Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Viruses in the gut may be tied to chronic stress

When stress persists long-term, it can have lasting effects on the brain and body. But an organism experiencing stress is not the only one affected. A new study shows how chronic stress can shape the communities of microorganisms that call our bodies home, leading to consequences for immune functioning.

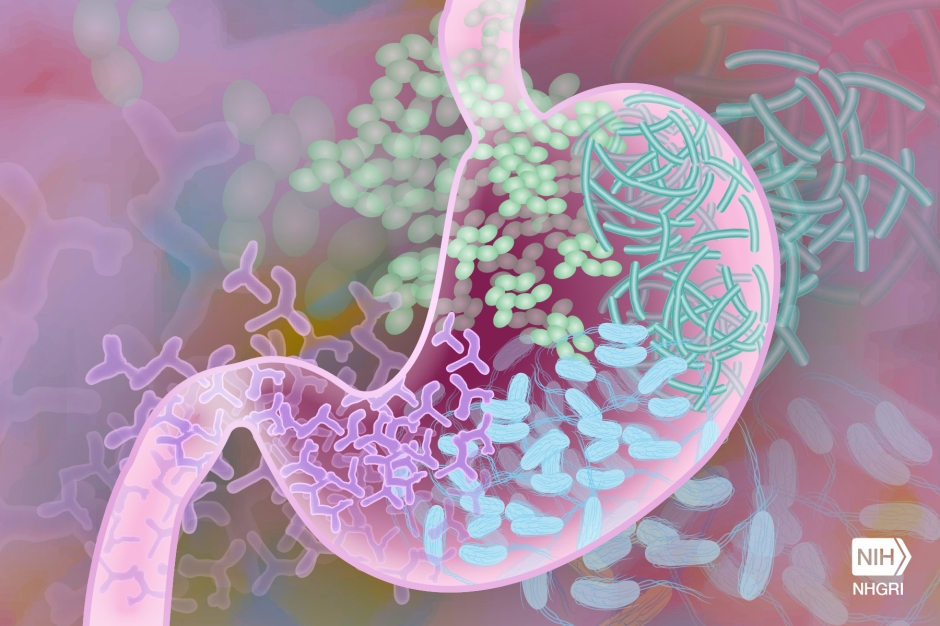

Stress reshapes the gut virome and microbiome

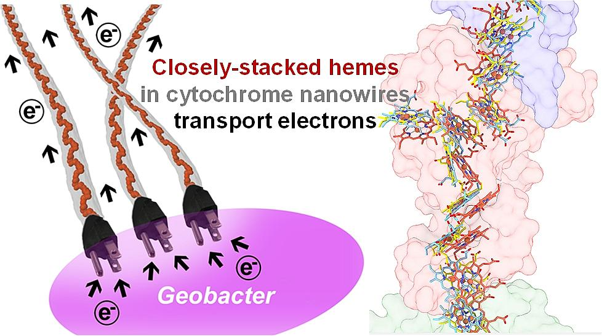

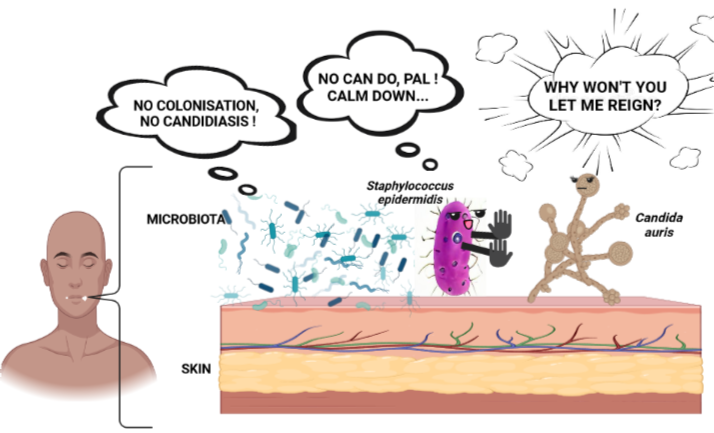

The microbiome refers to communities of microorganisms that inhabit larger organisms. A subset of those microorganisms are viruses that together form the virome. These viruses are specialized to infect, integrate into, hijack or lay dormant in bacteria, and influence which bacteria survive and reproduce.

