Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Unlocking Nature’s Secret Language

Although we can’t hear them, plants have a secret communication with their fellow soil inhabitants. Plants can release hundreds of different chemicals into the soil to communicate with thousands of different bacteria and fungi – and the bacteria and fungi can respond with their own unique chemical signals. This communication is essential for establishing a relationship between the plant and the microbe.

The plant-microbe secret language is almost as old as plants themselves, and they have come to rely on each other for different reasons, ranging from nutrition to pathogen defense. Scientists have long been interested in manipulating this line of communication for humanity’s benefit. Researchers have already manipulated a chemical signaling pathway between tobacco plants and the bacteria E. coli for disease control. Synthetic plant-to-microbe communication channels rely on what’s referred to as a sender device and a receiver device. Think about it as a game of catch, where the ball would be the sender and the mitt would be the receiver. However, developing the molecule, or the sender device, is no easy feat.

Many of these sender-receiver systems utilize a molecule called acyl-homoserine lactones. Bacteria use this molecule in something called quorum sensing, which lets the bacteria respond to population density. Over time, plants have learned how to eavesdrop on the bacteria by detecting acyl-homoserine lactones making this system a promising one for exploitation.

But natural chemical communication between plants and microbes is biologically very complex, so manipulating these systems for a desired effect doesn’t always result in the right outcome. Additionally, using acyl-homoserine lactones can often cause non-specific communication. In fact, many plants have developed molecules that mimic acyl-homoserine, which can prevent communication altogether.

However, new research using a quorum signal that comes from the bacteria Rhodopseudomonas palustris offers a promising alternative to harnessing the power of plant-microbe communication. Researchers introduced this quorum signal called p-coumaroyl-homoserine lactone into two different kinds of plant-safe bacteria that won’t make the plants sick. When the bacteria release the molecule in response to various stimuli, it can activate gene expression in the plants.

Designing the system

The researchers started on the plant side of things by designing the receiver to detect their bacteria-made signal. In this case, the receiver is something called a promoter. A promoter is a DNA sequence located just before the coding region of a gene; when the promoter is activated, it causes gene expression, subsequently leading to protein production. Without promoter activation, you wouldn’t get things like flowers because no proteins would ever be made.

Researchers used an existing promoter system but made a few changes to make it work better for their goal. After the promoter, they put in a regulator, which will help turn on or off their gene of interest in response to the bacteria signal. Researchers chose a regulator from a bacteria, but after a bit of modification, it was ready to be used in the plant itself.

Testing the system

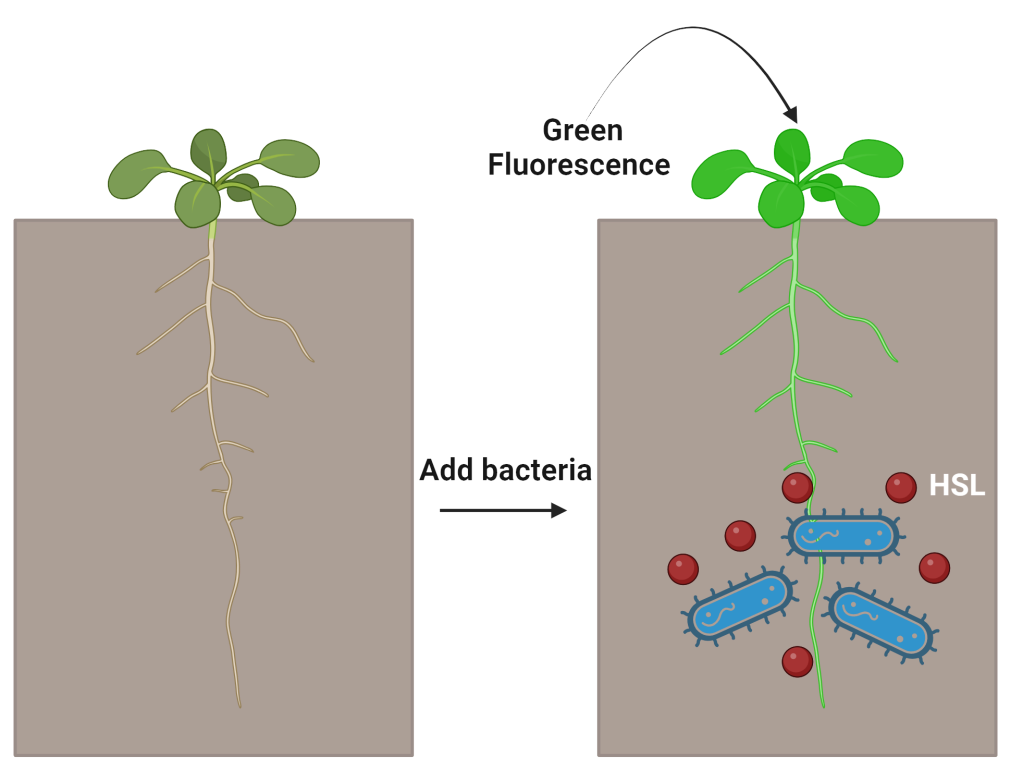

To test if their system worked, they used a green fluorescent protein as their gene of interest. If their system responded to their molecule, homoserine lactone, then they would see a bright green color under UV light. The homoserine lactone molecule could either be supplied externally or produced by bacteria residing in plant roots.

After putting their system into their chosen plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, the researchers applied the sender device homoserine lactone. While they saw a bright green color under UV light, it was primarily focused on the plant’s roots. But, the sender-receiver system was specific, as no green fluorescence was seen when any other molecule was used. This means their system was working!

Now, it was time to make bacteria that could release homoserine lactone. They designed a bacteria to convert the amino acid tyrosine, an essential building block for proteins, into homoserine lactone.

The researchers wanted to test if the bacteria they developed to produce homoserine lactone would also result in green fluorescent protein activation. When they put their engineered plants and bacteria together, they saw green fluorescence in plant roots. Even when the plants and bacteria were together in non-sterile soil with other microbes, the sender-receiver system still worked, meaning this system could someday be applied to crops to activate certain genes.

To increase the system’s sensitivity, researchers utilized different molecules to activate homoserine lactone production. Certain genes can be activated by different stimuli, like molecules. In this case the researchers wanted to turn on the gene in the bacteria that produces homoserine lactone. When small molecules like antibiotics were added to the media with their engineered bacteria, it turned on homoserine lactone production.

Lastly, to test the real-world applications of their system, they made bacteria that produced homoserine lactone in response to arsenic. Arsenic is a heavy metal that can stunt plant growth but is a common pollutant on farmlands. When the engineered Arabidopsis plants and bacteria were together in the presence of arsenic, the plants glowed green in response to the expression of the green fluorescent protein. This could someday be used to monitor agricultural conditions or even make plants put up defense systems in response to the presence of arsenic.

This research lays the groundwork for a novel approach to engineering plant-microbe interactions, and in the future, we may be able to utilize the plant’s and microbes’ secret language to develop crops that grow better and are pathogen-resistant.

Link to the original post: Boo, A., Toth, T., Yu, Q. et al. Synthetic microbe-to-plant communication channels. Nat Commun 15, 1817 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45897-6

Featured image: Image created by the author in Biorender.com.