Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbes in stressed environments: to each, its own!

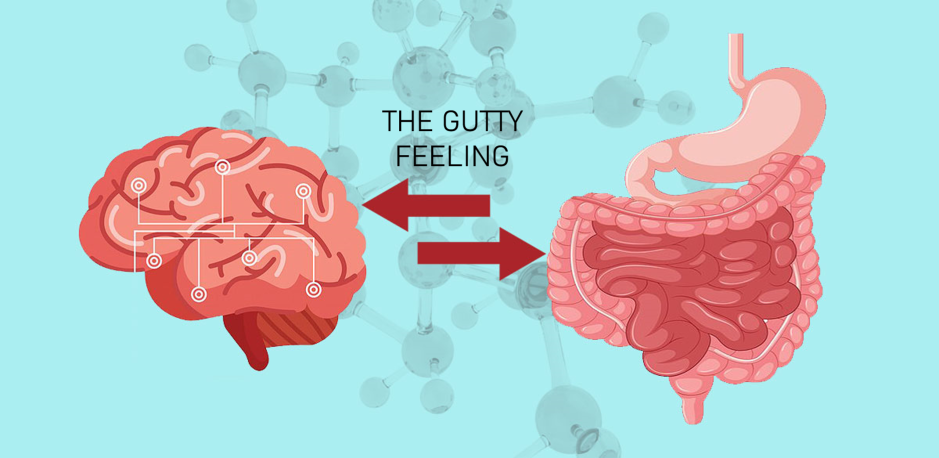

Imagine a ‘nearly’ empty landscape in the prehistoric era. Several communities of living beings are trying to establish themselves on this landscape. Which will succeed and flourish? Which others will perish? While we cannot answer this question for all living beings and the plethora of landscapes that surround us, we can gain some insights into how well microbial communities in the human gut colonize the intestinal landscape. But that is………easier said than done!