A growing area of research focuses on the virome, how it shapes the microbiome, how that affects the host, and can be shaped by host factors. Researchers from the University College of Cork in Ireland recently published this study exploring the link between the gut virome and stress in mice.

These authors found that stress can reshape the gut virome, and that altering the virome reduced stress-related behaviors and physiological changes. This means that stress and the gut virome can influence each other.

Exploring the virome in the context of stress

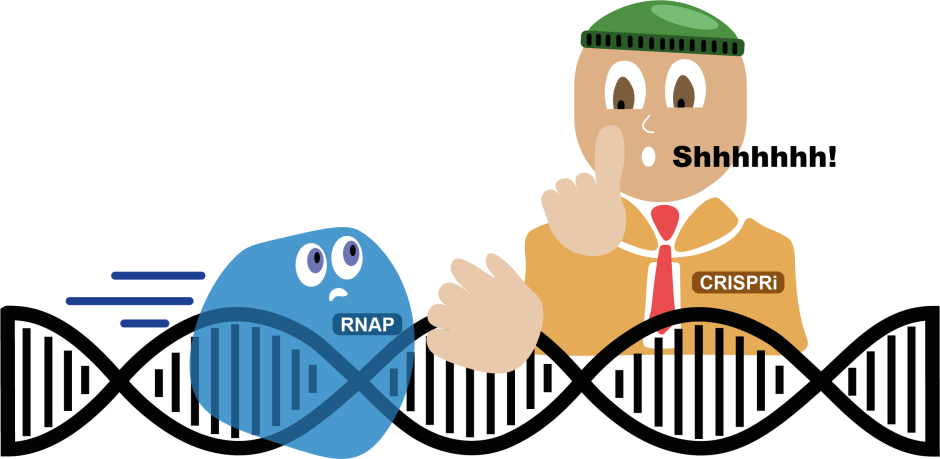

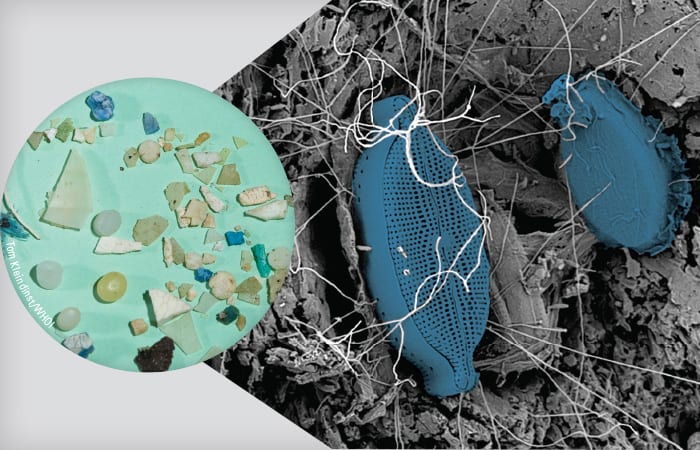

Previous studies that established stress can impact the microbiome have primarily focused on the bacterial species within those microbial communities. But since viruses can reshape these bacterial populations, the researchers of this study wanted to better understand the largely uncharacterized virome because of how these viruses influence the bacterial populations of the microbiome.

To create chronic stress, over the course of 20 days the authors exposed 50 male mice to overcrowding in living spaces and social defeat (losing a fight with a large aggressive mouse). Following this period, they tested the mice for stress-related behaviors, analyzed tissue samples, and collected fecal samples for microbiome analysis. Compared to a control group not subjected to chronic stress, the stressed mice had fewer social interactions, higher levels of stress hormone corticosterone, and increased immune system activation.

Mice under chronic stress also experienced changes in the bacteria found in their fecal samples, and different relative viral quantities in the virome.

