Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Anorexia: could the gut-brain axis play a role?

Eating disorders such as anorexia are gaining more exposure in this age of social media. Young women, who tend to be the face of disordered eating, are more comfortable sharing personal battles with anorexia, binge eating, etc., to show others the many faces that such a disorder can take. From exposing “almond moms” who brag about only eating an almond for breakfast to the widely reported usage of the diabetes medication Ozempic among a variety of celebrities, confirmed and unconfirmed, for weight loss purposes, the politics around body image issues is coming sharply into focus. Yet, scientific understanding of the pathogenesis of eating disorders such as anorexia is still lacking.

What exactly is anorexia?

Pathogenesis aside, what exactly is anorexia? The disorder is characterised by a series of symptoms. These symptoms include reduced food intake, increased physical activity, and obsessive thinking around food such as counting calories and religiously checking one’s weight to gauge changes, as well as a generalised emotional rigidity also known as anhedonia.

The physical outcomes of these behavioral changes can be drastic, ranging from fatigue and dizziness to severe hair loss and teeth erosion. It is easy to see how this disorder has such a low percentage of remission given the circular nature of body dysmorphia this disorder can lead to: one feels poorly about their weight and appearance, leading to reduced food intake and increased activity, which then leads to worsening perception of their body due to the worsening physical symptoms…continuing the vicious cycle.

The “omics” approach

Let’s take a quick aside from anorexia to talk about the gut-bacteria brain axis and the rise of metagenomics and metabolomics in current research. It has long been understood that what you eat affects your physical health, but did you know that it can also affect your mental health? The human digestive tract contains microorganisms that “eat” what you do, and their by-products can often mimic human proteins and have been shown to tune chemical signals to the brain!

The gut-bacteria-brain axis is the crosstalk between these different elements of our bodies. To better study this axis, scientists have been using metagenomics and metabolomics, the study of the different bacterial communities colonizing a certain body part, and the study of the metabolites existing in our bodies at any given time, respectively. Metabolomics and metagenomics are part of the “omics” revolution of the 2010s, which broadly involves studying genes and their expression via machines that can sequence large numbers of nucleic acids from cellular or tissue samples with high accuracy and depth.

Gut-microbiota-brain axis and anorexia…what do we know?

So, bringing our focus back to anorexia, three scientists across the EU decided to uncover the impact of anorexia on the gut-bacteria-brain axis using an “omics” approach. Drs. Yong Fan, René Klinkby Støving, and Samar Berreira Ibraim collected human fecal samples from women affected by anorexia (AN) or not affected (healthy-weight), choosing to examine women specifically as 95% of AN cases tend to be in young women. DNA extracted from these samples were sequenced and the “reads” were aligned to pre-existing maps of gut genes.

