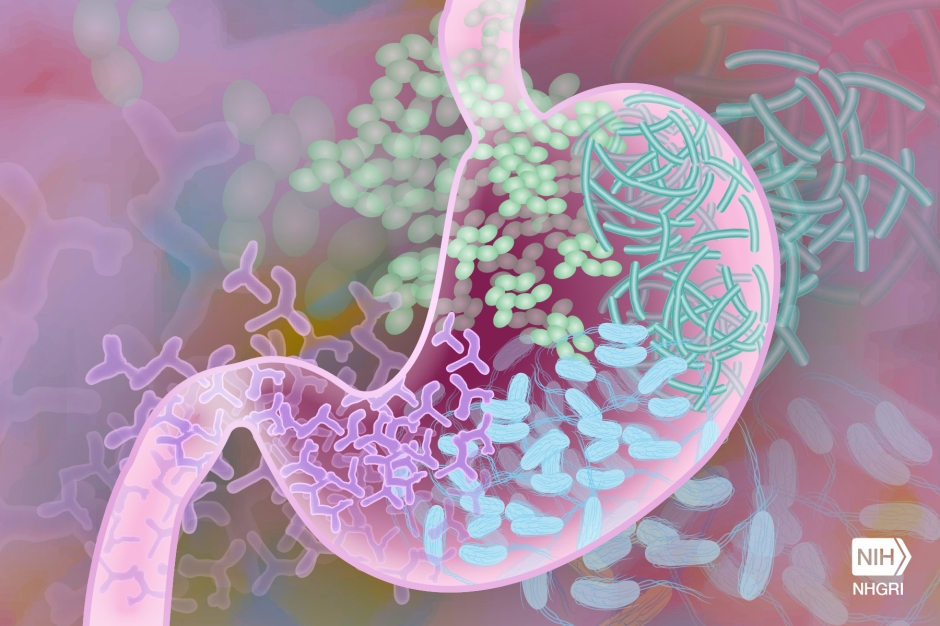

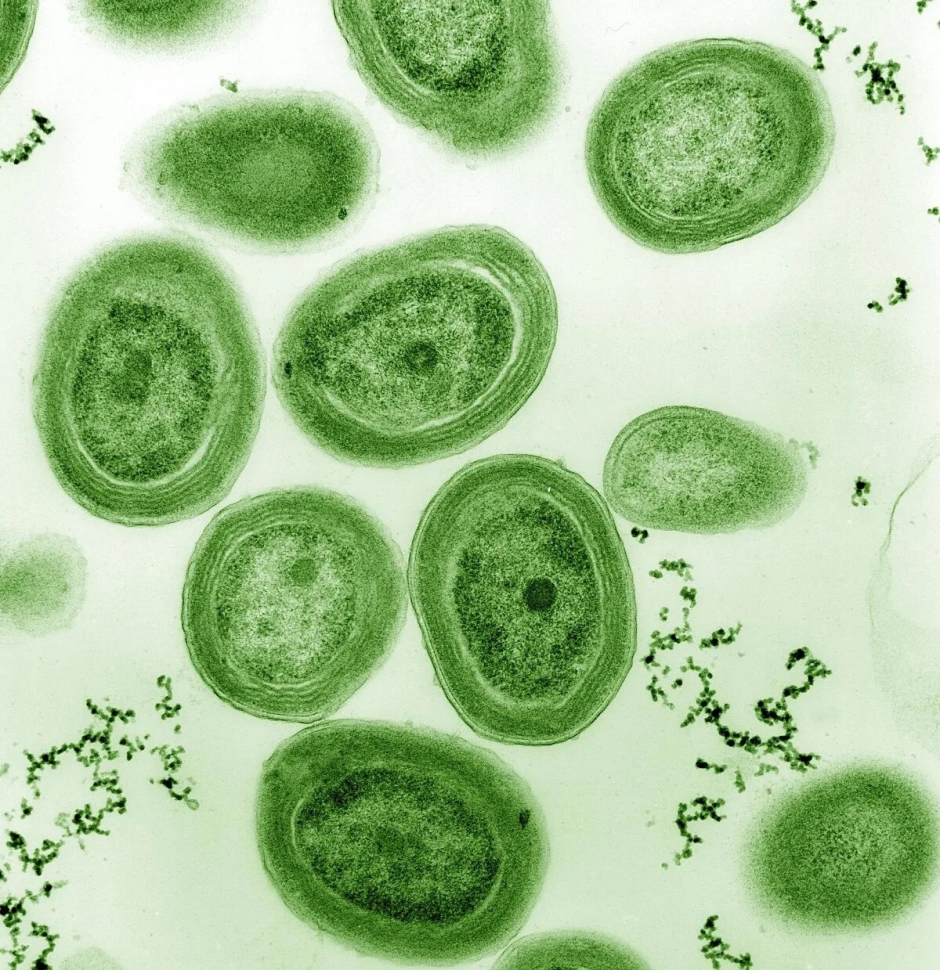

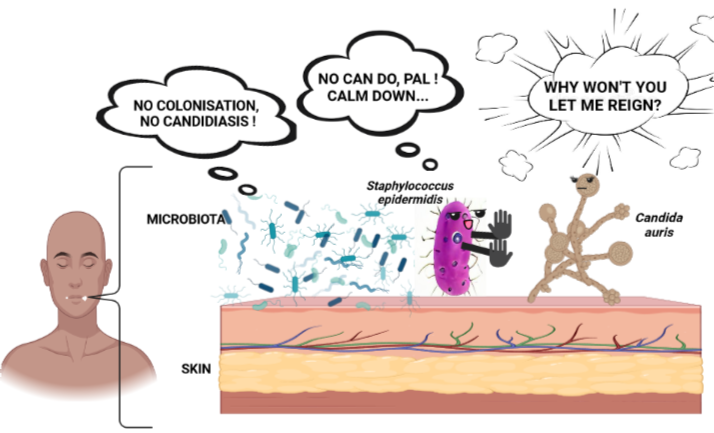

Every surface of every person’s body is teeming with life. Many different species of microorganisms cover every inch and crevice of our bodies, inside and out. This collection of microorganisms on the body of a larger organism is known as the microbiome, and we all have one. Not only that, but each of our microbiomes is as unique as a fingerprint. No one has the exact same set of organisms in their microbiome as you.

