Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Bacterial Poseidon: Protecting Oceans from Plastic

Oceans are mysterious. In fact, it is estimated that humans have only explored about 5% of the ocean. However, our actions have everlasting effects even in the ocean’s most treacherous depths. Plastic, as you may expect, is the adversary. Reportedly, plastic bags have made it to the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific ocean, which is famous for being the deepest, most remote oceanic trench! Plastic in the ocean is of pressing concern: marine species are ingesting, suffocating, or getting entangled in contaminating plastic. Plastic pollution affects the growth, development, and reproduction of marine organisms. The oceans are thus unmistakably gasping for breath, caught in an unyielding chokehold of plastic pollution.

To overcome this devastating problem, scientists have been working on ways to degrade oceanic plastic waste so that it doesn’t pose such a big danger to marine life. Previous research has shown that certain marine microorganisms have evolved to degrade plastics. This is really fascinating and could be just the solution we need! However, no research so far has resulted in a product which can degrade plastic in the oceans. In a paper published earlier this year, Gui and colleagues set out to discover a new microorganism that degrades plastic, and potentially find a mechanism that can be converted into a commercially usable bio-product.

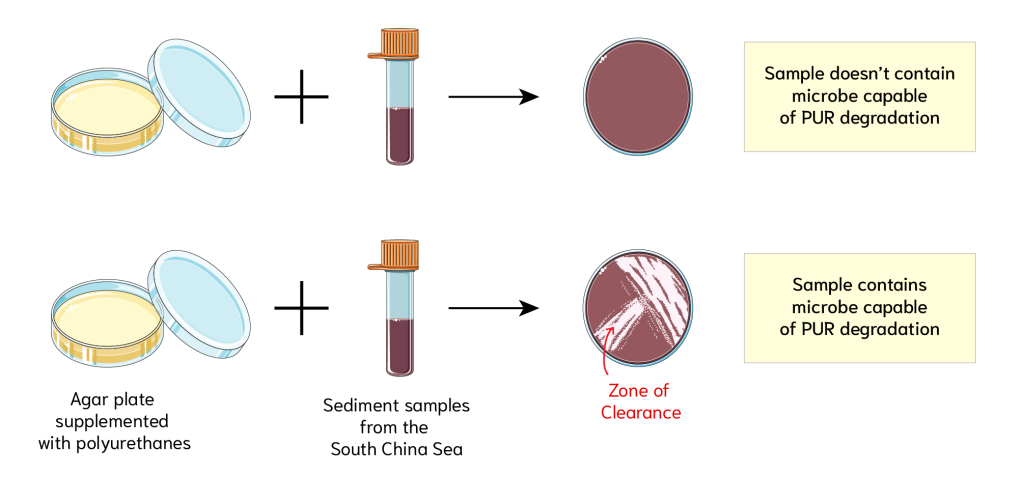

For the purpose of this study, the authors primarily focused on polyurethanes (PUR), a type of plastic that has wide utility in the furniture, construction, footwear, and transportation industries. Polyurethanes are a concerning pollutant because they cannot be broken down easily in nature and can stick around for hundreds of years. Here, the authors use waterborne polyurethane to screen for microbes that can degrade this plastic. The authors obtained microbes from sediment samples collected from the South China Sea. They took these sediments and spread them on agar plates containing waterborne PUR. If the sediment contains any bacteria that can degrade PUR into a water-soluble substance, a clear zone appears around the colony (Figure 1). These water soluble substances are usually products of plastic depolymerization, and can be easily degraded into alcohols, ketones, and acids. Using this technique of observing zones of clearance, the authors can identify samples that may contain a microbe of interest.

Enter our bacterial Poseidon: a new bacterial strain the authors call B. velezensis GUIA! This bacterium collected from the deep-sea cold seep degrades PUR, both on the author’s agar plates and in liquid media. Once the authors identified this bacterium, they became interested in figuring out the mechanism it uses to degrade plastic. If we know the specific enzymes involved, we are one step closer to creating a product that has real-world applications. To figure out the enzyme in question, the authors took this bacterium and grew it with and without PUR. Their idea was that when grown in the presence of plastic, the bacterium should produce the enzymes it needs to degrade this plastic. If we measure which genes are being highly expressed in the two different growth conditions, we can begin narrowing down on which genes are required for plastic degradation. Using this method, the authors found that strain GUIA expresses genes including lipases (enzymes that break down fats) and proteases (enzymes that break down proteins), both of which have been previously associated with PUR degradation. Excitingly however, the authors also found a new gene Oxr-1 that has not previously been linked with plastic degradation abilities (Figure 2A).

Oxr-1 is an oxidoreductase which means that it catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule to another. To determine whether Oxr-1 is the primary enzyme used for PUR degradation, they took the gene encoding this enzyme and put it in a bacterium that doesn’t usually degrade plastic. Using this technique, they asked whether the presence of Oxr-1 alone could result in plastic degradation by this bacterium – and it did! (Figure 2B) So, the authors not only found a new bacterial strain capable of polyurethane degradation but also identified a specific enzyme that can carry out this degradation!

In future work, the authors are interested in further exploring the degradation mechanism of Oxr-1 and generating mutants of this enzyme that have higher degradation efficiency. Developing a version of Oxr-1 that is highly efficient at PUR degradation may lead to a product that can begin freeing our choking oceans.

Link to the original post: Gui, Z., Liu, G., Liu, X., Cai, R., Liu, R., & Sun, C. (2023). A Deep-Sea Bacterium Is Capable of Degrading Polyurethane. Microbiology Spectrum, 11(3), e00073-23. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00073-23

Featured image: created using Craiyon and Adobe Illustrator.