Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Your Body’s Timberland: Microbial Ecology Fighting Cancer

Picture a forest. Trees, shrubs, birds, mammals, insects, microbes – all different species interacting and competing with each other, from the treetops to the soil. This is what scientists call an “ecosystem.” Deserts, oceans and lakes are some other examples. But did you know your body is an ecosystem too? Communities made up of trillions of microbes live inside and on the surface of the human body. These bacteria, fungi and viruses are known as the “human microbiome.” Every person’s microbiome is totally unique, like a fingerprint. It plays an important role in human health, making it an attractive target for scientific research.

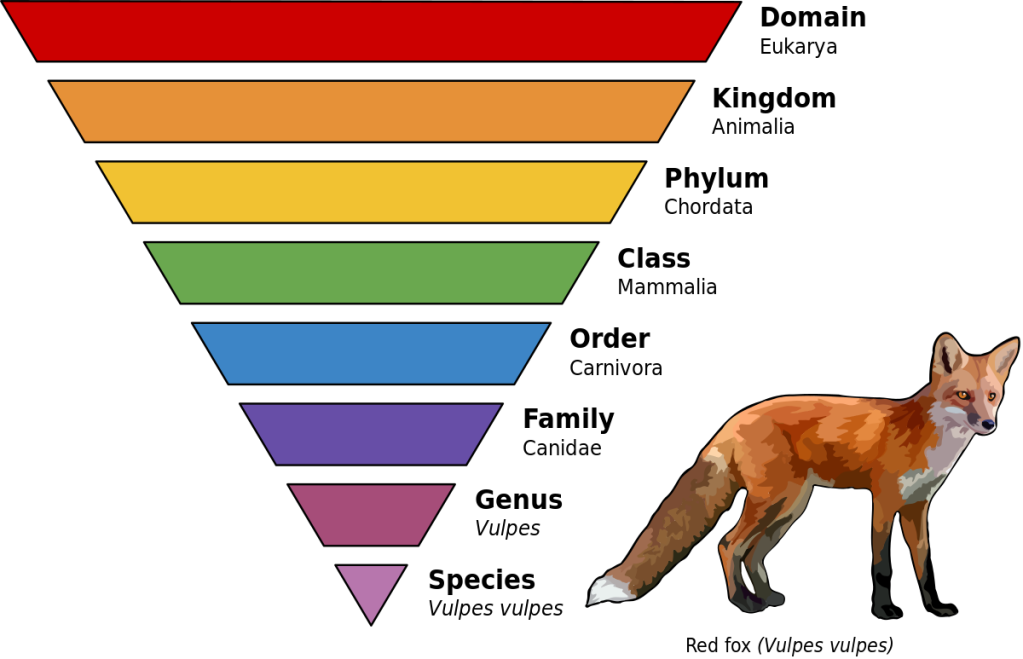

The structure of these communities can be described in the same way as terrestrial ecosystems. Richness is a measure of the number of different species present. Diversity is a measure of richness combined with evenness. Measuring variety, it accounts for not only the number of species present, but how evenly they are proportioned.

With this in mind, researchers at the University of Michigan recently studied changes in the oral microbiome of patients undergoing treatment for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). OSCC is the most common type of oral cancer, and cases are expected to keep rising globally.

What they did

Researchers took saliva samples from OSCC patients at 2 timepoints: once before starting treatment (baseline), and once at 6 months after finishing treatment. These samples were genetically sequenced to determine the makeup of the oral microbiome. A total of 48 patients had their samples sequenced: 33 who received chemoradiation (a combination of both chemotherapy and radiation), and 15 who received surgery alone.

Researchers also measured the amount of DMBT1 present in the samples. DMBT1 is a protein found in saliva that plays an important role in maintaining the oral environment. It interacts with other molecules and regulates processes related to the immune system.

This was the first-ever longitudinal (repeated samples over a period of time) investigation of the salivary microbiome in OSCC patients. Previous studies compared saliva samples from OSCC patients to samples from healthy controls. This study design allows patients to serve as their own controls – they’re compared against themselves over time.

What they found

In patients treated with surgery alone, there were no significant differences in microbiome structure. In patients who underwent chemoradiation, there was a significant difference in microbiome structure. While there was no notable change in diversity, richness was greatly decreased after treatment. This means there were fewer different kinds of bacteria present in their saliva. At the phylum level, Firmicutes increased while Bacteroidetes decreased.

Patients in the chemoradiation group were further divided into two groups after 6 months: responders (cancer-free) or non-responders (cancer came back after treatment). Between these groups, the types of bacteria present in their samples were significantly different both before and after treatment.

DMBT1 levels were significantly increased after treatment in both the chemoradiation and surgery groups. This suggests that the presence of OSCC causes DMBT1 levels to decrease. To further test this theory, researchers conducted a similar experiment on mice. Adult mice were injected with cells that caused them to develop a cancer similar to OSCC. Their saliva was extracted and DMBT1 was measured. Healthy control mice also had their saliva examined. DMBT1 levels were greatly decreased in the mice with cancer, compared to the control mice. The mice received no treatment. This result strengthens the theory that OSCC alone leads to a decrease in salivary DMBT1.

The researchers found that DMBT1 levels were related to changes in the oral microbiome. At the genus level, Leptotrichia was more abundant pre-treatment, and Gemella was more abundant post-treatment.

Why it matters

Unfortunately, OSCC often comes back even after treatment. Repeated biopsies of the mouth are expensive and unpleasant. Monitoring patients for cancer recurrence by sampling their saliva is an attractive concept. In the future, doctors might even be able to use this information to guide treatment options. Would a patient respond better to surgery, radiation, chemotherapy? Or some combination of the three? An individual’s microbiome could give us the answer. That might still be a ways off, but this study lays the groundwork for future research.

It also highlights the similarities between humans and the environment around us. We are both a species in an ecosystem, and an ecosystem in and of ourselves. Just as the diversity of tree species can be useful in predicting a forest’s response to an environmental disturbance, the diversity of our microbiome has the potential to help predict our body’s response to disease.

Link to the original post: Medeiros, M.C.d., The, S., Bellile, E. et al. Salivary microbiome changes distinguish response to chemoradiotherapy in patients with oral cancer. Microbiome 11, 268 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-023-01677-w

Featured image: Ryan McWhinnie