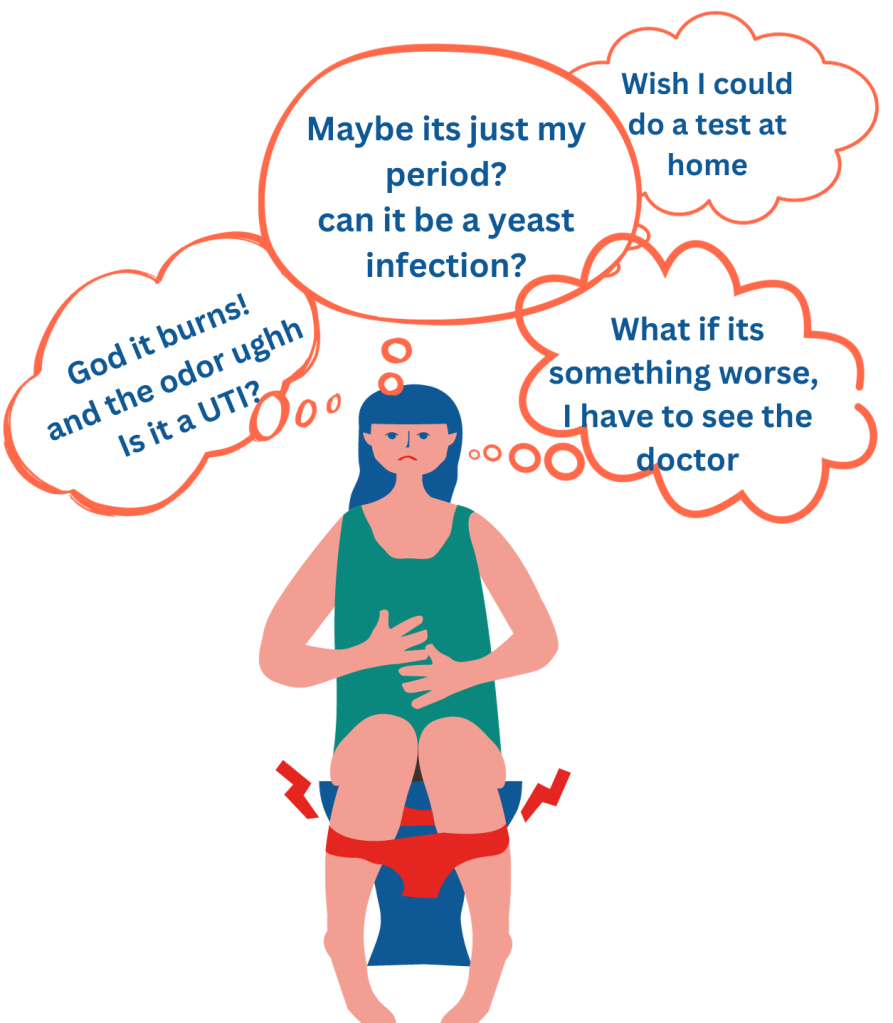

Different parts of the body host different types of microbes in different combinations as well. Your nose likely hosts a very different set of organisms than the bottom of your big toe. The researchers of this recent study wanted to better understand the microbiome of the vagina, what sorts of microorganisms inhabit it, how microbiome composition differs between people, and how features in the vaginal microbiome might be related to a person’s lifestyle and personal history.

The findings showed that the makeup of the vaginal microbiome is linked to a variety of factors including age, childbirth, partnership status, diet and more.

An ambitious citizen-based science study

This citizen-science study relied on sample contributions from the general public, and was named the Isala study, in honor of Dr. Isala Van Diest, the first woman doctor in Belgium. Most participants were from northern Belgium and were given self-sampling kits so they could collect vaginal swab samples from the comfort of their homes. This study was a relatively large compared to most vaginal microbiome studies that have come before, encompassing 3,345 participants.