A healthy gut and its microbiome

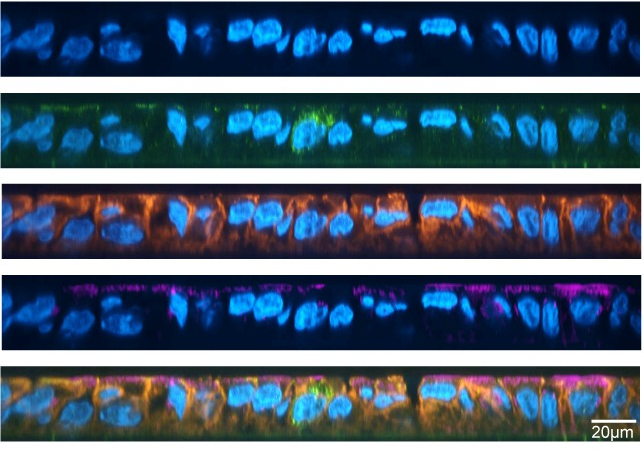

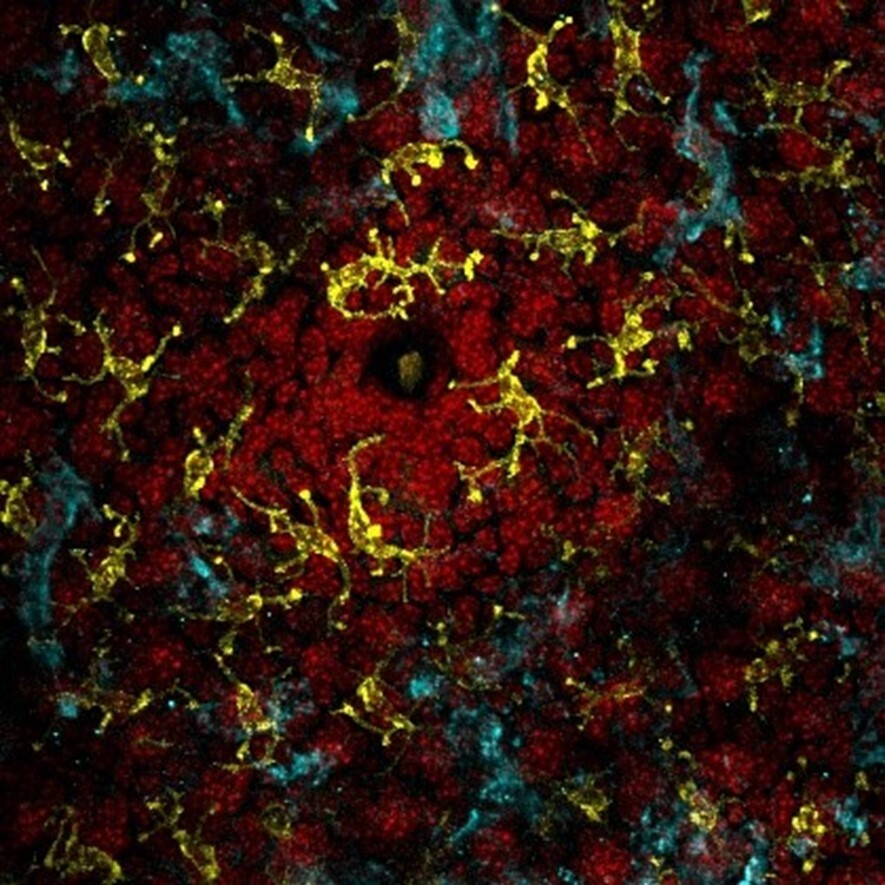

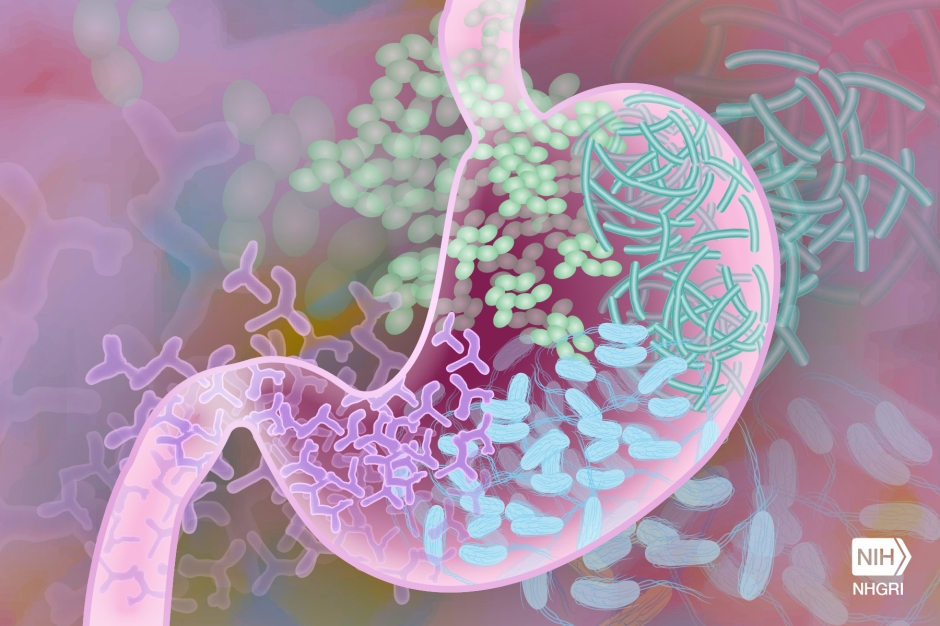

Intestinal landscapes can be categorized into several shapes and sizes. While some are healthy, others are dysbiotic; meaning they do not have what is called a healthy gut microbiome. The latter is a mystery! With more and more research, scientists all over the world are realizing that there is no singular definition or composition of a healthy microbiome. It differs from region to region, diet to diet, person to person and most importantly, it even differs in a person across their lifespan. However, most scientists agree on one fact, a diverse gut microbiome is an essential characteristic of a healthy gut microbiome. But, what else? What else defines a healthy gut microbiome or a dysbiotic gut microbiome?

