Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

CRISPRi: a DNA silencer worth making noise about

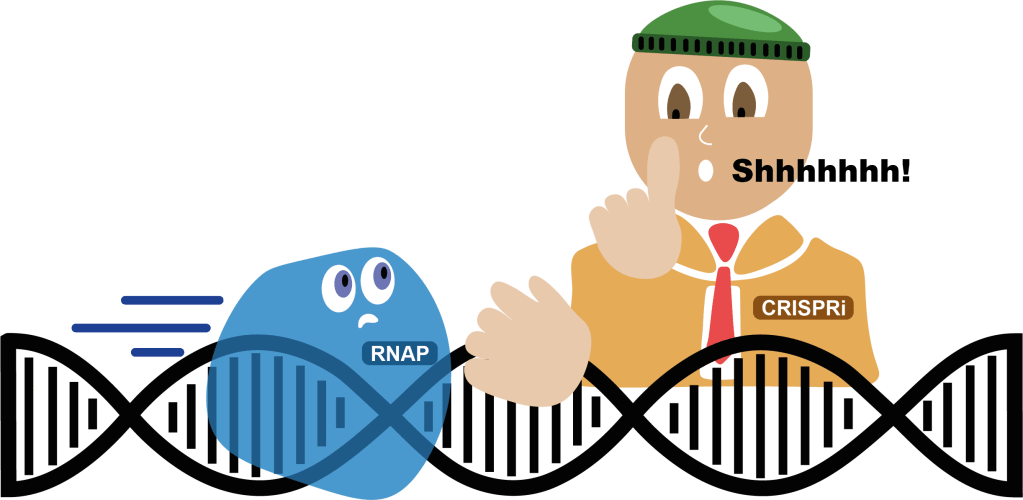

What is CRISPRi and how does it work?

CRISPR is a powerful gene editing tool that allows scientists to modify DNA sequences in cells with high precision (see our previous article about identifying targets). It is a valuable tool for research and therapeutic applications. It uses a system composed of two parts: (i) a protein enzyme called Cas9 which can bind and cut DNA, and (ii) an RNA molecule called the sgRNA, which guides Cas9 to a specific DNA sequence (learn more about the CRISPR-Cas system).

CRISPRi (interference) is a modified version of this tool where the Cas9 enzyme has been inactivated. It was named dCas9, for “dead” Cas9. This inactive enzyme can still bind DNA, but it cannot cut DNA. When dCas9 binds to DNA, it blocks DNA transcription, allowing for precise control of gene expression without modifying the DNA sequence. Since dCas9 blocks DNA transcription, it is said to “repress” gene expression. By adding a specific chemical called an “inducer”, scientists are able to switch the CRISPRi system “on” and “off” at will, adding a layer of control. The system can even be used to control the expression of multiple genes at the same time (multiplexing)!

CRISPRi technology is already being used in biotechnology, research and therapeutics, including:

Metabolic engineering: to redirect metabolic pathways in cells to produce specific compounds, such as biofuels or pharmaceuticals

Disease research: to study the role of genes in disease development, potentially leading to the identification of new drug targets

Synthetic biology: to build genetic circuits that can be used to control cell behaviour, such as the activation of specific pathways in response to environmental cues

What are the barriers?

Important factors in the design of the CRISPRi system determine the efficiency of the gene repression; how much the expression of the gene can be prevented. Previous researchers have used sophisticated, but somewhat limited methods, to control the efficiency of gene repression.

Examples include:

- altering the expression level of dCas9 or the sgRNA with different promoter strengths (initiator of DNA transcription)

- changing the concentration of the “inducer”

- varying the plasmid copy number from which the CRISPRi system is expressed

- modifying the sgRNA target position

- using a different host microorganism

However, these methods come with a number of drawbacks. Most notably, the design elements mentioned above must be modified for each new gene that is targeted in order to achieve the desired efficiency of gene repression. Testing different design elements is time-consuming and costly because our current understanding does not allow predictable, reproducible modifications to be made. Instead, trial and error are often required.

In a new study, the research group overcame many of these issues by uncovering structural elements of the sgRNA that can provide predictable levels of repression, irrespective of the target gene. Let’s find out how they did it.

Improving sgRNA designs

First, the group designed a quick and easy way to measure how effectively their system was repressing the target gene. They integrated the gene for a fluorescent protein (mCherry) in the genome of E. coli and where it would be constitutively (constantly) expressed. They then designed a library of different sgRNAs with different sequences for the target gene. The fluorescent protein allowed them to visualise which sgRNAs were most effective at repressing the gene – the less fluorescence, the more effective the repression.

Results showed that modifying the sgRNA sequence in a region called the tetraloop (and its flanking sequences) provided a set of sgRNAs with different repression efficiencies. The real game-changer is that when they switched the target sequence of the sgRNA to other genes, the modifications still provided predictable levels of repression (up to 45-fold). Not only that, but they observed fewer off-target effects (changes in the expression of non-related genes) but also no toxicity from either the “inducer” or the expression of dCas9. While their system was still somewhat sensitive to the concentration of the “inducer” that was added and the strength of the dCas9 promoter that was used, the sensitivity level was a vast improvement on the previous systems described above.

To better understand how the different sgRNA tetraloop sequences led to different levels of repression, the group used a computational approach which measures the change in free energy when the sgRNA and dCas9 interact. Analysing their library of sgRNAs with this method the group found that the free energy change correlated with the level of repression (and presumably the stability of the interaction between the sgRNA and dCas9). The next step was to demonstrate that the discovery could be applied to a real-world example.

Fine-tuning biosynthesis of lycopene in E. coli

As a proof of concept, the group chose to apply their new CRIPSRi technology to enhance the biosynthesis of lycopene. Lycopene is a natural red pigment in the carotenoid family of compounds. It’s the pigment that gives fruits like tomatoes and watermelons their distinctive red colours. Lycopene is a valuable compound due to its antioxidant properties which may have health benefits. Synthesis of lycopene is a complicated, multi-enzyme pathway that begins with simple precursors (like pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate).

These precursors are also used in the central carbon metabolism of bacterial cells and so are in high demand. This means that if the CRISPRi system is used to redirect too many of the precursor molecules away from central carbon metabolism and toward lycopene production, the cells will die. A careful balance is needed! This provided the perfect example to demonstrate the exquisite fine-tuning of the gene expression achievable with the novel CRISPRi system. The group designed 5 different sgRNAs with different levels of repression, targeting the enzyme which controls whether the precursor molecules enter into central carbon metabolism or into lycopene production. They then compared their system to a more traditional CRISPRi system which was unable to achieve the necessary regulation and killed the cells. Their system, however, significantly improved lycopene production (2.7-fold increase) and did not show any growth defects.

The new CRISPRi system was used to control gene expression in a predictable, robust fashion, irrespective of the target gene. It was shown to be effective in manipulating bacterial metabolic flux to improve the production of a highly valuable compound: lycopene. This new tool and future developments in CRISPRi technology will likely be important for humans to work with microorganisms, together pushing the limits of biotechnology.

Link to the original post: Gibyuck Byun, Jina Yang, Sang Woo Seo. CRISPRi-mediated tunable control of gene expression level with engineered single-guide RNA in Escherichia coli, Nucleic Acids Research, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad234.

Featured image: Made by author