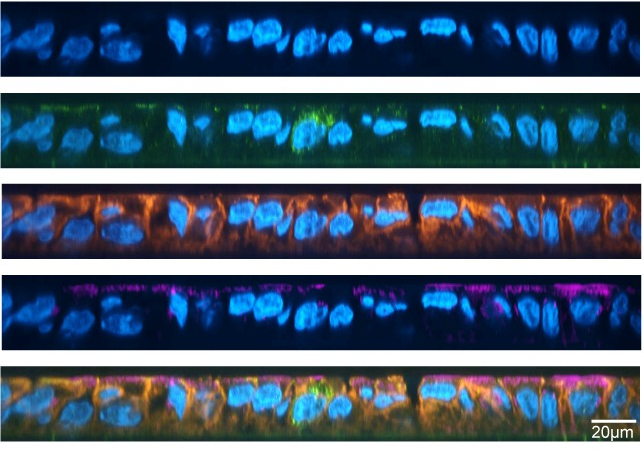

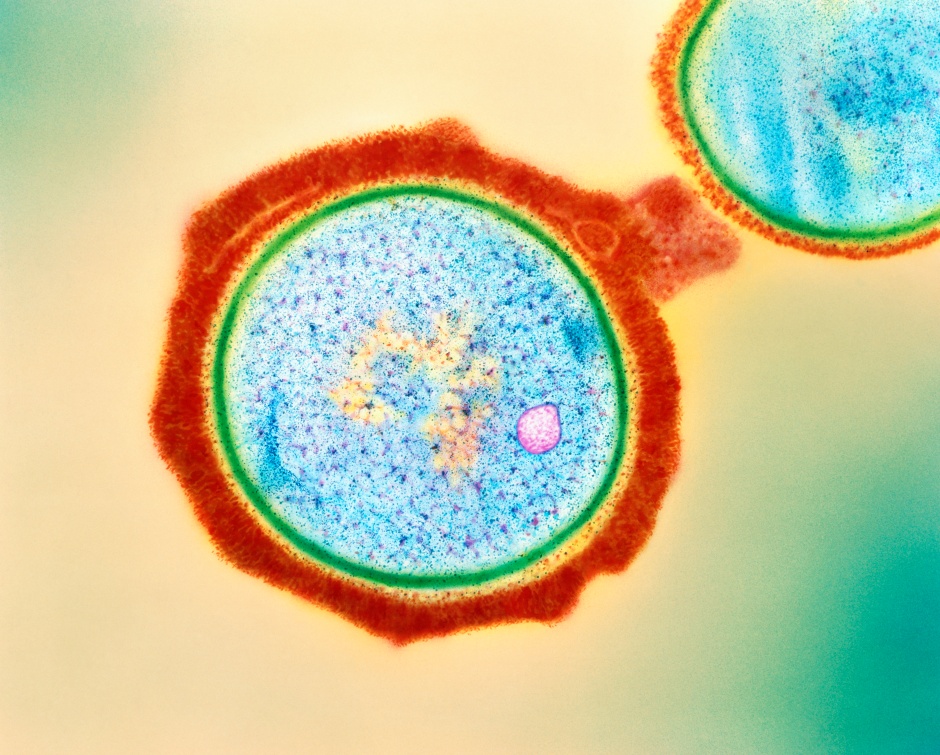

Once the researchers obtained the samples, they identified different types of bacteria in each sample by amplifying and sequencing the 16S rRNA genes, which are present in all bacteria. To be confident about their results, they also sequenced the samples using a different technique known as shotgun metagenome sequencing, which gives the entire genetic sequence of every gene in every organism present in each sample.

Finding patterns across vaginal microbiome samples

Previous studies of the vaginal microbiome had separated vaginal microbiomes into discreet categories called Community State Types (CSTs) based on