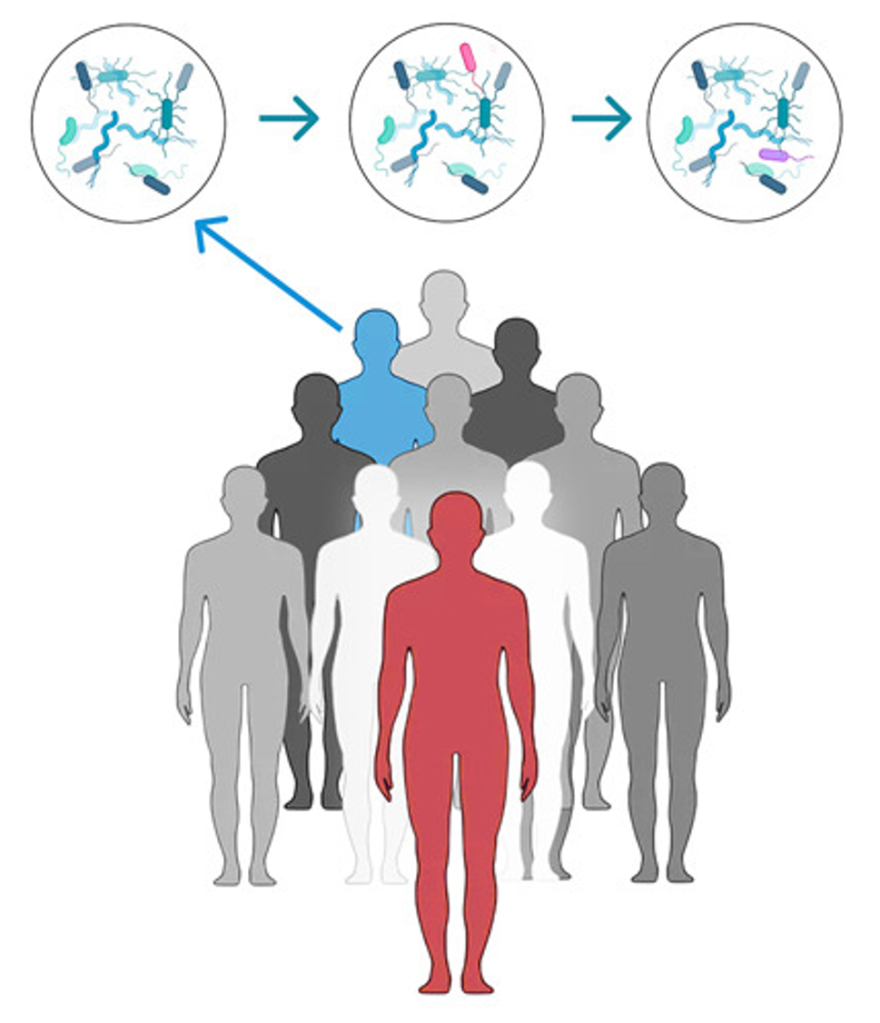

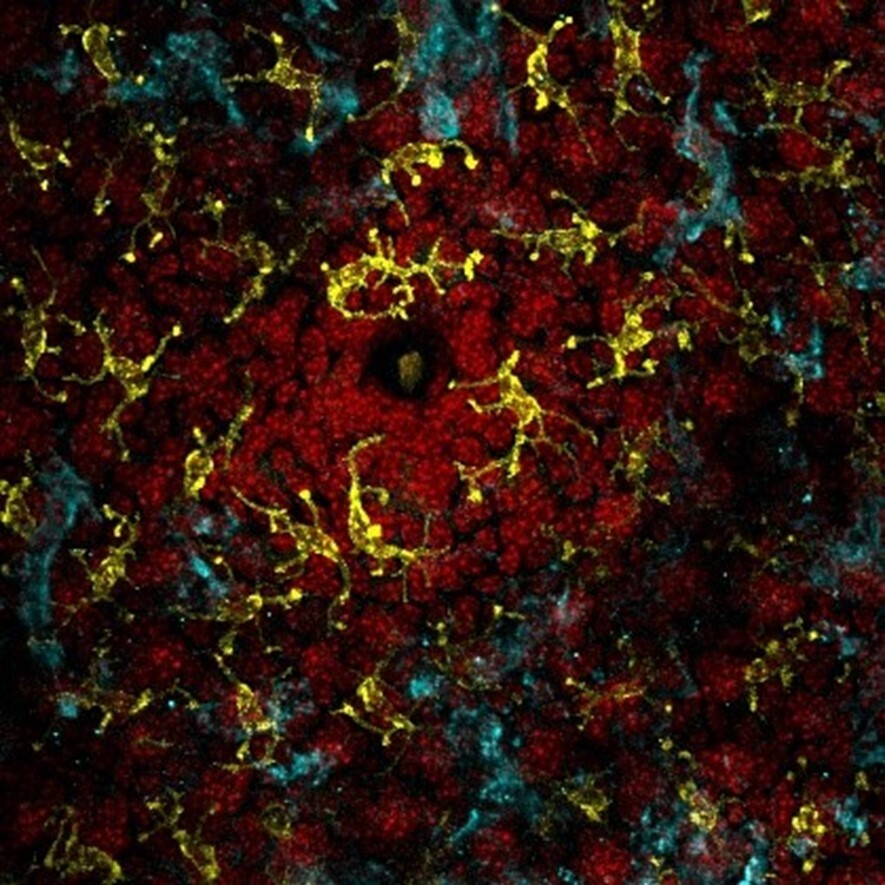

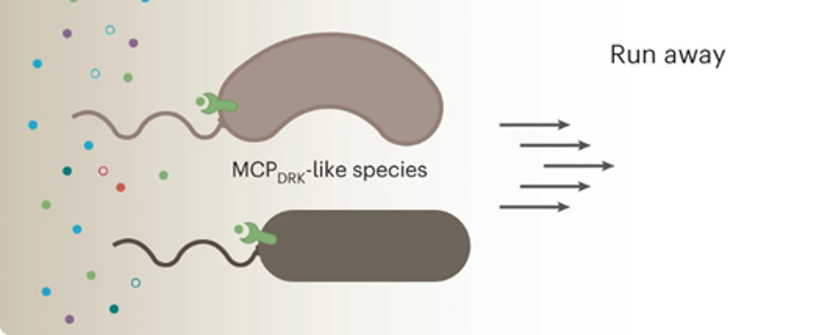

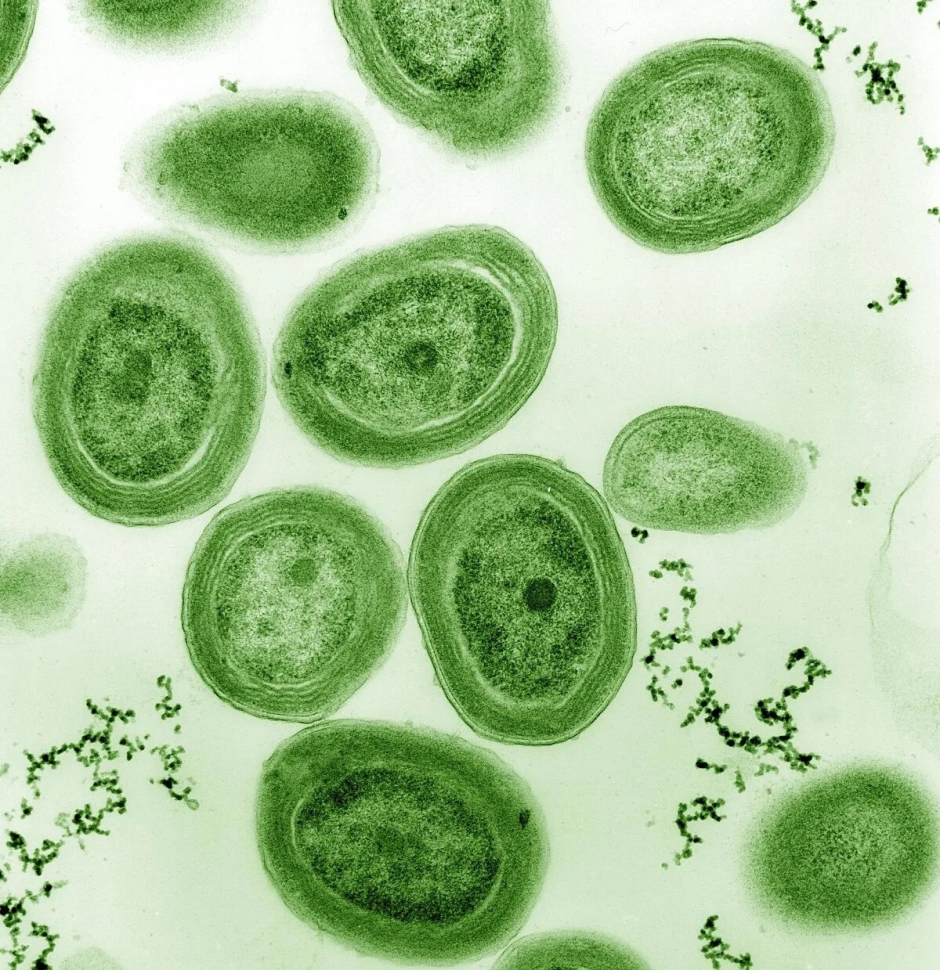

