Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Zika Viruses’ Unlikely Friend

What is Zika virus?

Zika became a household name in 2015 when large outbreaks began across the Americas. In just seven months, from February to April of 2015, 7000 cases of illness and skin rash were reported in Brazil; these cases were later connected to Zika virus. Following the Zika outbreak, an unprecedented number of babies were born with microcephaly – a condition where an infant’s head is smaller than normal. Microcephaly can cause developmental complications and seizures. Newborn complications are thought to be partially a result of vertical transmission of the virus from the mother to the fetus – when the virus is passed from the mother to the fetus during pregnancy. However, recent research has suggested that having immunity against dengue virus may exacerbate Zika virus infection, especially during pregnancy.

Zika and Dengue – Unfortunate Relatives

Zika and dengue viruses are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, meaning they are often found in the same place. Dengue is another mosquito-borne virus closely related to Zika that can cause flu-like symptoms and, in rare cases, is fatal. Due to the co-circulation of these viruses, occasionally, a person might be unlucky enough to be infected with both. Previous research has shown that dengue immune serum, which is a plasma that contains antibodies to fight dengue infection, worsens Zika in human white blood cells and pregnant mice. Interestingly, other studies have shown that prior dengue infection does not affect Zika virus in non-pregnant animals. So, something about pregnancy specifically causes an unusual interaction between previous dengue infections and current Zika infections – but why?

Not All Antibodies are Good

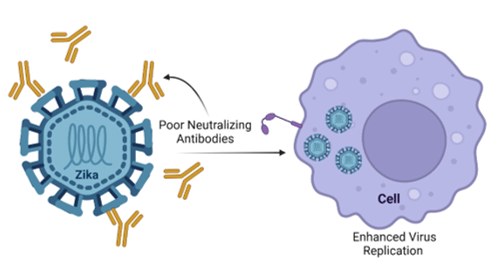

Model of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement. Made with Biorender.com

A possible explanation could be due to something called antibody-dependent enhancement. Antibody-dependent enhancement occurs when antibodies, which are supposed to help fight off infections, actually increase virus entry into the cell. Typically, antibodies will bind to a pathogen and prevent the pathogen from entering and replicating within the cell. However, on rare occasions, the antibody can act as a trojan horse enabling pathogens to infiltrate the cell, where they can replicate. This phenomenon is more typical with dengue virus.

Dengue virus has something that makes it more unusual than other viruses: it has four different forms. When a person is infected with one form of dengue virus, they usually have mild symptoms, if they have any symptoms at all. However, if that person later in life is infected with a second form of dengue virus, they are more likely to develop severe symptoms – this is because the antibodies the person made during the first infection were good at fighting off that infection, but now these antibodies recognize the new form of virus and instead facilitate infection.

But how does antibody-dependent enhancement relate to Zika virus and pregnancy? During pregnancy, tissues like the placenta are protected from normal immune responses like inflammation to keep the baby safe. Zika might be exploiting this, and along with a possible antibody-dependent enhancement attributed to prior dengue infection, it could result in disastrous consequences for the fetus.

The Findings

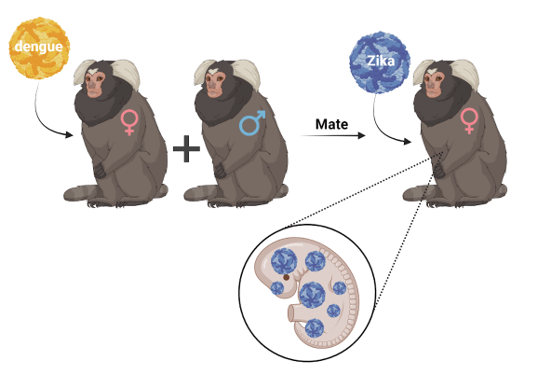

Researchers at the Trudeau Institute aimed to determine the impact of dengue infection on Zika infection in pregnant marmosets. Marmosets are non-human primates that are immunologically similar to humans, which, in this case, makes them the ideal test subjects.

Before moving to an animal model, they first explored the impact of dengue immune serum on human white blood cells infected with the Zika virus but saw no effect. This means that in the hands of these researchers, the presence of dengue antibodies in human white blood cells does not worsen Zika infection. However, the researchers used dengue antibodies produced in marmosets, which may not work the same in human cells. To confront this problem, they again used dengue immune serum from marmosets, but this time, in cells from marmosets. When these cells were infected with Zika virus, they saw a worse Zika infection than in cells not treated with the dengue immune serum.

Now that the researchers had looked at the effect of dengue infection on Zika infection in cell culture, they next wanted to move to their marmoset animal model. They mated dengue-immune female marmosets, which had anti-dengue antibodies, with male marmosets. Once pregnancy was confirmed, they infected these females with Zika virus. The researchers saw that in the marmosets that were immune to the dengue virus, there was a greater increase in Zika in the placentas, the organ responsible for delivering nutrients to the fetus. The fetuses themselves also showed high levels of Zika virus.

Zika virus proteins were also found in fetuses with dengue-immune mothers – the researchers saw Zika virus proteins in the fetus’s brain, which could cause neurological damage. However, when they looked at the saliva and urine of the female marmosets, they did not see a significant increase in Zika virus, showing that dengue immunity was specifically affecting the fetus. This research supports that prior dengue infection worsens Zika virus infection in fetuses. But is this due to antibody-dependent enhancement? The short answer is that we still do not know.

While the researchers did find that the dengue-immune marmosets had antibodies that would bind Zika virus and that they were poorly neutralizing, meaning the antibodies were unable to stop the virus, they also saw that after some time, the amount of Zika virus-neutralizing antibodies was comparable between marmosets that had dengue immunity and marmosets that did not. This indicates both marmosets should be able to fight off Zika infection. While this research does not conclusively suggest that antibody-dependent enhancement is responsible for dengue immunity making Zika infections worse in fetuses, it does not rule it out.

What does this mean?

While the findings of this research are not good news – it does give future research directions that could someday prevent Zika infection in fetuses. It also is a reminder that contracting a mosquito-borne pathogen can have serious consequences, so make sure to do everything you can to prevent getting bitten.

Link to the original post: Impact of prior dengue virus infection on Zika virus infection during pregnancy in marmosets. (Kim IJ, Tighe MP, Clark MJ, Gromowski GD, Lanthier PA, Travis KL, Bernacki DT, Cookenham TS, Lanzer KG, Szaba FM, Tamhankar MA, Ross CN, Tardif SD, Layne-Colon D, Dick EJ Jr, Gonzalez O, Giraldo Giraldo MI, Patterson JL, Blackman MA. Impact of prior dengue virus infection on Zika virus infection during pregnancy in marmosets. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jun 7;15(699):eabq6517. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq6517. Epub 2023 Jun 7. PMID: 37285402.)

Featured image: Created by author with Biorender.com