which species of bacteria were dominant. However, this study observed that these microbiome samples could be more accurately understood as falling along a spectrum instead of neatly into separate categories.

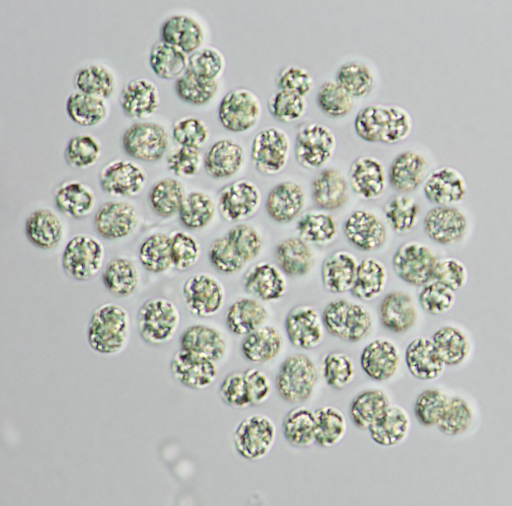

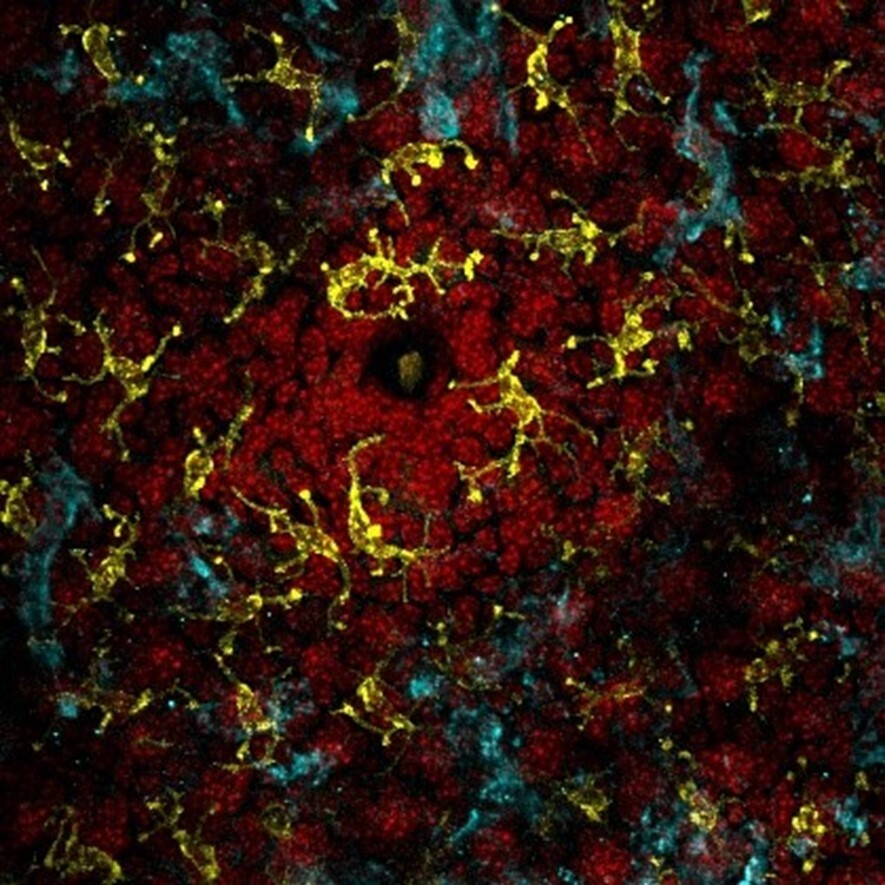

Bacteria from the genus Lactobacillus have been known for many decades as the dominant category of microorganisms in the vaginal microbiome. The results of this study agreed with this previous finding and showed that bacteria in the Lactobacillus genus were dominant in 78% of the samples. The dominance of bacteria in the Lactobacillus genus has been known to indicate or be associated with good vaginal health.

