Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Resource management in overworked microbes

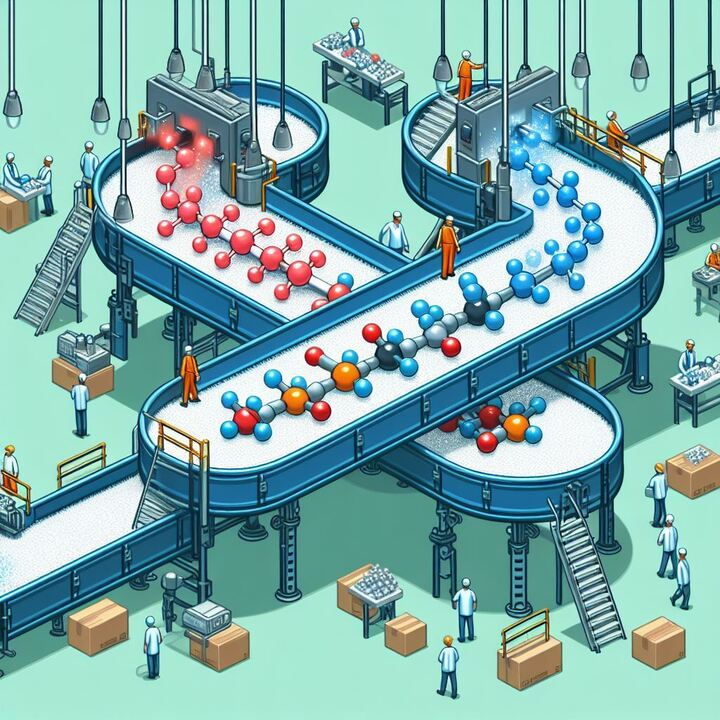

Microbes are like little factories producing all kinds of products. The microbes in cheese, for example, naturally convert milk to more tasty molecules. But we can also give microbes instructions to produce proteins that they don’t normally make, by inserting new genes.

Just like in a classic factory, however, there are limits to microbial protein production. In the factory, an urgent need to produce a certain good necessitates a re-organization: workers that previously worked in cleaning or lunch preparation might be employed for production as well. The result could be a slightly less clean factory, or not enough lunch preparation.

The same happens in microbes, but instead of the workers, it is the enzymes that are re-organized when production needs are high. When the amount of protein that has to be produced by a microbe is very big, we call this a metabolic burden. This burden can lead to a reshuffling of the cell’s metabolism, the network of reactions taking place in the cell. The way in which workers/enzymes are reallocated is called resource allocation.

In this study, the researchers looked at the resource allocation in Pseudomonas putida. They asked themselves how the reactions taking part in this bacterium (its metabolism) are reshuffled when it is forced to produce a lot of protein. How are the enzymes in this mini-factory re-organized?

To answer this question, they added a gene expressing a heterologous protein (a protein not normally produced by this organism) to P. putida. They put this gene under the control of an inducible promoter, which can be compared to a tap or a dimmer switch: the expression of the gene could be opened more or less depending on the amount of inducer fed to the bacterium. In this way, the researchers could test what would happen to the resource allocation in response to a high metabolic burden by turning the expression of the heterologous protein all the way up.

When the researchers opened the heterologous protein tap completely, the cells started to grow a lot less fast. This indicated that there was indeed a metabolic burden: the cells couldn’t keep up growth due to the high production needs. Compare this to the factory scenario described earlier: when lots of workers are forced to work on production, there will be less of them left for other tasks, such as growth. Indeed, P. putida’s metabolism turned out to be re-organized in this scenario. One sign of this reshuffling was the increased excretion of a compound called 2-ketogluconate (2-KG). Under normal circumstances, this compound is an intermediary in an alternative pathway to convert glucose to energy and help P. putida grow (see figure below). The research suggested that, due to the high level of heterologous protein production, P. putida had to reallocate its enzymes. They were now used for protein production instead of the continuation of the 2-KG pathway. As a result, 2-KG was excreted without being used.

Importantly, the research also showed that the production of the heterologous protein did not require extra carbon. To stick to the factory metaphor, think of a bread factory. The heterologous protein would be a new type of bread that did not require more flour (carbon), but did depend on more workers (enzymes), because it was made with a more complicated recipe. All in all, this research shows how the workers in the protein factory that is P. putida are reshuffled when they are forced to execute a difficult task. The outcomes give new ideas to optimise protein production in this bacterium.

Link to the original post: Vogeleer, P., Millard, P., Arbulú, A., Pflüger-Grau, K., Kremling, A., Létisse, F. Metabolic impact of heterologous protein production in Pseudomonas putida: Insights into carbon and energy flux control. Metabolic Engineering 81 (2024) 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2023.10.005

Featured image: Original image made with Bing Image Generator.