Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

How the Microbiome Determines Preterm Lung Health

In 2020, an estimated 13.4 million babies were born preterm. This means between 4-16% of all babies are delivered before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Preterm birth complications are the leading cause of death among children before the age of five.

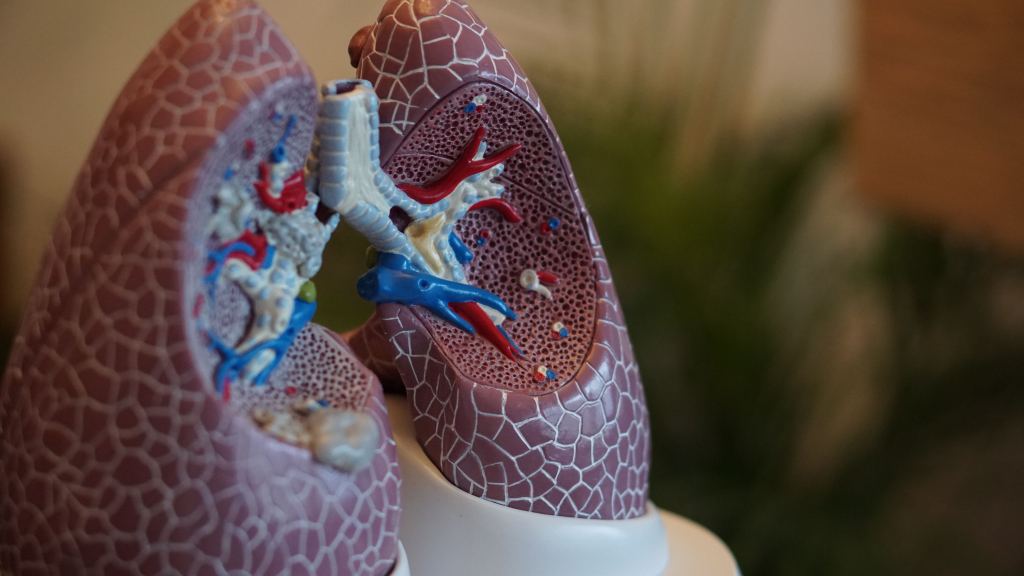

Respiratory-related complications remain the leading cause of death in preterm infants, often due to underdeveloped lungs. To treat these illnesses, preterm babies are often put on mechanical ventilation or other forms of respiratory support. However, oxygen supplementation can cause a slew of other problems because of the sudden exposure to oxygen their bodies were unprepared for.

A fetus’s lungs are not exposed to oxygen in the womb, as most oxygen exchange occurs through the placenta. So, when a baby is born before their lungs are fully developed, they are exposed to oxygen concentrations that their lungs are not ready for, and using supplemental oxygen can worsen this problem. This excess of oxygen can damage lung tissue, causing abnormal lung development and leading to long-term complications.

However, not providing a preterm infant with supplemented oxygen often results in a much worse fate. Researchers are tasked with the difficult challenge of finding a way to give oxygen to these infants but minimize any negative impacts – and researchers in the Willis lab have found that the microbiome may hold the answers.

In recent years, the human microbiome has been shown to be vital to health, affecting everything from mental health to susceptibility to cancer. So, it is no surprise that the microbiome also plays a crucial role in lung development and wound healing. The Willis lab initially wanted to determine if oxygen supplementation could affect gene expression but ultimately found that it could affect the gut microbiome.

Researchers first exposed preterm infants to high oxygen levels to measure the expression of various genes in their lungs and gut. To do so, they looked at changes in gene expression after exposure to high oxygen levels in newborn mice. They found expected lung structural changes but also that some immune-related genes were overexpressed. However, what piqued the researchers’ interest was the changes in the expression of antimicrobial peptides in the infant mice’s guts. Antimicrobial peptides are essential proteins that help kill things like bacteria, and are involved in wound healing and tissue protection.

When the mice pups were exposed to high oxygen levels, antimicrobial peptides in their gut, specifically their terminal ileum, decreased. The terminal ileum in preterm infants is highly susceptible to enterocolitis, an inflammatory disease that can be fatal. Lysozyme, a crucial antimicrobial peptide, was expressed less in the terminal ileum in mice exposed to excess oxygen (Figure 1).

To further confirm the effect of oxygen on antimicrobial peptide production in the gut, the researchers turned to organoids. Organoids are miniaturized versions of organs produced in labs, often used to eliminate other systems in the body, like interactions with other organs that affect scientific results. Small intestinal organoids exposed to elevated oxygen levels saw increased expression of inflammatory genes and decreased expression of antimicrobial peptides. Similar to what was seen in the mice’s terminal ileum.

Because of the effect of the oxygen on antimicrobial peptides, it made sense there would be an effect on bacteria. When looking at the microbiome in the gut of mice pups exposed to high oxygen levels, they found a difference in bacterial community composition in the gut compared to mice not exposed to high oxygen levels. Specifically, there was an increase in Staphylococcus bacteria (Figure 1).

While Staphylococcus is commonly found in the gut, it has yet to be associated as a beneficial member of the gut microbiome. The bacteria alter the structure of the gut microbiome, and at high levels, some strains can become pathogenic. An increase in Staphylococcus levels can, therefore, mean bad news for the body as a whole.

Decreases in antimicrobial peptides such as lysozyme explain the increases in Staphylococcus bacteria. Through the direct link between a decrease in lysozyme and an increase in Staphylococcus, researchers tested if decreases in lysozyme were responsible for lung injury in mouse pups.

Mice pups fed extra lysozyme had their lung structures and function improved after exposure to higher oxygen levels than the rest of their litter mates (Figure 2). Interestingly, their natural lysozyme production also increased upon observing gene expression changes. Furthermore, their Staphylococcus bacteria levels returned to normal, supporting the idea that lysozyme keeps the gut bacterial community in check.

But do the lysozyme-induced changes affect more than just the gut?

The additional lysozyme in the diet also changed lung gene expression. Mice exposed to high oxygen levels and fed lysozyme still showed higher expression of inflammation-related genes compared to mice without exposure. However, adding lysozyme did help reduce some of these effects.

Current treatments for preterm infants to reduce the effects of early oxygen exposure are limited. Some studies found that probiotics reduce a breathing disorder called Bronchopulmonary dysplasia associated with early oxygen exposure. However, the Food and Drug Administration recently advised against probiotic treatment as it has been associated with sepsis in a small number of preterm infants – leaving doctors with few treatment options.

It has long been thought there is communication between the guts and lungs, affecting each other, termed the gut-lung axis. Research in the Willis lab shows that this communication greatly impacts overall lung health in preterm infants – and supplementing lysozyme in preterm infants’ diets could be a therapeutic to reduce the effects of oxygen exposure.

This research further expands on our knowledge of the human microbiome and how it relates to our health – our bacteria may have just as much of a say in our well-being as we do.

Link to the original post: Abdelgawad, A., Nicola, T., Martin, I., Halloran, B. A., Tanaka, K., Adegboye, C. Y., Jain, P., Ren, C., Lal, C. V., Ambalavanan, N., O’Connell, A. E., Jilling, T., & Willis, K. A. (2023). Antimicrobial peptides modulate lung injury by altering the intestinal microbiota. Microbiome, 11(1), 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-023-01673-0)

Featured image: Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash