Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Breathless: The Impact of Air Pollution on Microbial Balance

As air pollution has a large part of the world’s population in a chokehold, it is essential to talk about the extent of its impact on our health and well-being. Research has shown the negative effect of air pollution on cardiovascular, pulmonary, and brain functions. The components of air pollutants like NOx- Nitrogen oxides, ozone(O3), particulate matter (PM), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are already known to be harmful to human health. Unfortunately, the negative impacts of air pollution are not limited to human health, it has socio-economic implications as well. A Chinese study conducted in 2021 highlights the loss of human capital. They observed that talented college graduates chose to migrate in response to increased air pollution in Chinese cities. A phenomenon often referred to as “brain drain”.

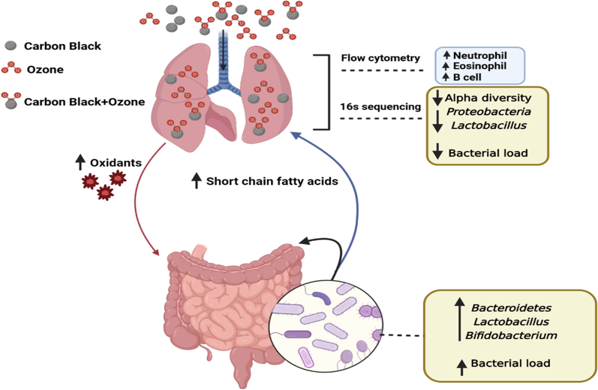

Studies have already established the harmful effects of air pollution on human health and we are left with the question- HOW do these air pollutants lead to chronic illnesses or functional impairments? A team of researchers studied the alteration in microbial composition of the lung and gut in mice exposed to carbon black (CB) and ozone (O3) to help understand the question better. Most of the research on the negative impacts of air pollution on human health is focused on lung disorders and relatively less research on studying the impact on our gut. Moreover, the majority of studies targeted single air pollutants only.

Here, Mazumdar and the team aim to delineate lung and gut microbiome changes and establish the lung-gut axis with better accuracy.

The experiment:

Set-up includes a whole-body inhalation exposure system, where groups of mice are completely exposed to aerosols of carbon black (CB), ozone (O3), or a mixture of CB + O3. Levels of O3 and CB are maintained specific to each group. There were four groups of mice and each group was exposed to the following conditions-

- Group 1: filtered air

- Group 2: CB (10 mg/m3)

- Group 3: O3 (2 ppm)

- Group 4: CB +O3 (10 mg/m3 + 2 ppm) co-exposure.

Identifying the microbiota-

Samples from all groups of mice were taken for processing and analysis. DNA was isolated from those samples and the specific region of the 16S rRNA gene (V3-V4 regions in this case) was amplified using PCR. This amplification step generates many copies of the gene of interest which was then sequenced through next-generation sequencing (NGS) and massive amounts of sequence data were generated. This sequence data was used to assign taxonomic identities and to understand the richness (types of microorganisms present) and evenness (even distribution of microbial species across samples or individuals) of the microbial communities, and statistical analysis to find microbial composition differences between microbial groups.

Results point to changes in the microbial community of lungs in response to different exposure conditions. A significant impact on microbial richness in the lungs was seen after CB + O3 exposure. Researchers also found the presence of bacterial families which are associated with lung pathophysiology. Only the control group (group 1), receiving filtered air, had bacteria from a potentially beneficial Acetobacteraceae family.

As for the gut microbiota, changes in bacterial abundance were seen. However, the diversity of gut microbiota remained the same after multiple exposures. Results also revealed an increase in the relative abundance of several beneficial gut bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium. In addition to this, changes in the bacterial population of Oscillibacter and Anaeroplasma were observed. Interestingly, both have contradictory implications in the intestine. While an increase in the population of Oscillibacter may suggest a reduction in the integrity of the gut barrier, making it more permeable, Anaeroplasma is associated with improved gut barrier function.

Why were the results different for gut and lung microbiota? Why did the lung and gut microbiota not show similar changes in composition?

Perhaps this suggests an active homeostatic adjustment in the gut microbiome to counter the negative impacts of inhalation exposure on the lungs.

What else did they find out?

A two-way relationship exists between microbiome and inflammation. Microbes can trigger inflammatory pathways and inflammatory immune cells are known to cause microbial composition changes. The researchers observed an increase in eosinophils, B-lymphocytes, and neutrophils upon exposure to the pollutants.

To add to this, results also revealed an increase in acetate and propionate levels, short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), after multiple co-exposures. Their presence is suggestive that perhaps they play a role in regulating the inflammatory response. The study also highlights specific microbiota members known to produce these SCFAs, indicating a potential source for the observed changes.

Moreover, the research suggests when mice were exposed to both carbon black (CB) and ozone (O3), the impact on oxidative stress was stronger compared to exposure to either CB or O3 alone. This oxidative stress was linked to changes in lung microbiota. study implies that the amount of bacteria present in the lungs is closely related to the levels of oxidative stress in the body, and there is an inverse correlation between the two. This suggests that the presence of certain types of bacteria in the lungs might play a role in reducing oxidative stress levels, thereby potentially providing some protection against the harmful effects of these stressors. when there are fewer bacteria or a decrease in bacterial load, the levels of oxidative stress tend to rise, possibly leading to an increased risk of inflammation and damage to the lung tissues. the intricate interplay between the microbiome and the body’s response to stress.

Takeaway-

The study observed changes in microbial abundance and composition in both lungs and gut. However, we still need to understand the exact mechanisms behind these changes and their implications in the development of metabolic diseases. Only a better understanding of the lung-gut inflammation connection can aid in the development of targeted preventive and treatment strategies. This is exactly what we need since air pollution is on the rise and shortening life spans already.

Link to the original post: Mazumder, M.H.H., Gandhi, J., Majumder, N. et al. Lung-gut axis of microbiome alterations following co-exposure to ultrafine carbon black and ozone. Part Fibre Toxicol 20, 15 (2023).

Featured image: Bing Image Creator