Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Cool Fungi

Fungi are incredible organisms that play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of our planet. They break down decaying matter and provide essential nutrients for new growth. They come in different forms, from mushrooms to tiny molds and yeasts, and can be helpful for food and medicine. However, some can harm plants and animals as well.

Scientists are still uncovering the secrets of how fungi respond to temperature, which is particularly important in the face of global warming. Previous studies have shown that mushrooms grown in labs are inherently colder than their surroundings, which helps with spore dispersal. Recent observations confirm that wild mushrooms also appear relatively cold.

Temperature affects all living things. If an organism gains more heat than it loses, it gets warmer, and vice versa. Organisms can have different temperatures from their environment. Some animals like birds and mammals can control their body temperature (because they are warm-blooded), while most other life forms, like reptiles (cold-blooded) and plants, depend on the temperature of their environment. These organisms use other methods like sweating and evaporation of water to cool themselves down. But what about simpler organisms like fungi?

A study performed by Cordero and colleagues used special tools to measure the temperature of wild mushrooms and lab-grown fungi. They found that these mushrooms and fungi are colder than their surroundings and release heat through evaporation.

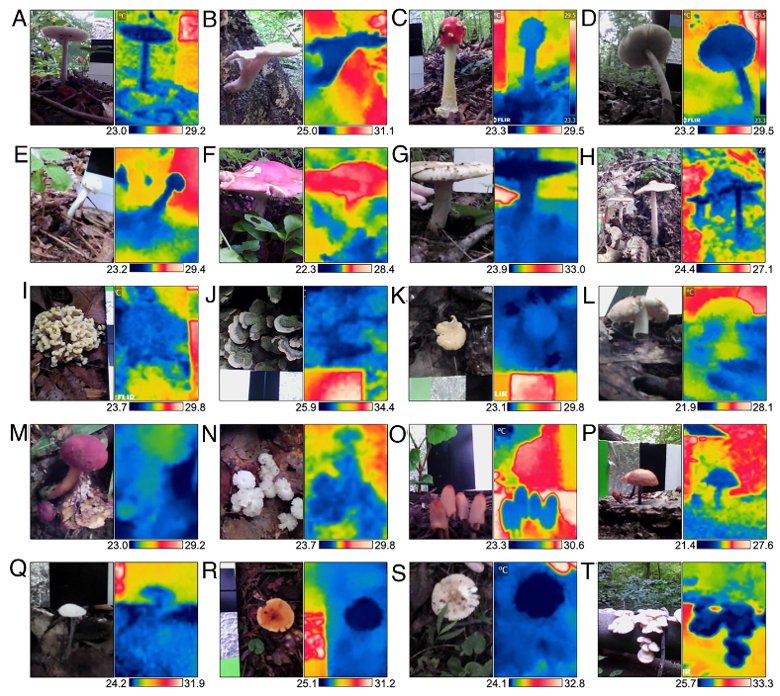

By imaging 20 wild mushroom species with an infrared camera, they found that the mushrooms were 1.4 – 6°C colder than their surroundings. Depending on the kind of mushroom, their capacities to cool down varied. This could be likely due to size, color, habitat lifestyle etc…

Another example is the commonly used Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). Even when grown in the lab at 25 °C, and separated from its substrate (the food source it is growing on), it maintains its temperature throughout its growth. Heating and cooling experiments showed that different parts of the mushroom release heat differently: The temperature changes followed different patterns during heating and cooling. The mushroom exhibits different heat release patterns during heating and cooling, indicating its unique ability to regulate temperature.

When studying other mushrooms in the lab, such as the Champignon (Agaricus bisporus), the researchers saw that the mushrooms have the ability to cool themselves through evaporative cooling. When the mushrooms were dehydrated, they couldn’t maintain cooler temperatures. Similar evaporative cooling was observed in other fungi like the pathogenic yeast-like Cryptococcus neoformans and food-spoiling Penicillium. Water droplets formed on the lids of the petri-dish above these fungal colonies, and areas without fungal growth had less condensation. The findings confirm that evaporative cooling is a mechanism used by mushrooms and other fungi to regulate their temperature.

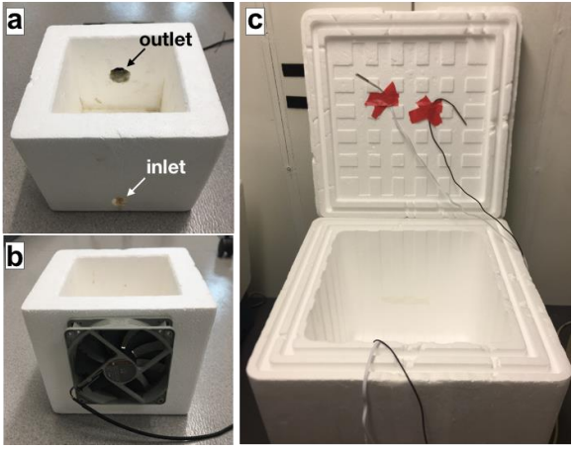

In addition to all the research done on the cooling mechanisms of fungi, the researchers created a device called MycoCooler™. The device was made from a box with openings for air to flow in and out, and it was loaded with substrate-detached Agaricus bisporus mushrooms. When placed inside a warm room, the temperature inside the box decreased by 10 °C in 40 minutes! Comparing the cooling capacity to water alone, a single mushroom was 12.5% more effective at cooling the air compared to an equivalent mass of water. Other substances like ethanol, phosphate saline buffer, and Coca-Cola were less effective than the mushroom.

Having a cold surface on mushrooms is important for releasing spores. Spore discharge happens when tiny drops of water condense on the spore surface, causing them to detach and be released into the air. Colder temperatures also affect spore formation in fungi. For example, in certain fungi, spore production occurs at colder temperatures compared to their surroundings. This is also observed in sperm production in mammals. The relationship between colder temperatures and spore production suggests that being cold helps fungi produce and release more spores. The cold temperature of mushrooms may also attract insects, aiding in spore dispersal.

As fungi are actually colder compared to their surroundings, this “fungal hypothermia” means that they lose more heat than they produce. It’s like they become a sort of heat sink, absorbing thermal energy from their environment. This cooling ability is important for fungi to maintain their temperature balance and adapt to different conditions. This is important as fungi face challenges from climate change and the emergence of new pathogenic species.

Interested in other exciting properties of fungi? In this article, we highlight the conductivity of fungal filamentous strands and the function they could have in electronics!

Link to the original post: Radames J. B. Cordero, Ellie Rose Mattoon, Zulymar Ramos, and Arturo Casadeval. The hypothermic nature of fungi. PNAS, May 2, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2221996120

Featured image: Created with DallE

Image 2 sources: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pleurotus_ostreatus_-_Pleurote_en_hu%C3%AEtre.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-02-12_Agaricus_bisporus_%28J.E._Lange%29_Imbach_403678.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cryptococcus_neoformans_,capsul,India_ink.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Penicillium_italicum_sur_Cl%C3%A9mentine.JPG