Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Antarctic Fungi Could Help Fight Leukemia

Few species survive the extreme environments of Antarctica. Freezing temperatures are only the tip of the iceberg; any life attempting to eke out an Antarctic existence must endure water scarcity, little light, harsh winds, and intense ultraviolet radiation. For the small, hardy number of species that do carve out a niche there, adaptation is the game – and this includes life at the microscopic level.

Microbes able to thrive in Antarctica’s extreme conditions are of great interest to researchers because they may have evolved novel biochemical pathways to survive. These pathways could synthesize biomedically- or biotechnologically-relevant compounds both known and unknown.

A recent paper underscores the importance of exploring this understudied microbial ecosystem. From the root systems of Antarctic mosses, researchers identified several candidates of fungal microbes capable of producing a crucial anti-Leukemia enzyme, in the absence of 2 factors often associated with side effects during treatments.

What is Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia?

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, also called Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL), is the most common form of cancer in children, representing 25% of diagnoses of patients under 15. To break down the term, “Acute” refers to the fact that the disease progresses quickly, while “lymphoblastic” describes the cell types that the cancer targets: white blood cells called lymphocytes. ALL replaces healthy lymphocytes with immature ones that can’t properly fight infections. These cells circulate in the bloodstream, growing and dividing in various tissues and organs and resulting in a range of symptoms.

How guinea pigs brought ALL patients new hope

For the first century after the initial description of the disease, ALL was largely fatal; however, with the mid-twentieth century came the advent of chemotherapy, and with it, better prospects for ALL patients. Then, in 1963, a paper discovered that the enzyme L-asparaginase, isolated from guinea pig serum, inhibited growth of lymphoma cells. Enzymes are biological catalysts, usually proteins but sometimes RNA, that speed up cellular biochemical reactions and can be used repeatedly.

L-asparaginase hydrolyzes (breaks down with the help of water molecules) asparagine into two other compounds, ammonia and aspartic acid. This is biologically significant because asparagine is an amino acid, one of the building blocks of proteins. When a cell is deprived of asparagine long-term, it can lead to cell death. Non-cancerous cells can make their own asparagine, but ALL cancer cells can’t, and have to acquire it from outside sources. Therefore, L-asparaginase treatments selectively kill cancer cells in ALL patients, because once their asparagine stores are depleted, they can’t make more. Inclusion of L-asparaginase in ALL treatments significantly improves patient outcomes.

The catch (course there’s a catch)

The L-asparaginase used to treat ALL is “farmed” from prokaryotic organisms, specifically Escherichia coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi. However, L-asparaginase made in these organisms often has two other enzymes with it: L-glutaminase and urease, whose presence can result in severe side effects which are difficult and costly to filter out. A major area of research in the ALL field now centers around finding microbes that produce L-asparaginase alone, without these other factors.

de Andrade et al., 2023 were not the first to search for fungal producers of L-glutaminase- and urease-free L-asparaginase in Antarctica – that was another research group, in 2019. However, de Andrade et al., 2023 is the largest-scale – and only the second to date – to explore the microbes of the region for this purpose, and was able to identify three novel candidates (!) for production of this crucial enzyme.

Experiments and findingsIn 2019 and 2020, scientists aboard the Brazilian Antarctic Operation XXXVIII research vessel collected samples of two species of mosses, Polytrichastrum alpinum and Sanionia uncinata, from two sites on the Keller Peninsula of Antarctica’s King George Island (Fig. 1). Healthy samples selected were examined for isolation of endophytic fungi. Endophytes are microbes that colonize plant tissue without harming the host.

Image source: de Andrade et al., 2023.