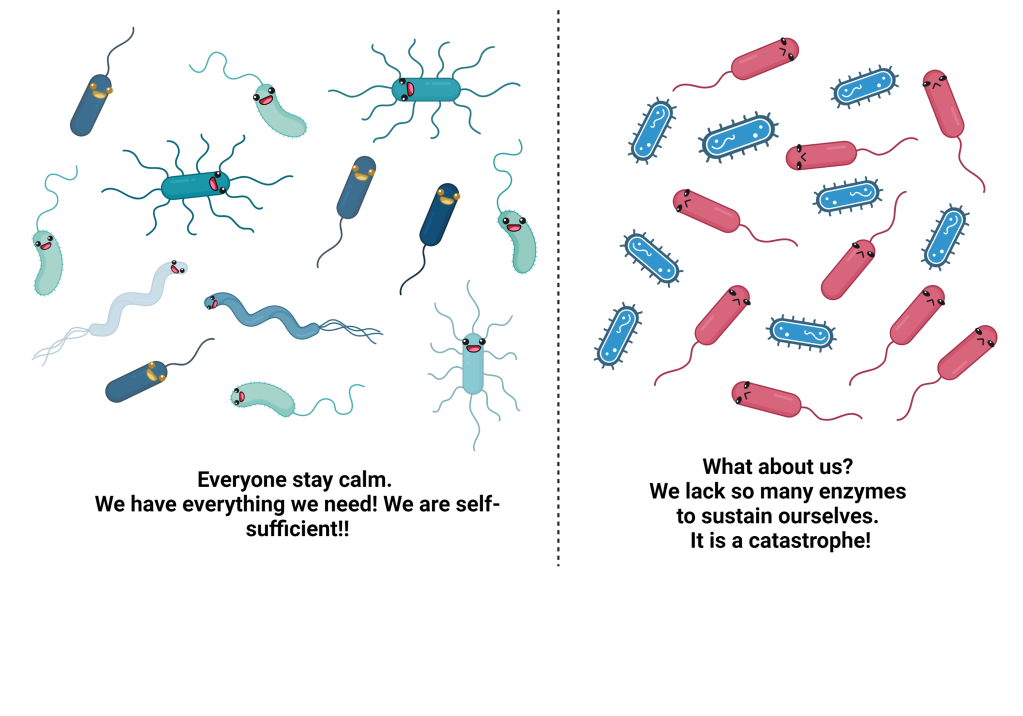

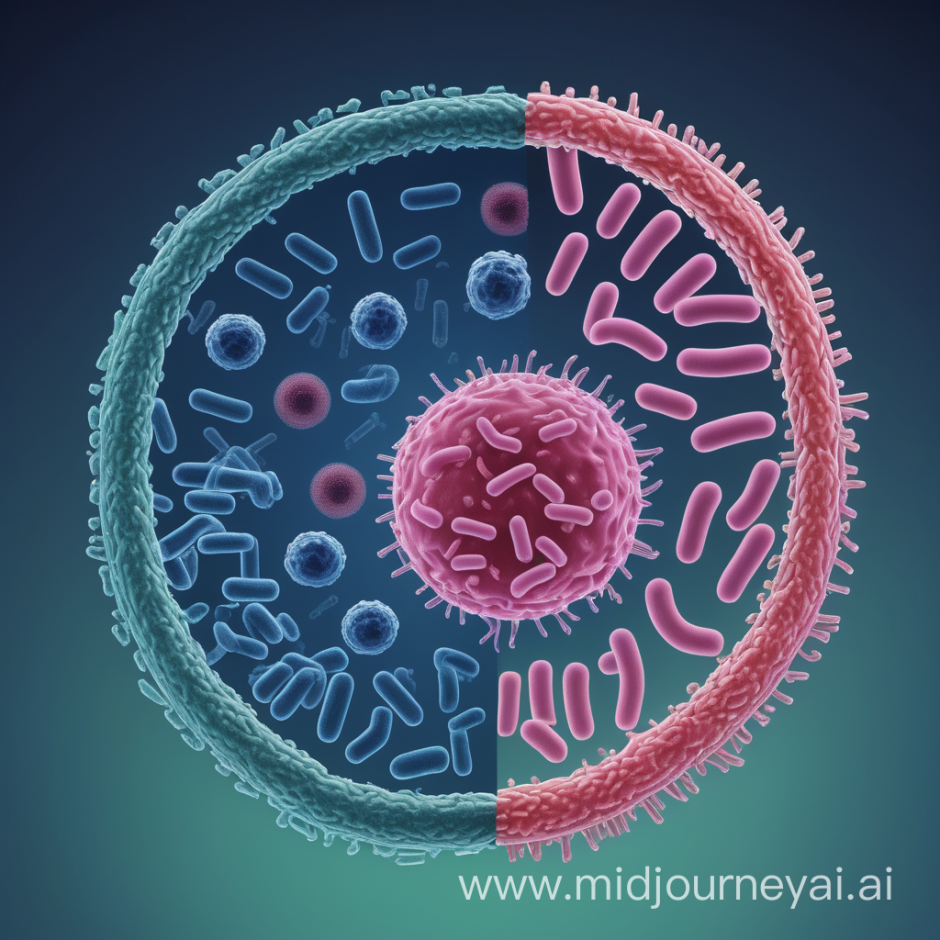

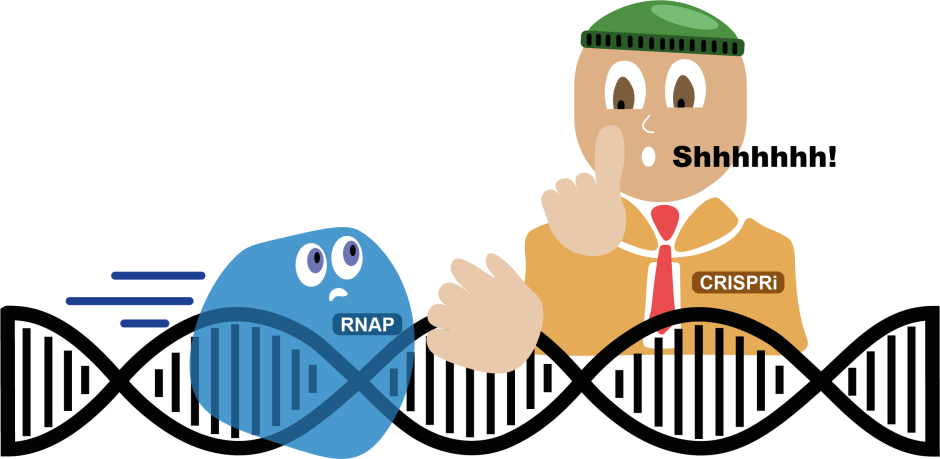

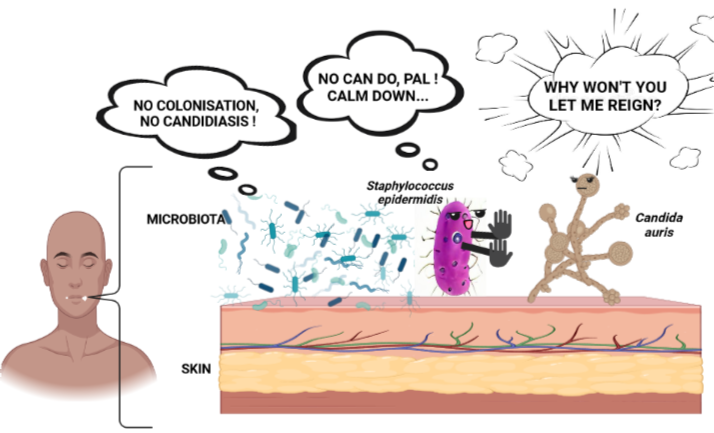

Given the complexity of the gastrointestinal environment and the residing gut microbial community, it becomes difficult to explore how microbes colonize the human gut or how they interact with each other. A research study has shown that a diverse healthy microbial community comprises several auxotrophic microbes which lack genes for synthesizing essential compounds for their survival. However, the auxotrophs are not left alone in their quest. In their vicinity lie some other microbes that can synthesize these essential compounds in excess and can help the auxotrophs survive. In turn, auxotrophs provide other compounds or some other kind of survival advantage. This give-and-take relationship essentially forms the crux of a healthy gut microbial community. This microbial symphony is subject to a healthy gut environment. What happens when the gastrointestinal tract does not provide favorable conditions? The answer to this question is complex.