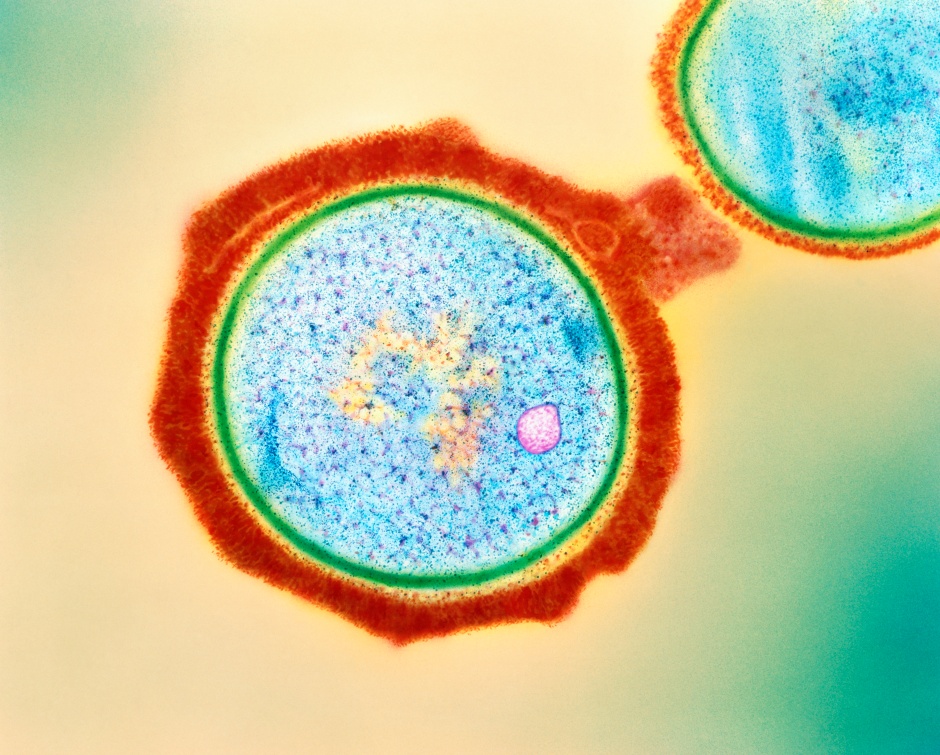

Image source: Nathaniel L. Ritz et al., 2024

Stress and the virome: a two-way street

The researchers also identified several ways in which stress could be curbed through virome-based intervention, or a fecal virome transplant (FVT).

