Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Salivating Enhancement of Dengue Virus

Mosquitoes, the bane of every summer. These creatures love to ruin a perfectly laid out picnic or just a relaxing hike in the great outdoors with their thirst (and hunger too) for blood. Not only can these flying insects be a temporary inconvenience when trying to get a breath of fresh air, but they can transmit some of the world’s deadliest diseases such as malaria and in the case of this article Dengue virus.

What is Dengue virus?

Approximately, 50% of the world is at risk of Dengue with it being more prevalent in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Dengue is a viral infection that is transmitted from the bite of mosquitoes, specifically the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Of course, when mosquitoes bite, they release some saliva into your blood as well and this paper took a deeper dive into the assistance this saliva brings to the Dengue virus.

The Mysteries of Mosquito Spit

Numerous studies have shown that mosquito saliva enhances the infectivity of mosquito-transmitted pathogens. As a result, there is vast interest in investigating what factors of the saliva provide this enhancement. The authors of this paper investigated one such factor called subgenomic flaviviral RNA (sfRNA). This is a strand of RNA that does not code for any proteins and is a smaller section of the flaviviral RNA genome (gRNA). Flavivirus being the genus of the virus to which Dengue virus belongs. To probe into the functions of this sfRNA, the experimenters orally-infected A. aegypti mosquitoes with a strain of Dengue virus type 2 called the New Guinea C strain (DENV2 NGC). To confirm that sfRNAs existed in the infected mosquito saliva, the researchers ran a Northern Blot which detects the presence of RNA in a sample (saliva in this case).

All Aboard the EV Express

Once confirmed, the scientists posited the question of where these sfRNAs are located with regards to the saliva. To accomplish this, infected saliva was subjected to treatment with ribonucleases (RNases) which are enzymes that degrade RNA into smaller components. What they found was that sfRNA in uninfected saliva was broken down by the RNases whereas sfRNA in infected saliva was resistant to RNases treatment.

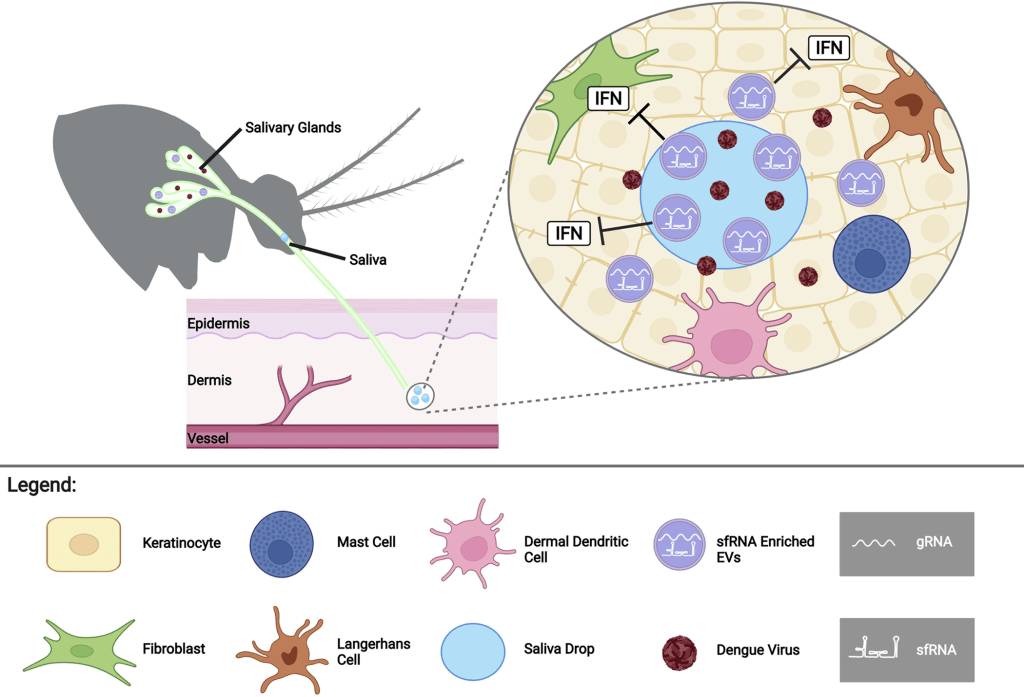

However, if the infected saliva was pretreated with a detergent (Triton X-100), then the sfRNA was degraded by the RNases. Thus, the researchers concluded that the sfRNA in infected saliva is contained in structures that protect it from being degraded by these ribonucleases, but this structure can be compromised by detergents. Utilizing these findings, the investigators hypothesized that sfRNA is likely held within the salivary extracellular vesicles (EV) which are particle-like structures that arise from the cell membrane used to deliver necessary materials to other cells (Figure 1).

First, transmission electron microscopy was used to identify EV-like particles in both uninfected and infected saliva samples. Then the scientists used a technique called RNA-FISH to confirm that sfRNA was indeed contained within these EV-like particles. RNA-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a method to detect and localize RNA within a fixed sample. A fragment of single-stranded nucleic acids attached to a fluorescent dye called a probe is used. This probe binds to the complementary sequence of viral RNA within the saliva and fluoresces and can be visualized through microscopy. Researchers detected numerous EVs labeled with the fluorescent probes within the infected saliva indicating the presence of sfRNA within the particles.

Infection Enhanced

Now that sfRNA has indeed been confirmed to exist within the saliva of mosquitoes infected with Dengue virus, the researchers turned to how these sfRNAs mediate Dengue infectivity. Saliva from mosquitoes infected with different DENV2 strains was taken and used to infect a human cell line. Of note, these saliva samples were pooled together based on strain and each pool had a varying sfRNA level. Interestingly, what the researchers found was that the higher the sfRNA level, the more viral replicates there were. To further elaborate on these findings, investigators transfected a strand of RNA from a section of the Dengue genome, as a means to mimic sfRNA delivery, into a human cell line 2 hours prior to subsequent DENV2 infection. This transfection increased the levels of DENV2 RNA within infected cells significantly.

Bye Bye Immunity

To further look at the sfRNA’s effect on infectivity, the researchers also took a look at the host response Dengue sfRNA. The host response to infection is composed of 2 types of immune response: adaptive immunity and innate immunity. For this experiment, researchers looked at innate immunity which is the body’s first line of defense against pathogens. These responses are non-specific and general which means they don’t discriminate based on the pathogen. One aspect of innate immunity is a group of proteins called interferons (IFNs) which respond when the body is infected with a virus. To look at how sfRNA affects the interferon response, the authors repeated the previous experiment in which sfRNA was transfected into cells. This time they measured levels of interferons by measuring the level of mRNA for both IFNs and a group of genes that respond to the production of interferons called interferon-stimulating genes (ISGs) that help to inhibit viral replication. A normal transfection of foreign RNA would increase mRNA levels of both IFNs and ISGs, but the strand mimicking sfRNA repressed both interferon and interferon-stimulating gene mRNA levels indicating that sfRNA is inhibiting interferon induction and signaling in human cells. An inhibited interferon response means a decreased immune response and an increase in the infectivity of Dengue virus.

Mosquitoes will continue to be a summer pest, but with new insights into pathogen transmission factors associated with a mosquito transmission route, we can begin to develop new therapeutics to combat these microbes.

Link to the original post: Yeh SC, Strilets T, Tan WL, Castillo D, Medkour H, et al. (2023) The anti-immune dengue subgenomic flaviviral RNA is present in vesicles in mosquito saliva and is associated with increased infectivity. PLOS Pathogens 19(3): e1011224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1011224

Featured image: Image by Егор Камелев from Pixabay