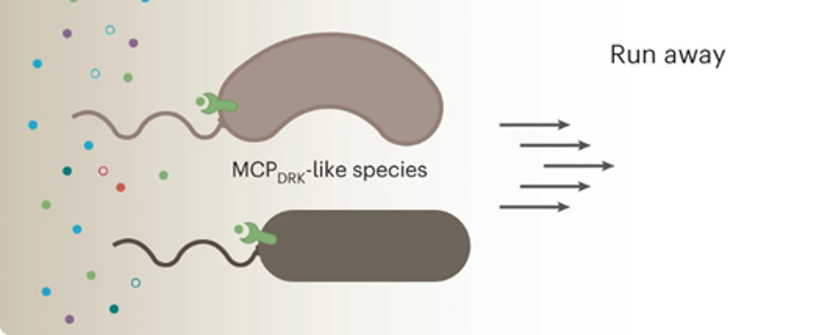

However, the researchers conducting this study found that the specific species within the Lactobacillus genus tended to covary with other species of bacteria, meaning that different species of Lactobacillus tended to be seen more or less frequently with other bacterial species than with others. The researchers called the groups of bacteria that tended to covary with one another “modules.” They claim that these modules are a better way of describing the differences in microbiomes than putting them into separate categories.

For example, the researchers noticed that in samples where the bacterial species Lactobacillus crispatus was the dominant species, the species Lactobacillus jensenii, and Limosilactobacillus tended to be present more often. They named this the L. crispatus module. Additionally, in samples where Prevotella was present, they saw a higher abundance of more than a dozen other species, and named this the Prevotella module.

The vaginal microbiome reflects lifestyle and personal history

In addition to vaginal microbiome samples, the Isala study asked participants for information about their lifestyle and personal history, including their age, partnership status, whether they had had children or been pregnant, menstrual cycle phase, sexual activity, diet, substance use, and more.

One notable trend the researchers noticed was that the study participants that had the L. crispatus module present in their microbiome tended to have fewer negative vaginal symptoms and higher levels of oestrogen, a marker of vaginal health and younger age. This module was also more prevalent in participants partnered with a woman.

On the other hand, women who had given birth to children tended to have reduced amounts of the L. crispatus module bacteria, as well as an increase in types of bacteria known to be common in the gut microbiomes of babies.

The researchers also observed higher frequencies of the Prevotella module in subjects that had recently had sexual intercourse, were menopausal, or were in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle.

More to be done

These valuable insights into the vaginal microbiome are only the beginning of the benefits provided by this study. The data these researchers collected will be available for comparison and further analysis by future studies of the vaginal microbiome.

The Isala study described in this paper does have shortcomings that prevent the results from fully reflecting human vaginal microbiome diversity. The participants who contributed their samples were all volunteers, and it is possible that those willing to volunteer were more likely to be in good health. The participants were also required to speak Dutch, and were residents of Belgium which limits the diversity of results as well.

However, work is already being done to address some of these limitations. Leading up to this publication, the researchers behind the Isala study have been open with the research community about their efforts. This has encouraged similar studies in communities around the world, which collectively call themselves the Isala Sisterhood. These more recent efforts have been launched across several continents in remote and low-income areas, which have not previously been represented in vaginal microbiome research. These additional efforts have been established in Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda, Peru, Switzerland, and more, and have received support from the original Isala study.

Further studies will also need to be done to understand the associations that were found in this study. While these researchers identified modules of bacterial species that contrived together, it is still not understood why these bacteria tend to be present together or why they are correlated with the participants’ lifestyle and personal factors. Additional studies will be needed to understand why these associations occur and how they might be used to support human health.

Link to the original post: Lebeer, S., Ahannach, S., Gehrmann, T. et al. A citizen-science-enabled catalogue of the vaginal microbiome and associated factors. Nat Microbiol 8, 2183–2195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01500-0

Featured image: Bing Image Creator