FVTs are isolated samples of the viruses taken from fecal samples, and used to introduce or reintroduce viruses to an organism’s gut microbiome. Here, the authors fed FVTs to the mice throughout the chronic stress period.

The mice receiving FVT while under chronic stress exhibited fewer stress-related behaviors, and reduced stress hormone levels. They also had similar-sized immune cell populations compared to mice not under chronic stress, while the stressed mice with no FVT had reduced immune cell populations.

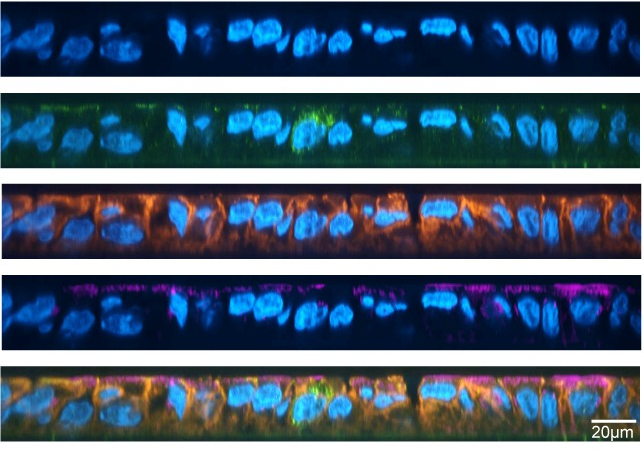

Finally, the researchers compared gene expression in the brain in mice not under chronic stress, under chronic stress, and under chronic stress with FVT intervention. Using RNA sequencing to analyze gene expression, they indeed found that chronic stress modulated the expression of hundreds of genes in these brain regions, but that FVT largely restored expression to levels similar to those of mice not under chronic stress.

The virome reshapes the bacteriome

Having seen how strongly stress can influence physiology and microbiome, the authors turned their attention to how the virome itself changed, and how it reshaped bacterial populations, following FVT.

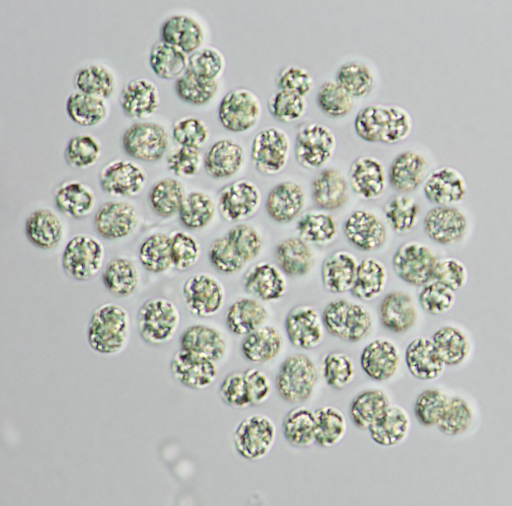

Sequencing the genomes of the microorganisms present in the samples revealed that viruses belonging to Caudoviricetes and Microviridae families dominated the virome, in addition to a substantial number of viruses that have not been categorized in the viral “tree of life”.

Analysis also identified 20 bacterial species that were increased or decreased by stress, but had levels restored by FVT. In particular, bacteria with relatively low abundances changed the most in relative abundance in response to stress and FVT.

What’s next

While this study advanced understanding of how the virome impacts and is impacted by stress, it raises more questions and is not without shortcomings.

Like many mouse studies, only male mice were used. While this practice is common and done for consistency, more could be learned with follow-up studies of female mice.

It is also unclear exactly how stress alters the virome and microbiome, and what the virome and microbiome are doing in the body to protect against the harmful effects of stress.

Overall, this study represents an important step forward in understanding how viruses in the gut and stress affect one another. These findings suggest the virome could be harnessed for therapeutic purposes to combat stress.

Link to the original post: Ritz, N.L., Draper, L.A., Bastiaanssen, T.F.S. et al. The gut virome is associated with stress-induced changes in behavior and immune responses in mice. Nat Microbiol 9, 359–376 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01564-y

Featured image: Bing Image Creator