Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Do Spiny Lobsters Stand a Chance Against Predators?

Oh, the duality of parasites. While some can certainly be helpful, others may enter the wrong host and cause a wide range of issues. From seemingly minor changes to metabolites of the parasitic host to major changes like outward appearance of the host, parasites can affect their host species in numerous ways.

The Parasite and the Host

Fourzán and her team sought to characterize one of these host-parasite relationships by examining infections of the Caribbean spiny lobster, Panulirus argus, by the parasite Cymatocarpus solearis. C. solearis is a type of flatworm that uses the spiny lobster as one of its second intermediate hosts in its life cycle. Infection of the secondary host occurs when the cercariae, the free-swimming larval stage of the parasite, penetrate the lobster’s body and migrate to the tissue where they encyst.

For commercially valuable lobsters like the spiny lobster, fisheries are impacted if these parasites were to increase the lobster’s susceptibility to predation. If lobsters infected with these parasites are more susceptible to predation then these fisheries stand to suffer financial setbacks as the numbers of lobsters available to them might be decreased from increased predation. To determine if these fishing cooperatives should be concerned, researchers in this study set out to discover how these parasites were impacting the spiny lobster’s ability to avoid predation by looking at different biochemical processes as well as behavioral modifications.

Where?

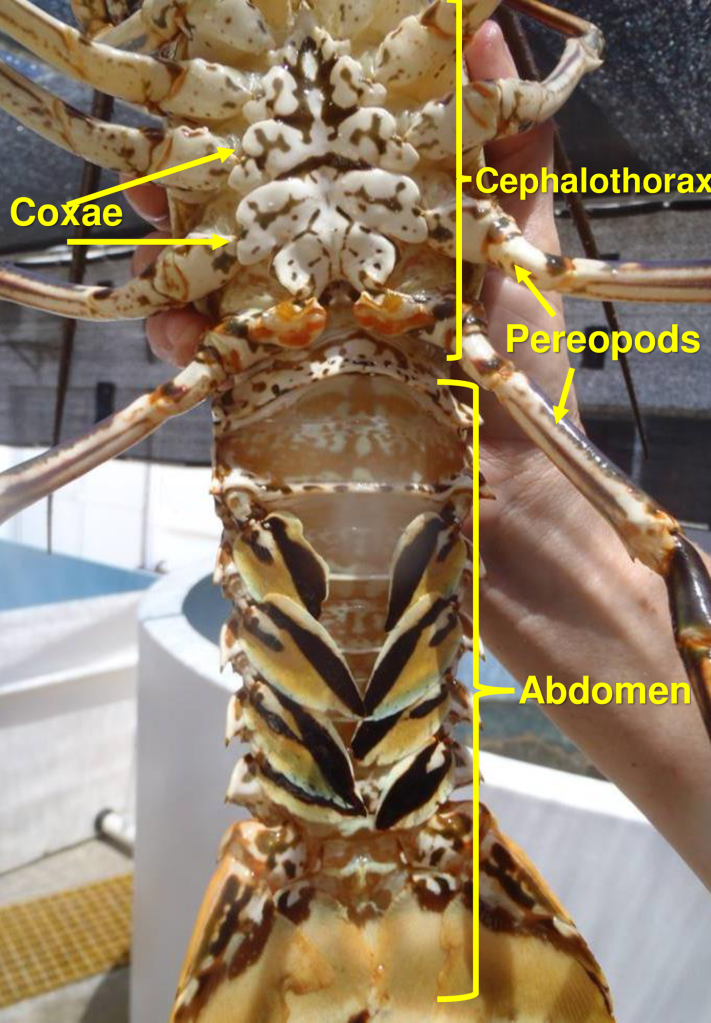

Infection of the spiny lobster by C. solearis was first discovered at Bahía de la Ascensión, a large bay on the Mexican Caribbean coast where a successful fishery for spiny lobsters is located. The cysts of C. solearis appear whitish and spherical ~1 mm in diameter and are visible to the naked eye in the abdominal muscles of the lobster.

Rapid field surveys, based on this visual assessment, approximated the prevalence of infection at about 14% in 2016. However upon dissection of the lobster, the cysts were also present in the muscles of the cephalothorax and coxaethan, indicating that visual assessment may underestimate the true prevalence of infection (Figure 2).

On to the Experiments

To set up these experiments, researchers purchased live, legal sized lobsters from fishing cooperatives from Bahía de la Ascensión and Bahía Espíritu Santo, both of which are on the Caribbean coast of Mexico. The lobsters were divided into 4 groups based on the number of cysts (metacercariae) of C. solearis identified by visual inspection in the muscle tissue of the abdomen. Groups were divided as follows: Uninfected (0 metacercariae), Lightly Infected (1-10 metacercariae), Moderately Infected (11-30 metacercariae) and Heavily Infected ( >30 metacercariae).

The Swim Escape

One important experiment the researchers ran was looking at the swim performance of lobsters which also indicates their escape response. To conduct these experiments, the scientists used a concrete channel with a partition to keep the lobsters in the start zone. After introducing the lobster to the channel, a person would rapidly place their hands in the channel to simulate a predator attack while the partition was lifted allowing the lobster to swim backwards. Researchers measured 6 variables including: (1) delay (s) to escape, (2) duration of a swimming bout (s), (3) distance (m) traveled in a swimming bout, (4) overall swimming velocity, (5) acceleration and (6) force exerted. Surprisingly, the presence and intensity of the parasite had no significant effects on any of these response variables.

Non-Significant Results

Other experiments looked at the growth rate of lobsters, concentrations of albumin, cholesterol, and total protein in plasma of individual lobsters and the concentration of dopamine (DA) in the plasma, all of which there were no significant differences between the groups.

Glucose and Serotonin

Levels of one metabolite and one neurotransmitter did show significant differences, however. The concentration of glucose in the heavily infected lobsters was significantly lower when compared to the lobsters with a light or moderate infection. In addition, the hemolymph (fluid in invertebrates equivalent to blood in vertebrates) contained a higher concentration of serotonin (5-HT, a neurotransmitter regulating numerous bodily functions/processes) within the heavily and moderately infected lobsters as compared to the lightly and uninfected lobsters.

So, Does the Parasite Affect the Lobster or Not?

Studies have shown that 5-HT may exert different effects on glucose metabolism albeit species dependent. 5-HT may cause these heavily infected lobsters to become more aggressive and fight off attackers beyond their capabilities. Despite no differences in the escape response test the lower amount of glucose in the hemolymph for heavily infected lobsters combined with a lower glucose may cause lobsters that stand their ground and fight to have reduced capabilities/energy availability to fight off predators. However, this is all speculative and additional studies looking at defense and antipredator behaviors in uninfected and infected lobsters should be conducted in the future.

Featured image: Spiny lobster climbing over rocks. Credit: 4726344 © Steve Kim | Dreamstime.com