A stressed gut and its microbiome?

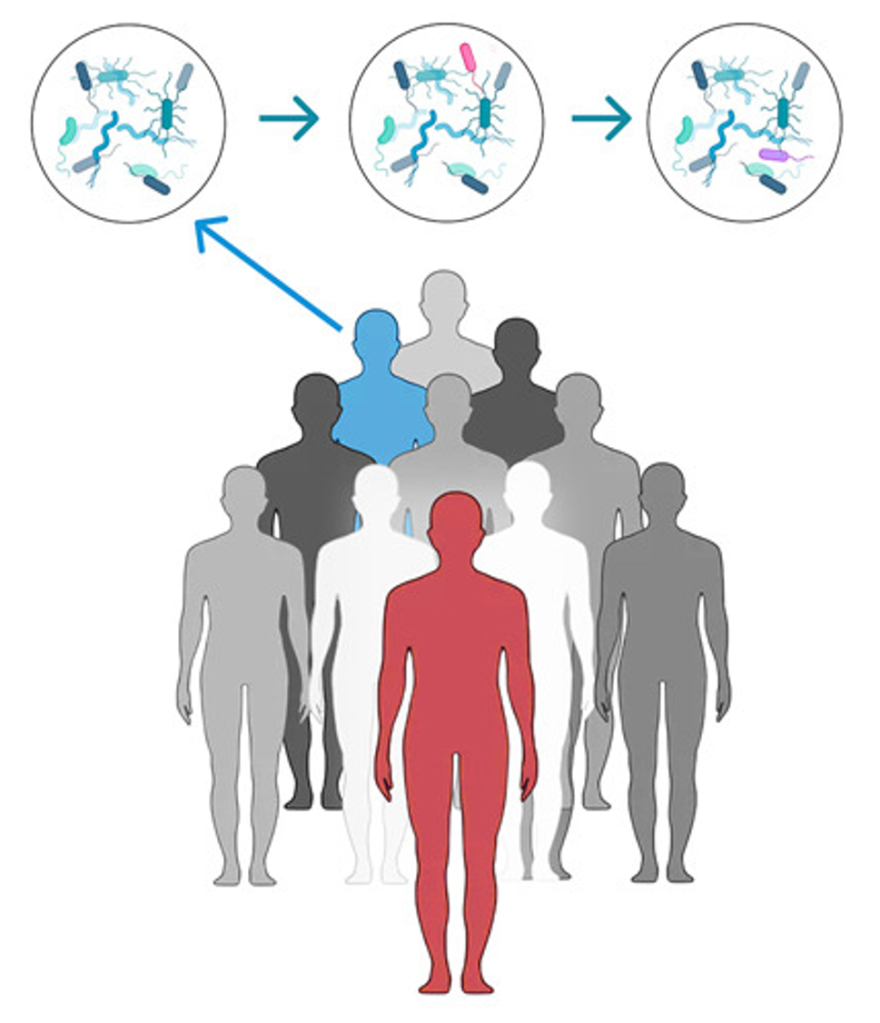

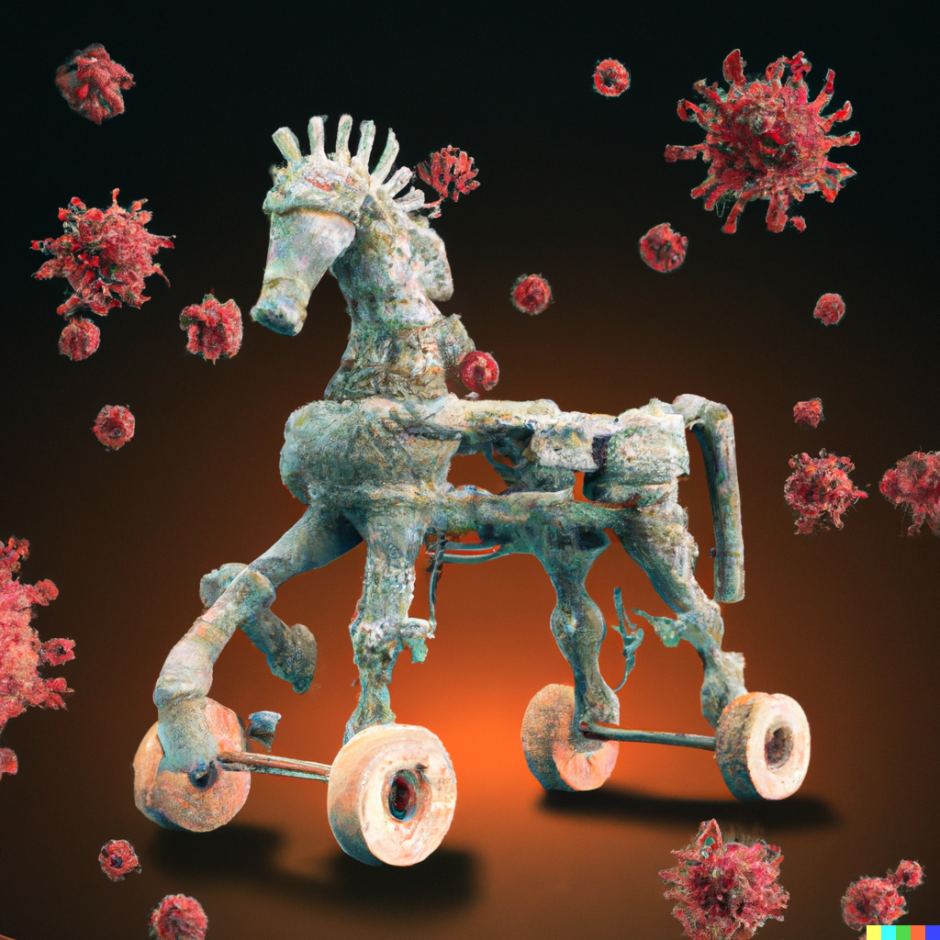

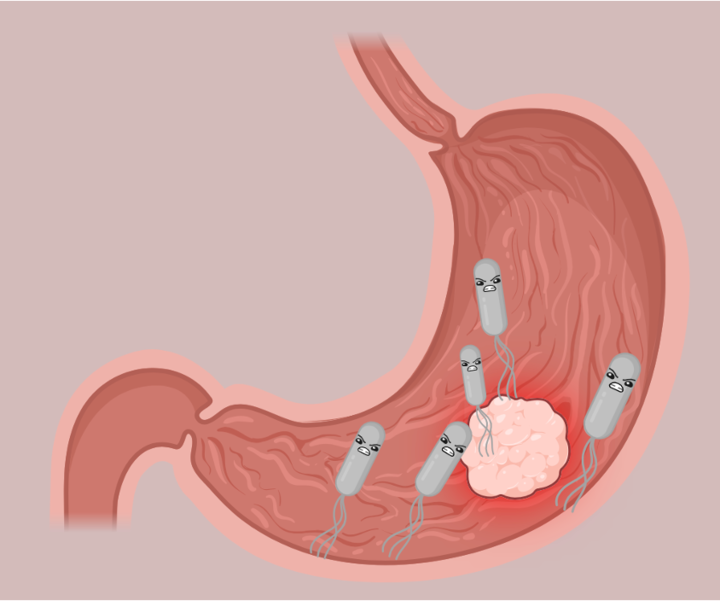

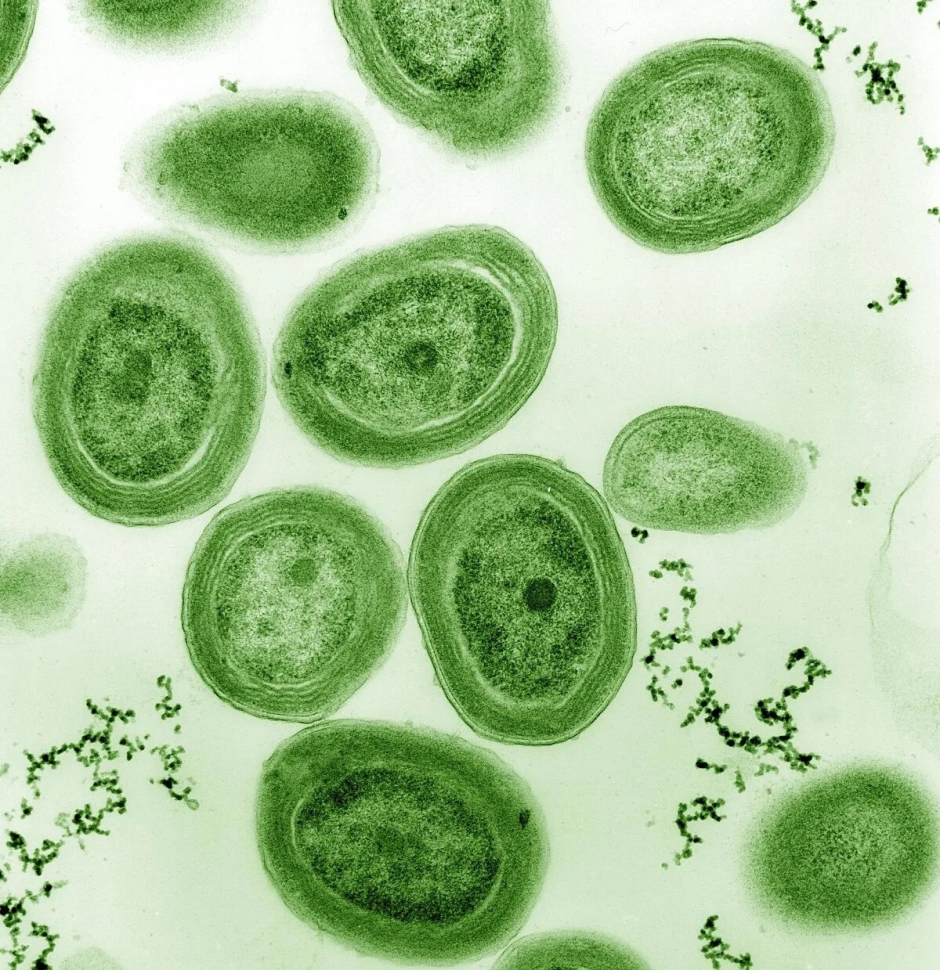

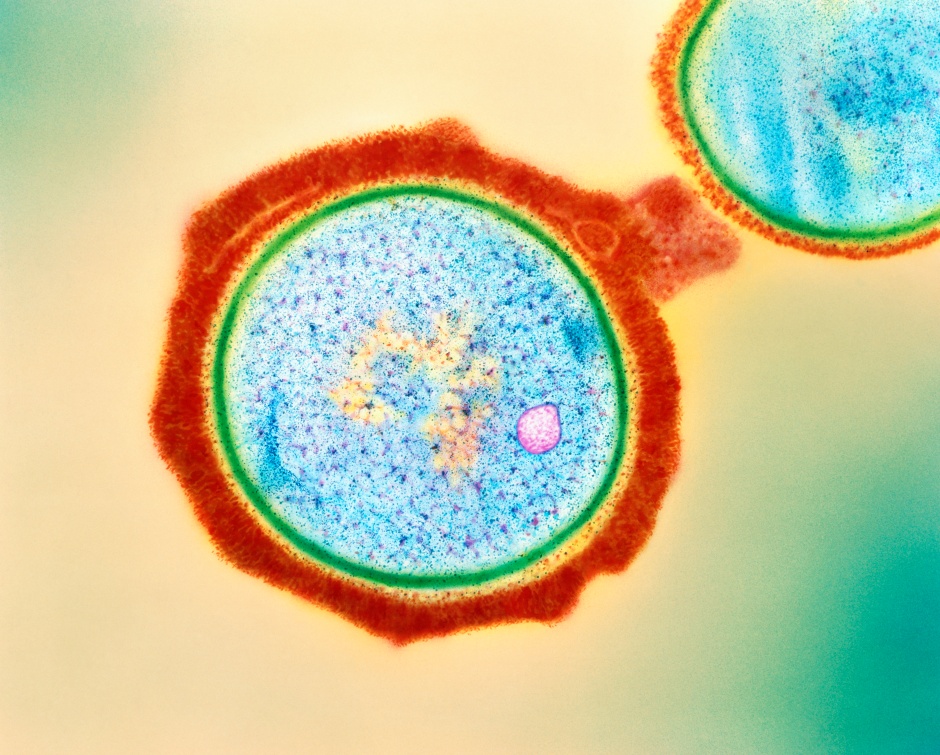

Remember, the ‘nearly’ empty landscape? In case of the intestinal environment, this ‘near’ emptiness can be detrimental. An intestinal environment is healthy if it is not inflamed, leaky nor infected by a pathogen. In absence of these necessary health guidelines, the intestinal environment has an internal lining permeable enough to let opportunistic pathogens in, and cause further chronic or detrimental infection. This layer of complexity in the intestine leads to the establishment of an uneven mix of microbes, which are not necessarily