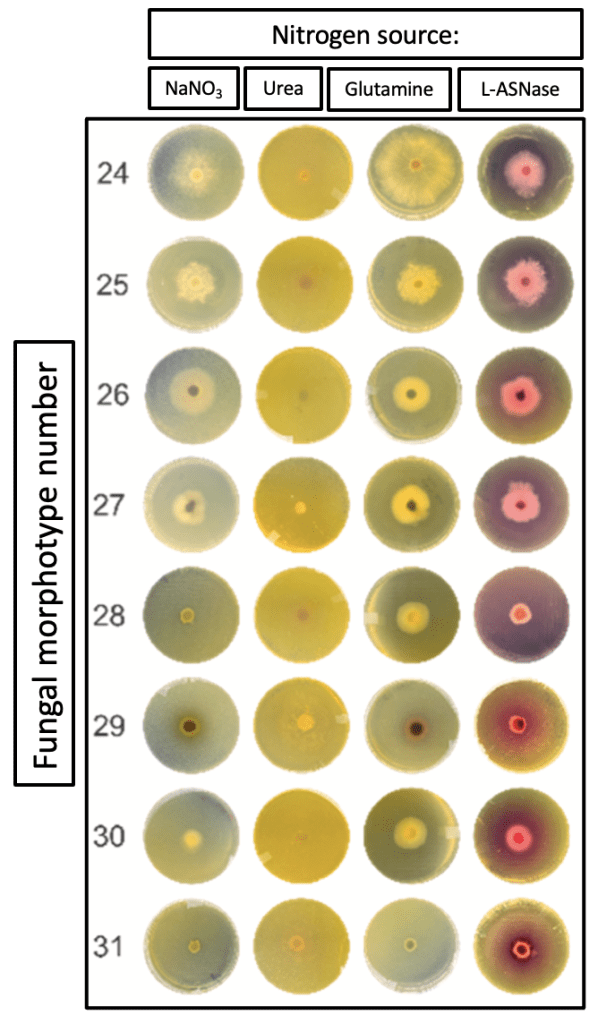

504 moss samples were transported to the laboratory on board the Brazilian Polar Ship Almirante Maximiano, where they were disinfected, fragmented, and grown on Petri dishes. As different fungal colonies grew, they were further isolated, purified, and identified. Initial identification was based on morphology – AKA, physical characteristics such as colony size, texture, and shape (Fig. 2). 161 total fungi were isolated, then sorted into 31 distinct morphotypes.

Researchers sought any fungi producing L-asparaginase, glutaminase, and urease in solid medium. While some exhibited no enzyme production, others made L-asparaginase in conjunction with one or both of the others. Excitingly, 13 morphotypes produced L-asparaginase alone, though only 8 of these demonstrated “robust” production (Fig. 3). These were then tested for ability to produce the enzyme in liquid medium.

Lastly, enzyme production of the isolates was optimised via the Taguchi method to identify the most optimal combination of temperature, pH, L-asparagine concentration, and glucose concentration to yield high levels of L-asparaginase – which turned out to be 30 C, pH 7, 11 g/L of L-asparaginase, and 1 g/L glucose. Temperature was the most influential aspect of the growth environment on L-asparaginase output.

For the three best fungal producers of L-asparaginase, further genetic-level identification was in order, and DNA sequencing identified the isolates as Epicoccum nigrum, Collariella virescens, and Peroneutypa scoparia. All three fungi produced L-asparaginase without glutaminase or urease, rendering them viable candidates as potential new sources for biosynthesis of this critical anti-Leukemia enzyme. Furthermore, they all exhibited notable boosts in enzyme production under the Taguchi-method-optimised conditions, demonstrating that yields can be effectively scaled up.

Takeaways

Progress, in science, requires a combination of innovation with rigorous repetition. The importance of the latter is arguably too often overlooked at the publication level, which places heavy weight upon the novelty of research. This can push researchers towards innovative and groundbreaking discoveries, but can also prevent errors and inaccuracies from being uncovered – for a rabbit hole of an example, read about this recent upset in the Alzheimer’s field.

Though another research group in 2019 first published on the discovery of fungal endophytes in Antarctica capable of producing L-asparaginase without glutaminase or urease, this current study is a crucial stepping stone in the field for two reasons: 1), its results support and validate those of the previous study; and 2), it discovered additional, novel fungi capable of producing this anti-Leukemia enzyme alone.

This kind of result doesn’t mean we stop looking for further options for cancer therapies in the root systems of moss at the end of the world. Precisely the opposite: this study means we should absolutely keep looking, because something real is out there – a real opportunity for hope, that amid the ice and radiation and darkness, lies microscopic life with survival secrets that could help us in undiscovered ways.

Featured image: de Andrade et al., 2023.