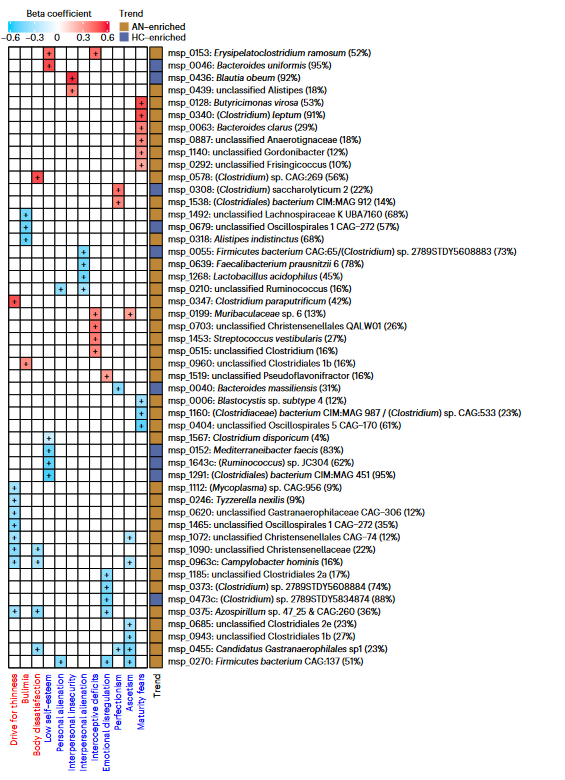

The scientists discovered that there was variation in the genre of bacteria that existed in the AN gut versus the healthy-weight gut. Along with collecting their fecal samples, the scientists also distributed a standard anorexia questionnaire called the Eating Disorder Inventory 3 (EDI-3) to the AN group to assess eating behavior, with criteria such as “personal alienation” and “drive for thinness” to derive a score for disorder severity.

Scores on the questionnaire were then matched to bacterial populations – for example, Clostridium was positively correlated to high AN scores, and the abundance of Parasutterella correlated with “body dissatisfaction.” At the species level, the AN gut bacteria had higher beta-diversity, pointing to a greater level of variation within the colonising bacteria species. Viruses were also accounted for in this study – observing higher viral diversity and richness in the AN samples. Interestingly, the phages infecting Lactococcus lactis were enriched in the AN samples, whose bacterial hosts are used to make fermented foods. They also observed that virus-bacterial host interactions decreased in the AN fecal samples post bulk RNA sequencing, specifically with bacteria made by the main gut metabolites known as short-chain fatty acids, via a statistical method called Principal Coordinate Analysis.

At this point, the researchers had an idea of what made up the bacterial and viral communities of the guts in their anorexic cohort, but what about the “brain” component of the gut-microbiota-brain axis? Using the pre-established Gut Brain Modules, a database that had a repository of data on neuropeptides and hormones that affected/were affected by gut microbiota, they predicted several modules that could affect the anorexic gut. For example, dopamine, which is known to affect mood and appetite, was decreased in the case of the AN samples, but serotonin biosynthesis was enriched in the samples. Though, as with most neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin are complex players that are finely tuned to physical states of being and the behavioral outcome we see as a result are hard to discern to simple ‘upregulation/downregulation’ dichotomies.

Of course, predictive modules based on questionnaires and fecal samples did not allow the scientists to see a clear cause-and-effect due to the many factors that play into human habits that cannot be controlled for! To get around this issue scientists often use mouse models, which is exactly what they did in this study. To observe a causal relationship between the anorexic gut microbiota and disease phenotype, they transplanted the previously mentioned fecal samples into germ-free (meaning they did not have a microbiota) mice, from both the AN and healthy-weight cohorts. They observed that the mice that had the AN transplantation had a greater decrease in body weight and slower weight gain compared to the mice that had the healthy-weight transplantation! To once again add a “brain” component, the hypothalamus of the mice (the brain region known to play a role in appetite regulation) was examined – and unsurprisingly there was a difference in gene expression between the two groups of mice. The AN mice had a higher expression of genes that are known to suppress appetite. They also had highly expressive thermogenesis genes in their fatty tissue, which are genes that impact energy storage and metabolism when other sources of energy are already depleted.

A clearer idea of how gut dysregulation affects anorexia pathogenesis

The study conducted was certainly ambitious. Teasing apart a complex system such as the gut-microbiota-brain axis in the context of anorexia was no easy feat, and there were many interesting takeaways. For one, the bacteria and viruses that exist in the anorexic gut differ from those in the healthy gut, leading to the question of how exactly does the change in community diversity occur?

Next, we now know the exact bacterial and viral species colonizing the unhealthy gut in the context of anorexia, perhaps opening the door to creating therapies that can reverse their state to that of a healthy gut. Even with certain limitations such as a smaller cohort size limited to people of one country, the scientists were able to use a predictive algorithmic approach along with a mouse model to better understand the relationship between bacterial communities in guns and chemicals in the brain that lead to the symptoms doctors across the world characterize anorexia by.

Link to the original post: Fan, Y., Støving, R.K., Berreira Ibraim, S. et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa in humans and mice. Nat Microbiol 8, 787–802 (2023).