good for gut health. Recently, a group of scientists explored the colonization dynamics of gut microbiota in patients suffering from Clostridioides difficile infection. This type of research is a tricky business! First, these patients had to go through a round of antibiotic treatment to wipe clean their existing dysbiotic gut microbiota. Then, gut microbiota from healthy donors was transferred to the patients’ gut using fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). There are many ways to perform FMT, and in the current study, the scientists used either a capsule or colonoscopy.

After FMT, the scientists compared the microbiota composition between the donors at their baseline and the recipients. They categorized the newly colonizing microbes in the recipients’ gut in two groups: good and poor. They also found that the good colonizers had a relatively more complete metabolic profile, mainly the synthesis of essential organic compounds responsible for general microbial survival. The poor colonizers on the other hand had a reduced metabolic profile.

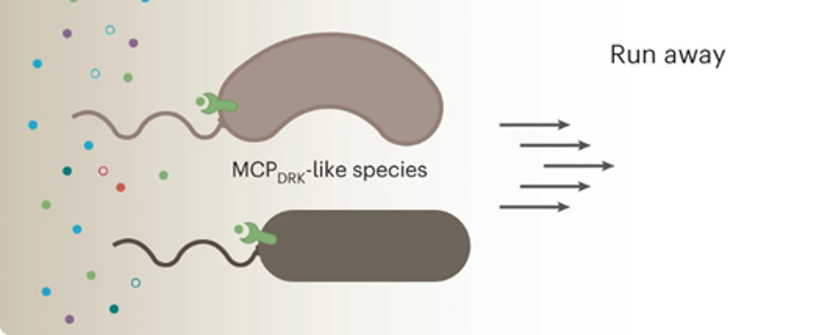

Overall, the scientists deciphered that in a stressed gut environment, microbes that are self-sufficient succeed in establishing their niche. In this case, self-sufficiency refers to the predicted ability of the microbe to synthesize essential organic compounds, cellular building blocks, cofactors, and vitamins for its survival. This, in turn, leads to reduced diversity in the overall gut microbiota, thereby increasing the risk of dysbiosis and pathogenic infection.

What does this mean for the future of FMT?

The study discussed in the article focuses on characterizing the gut microbial community in a stressed gut environment. FMT has proven to be a tool to combat gut microbial dysbiosis in many recent research studies. However, the long-term advantages or disadvantages of this prospective treatment are still being studied and not yet deciphered fully. A couple more years and we may be closer to unraveling the mystery!

Link to the original post: Watson, A.R., Füssel, J., Veseli, I. et al. Metabolic independence drives gut microbial colonization and resilience in health and disease. Genome Biol 24, 78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-023-02924-x

Featured image: By author using Biorender.com