Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Bacterial Sixth Sense: Detecting Death for Survival

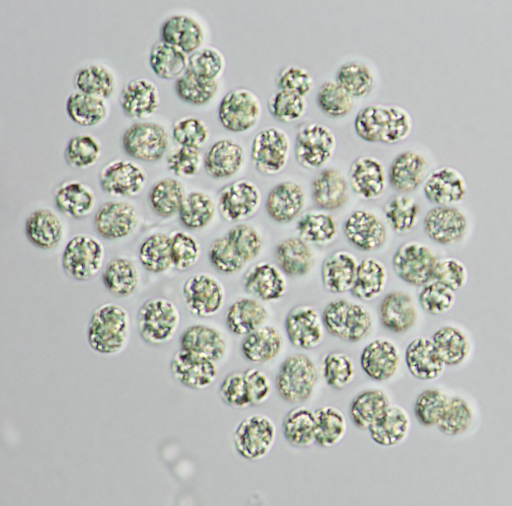

Not all bacteria are lone wolves. Many species will clump together in the millions, forming dense mats—you’ve probably seen them in your shower drain when it’s been a little too long since you last cleaned.

This community-forming ability, called biofilms, is often an essential survival technique. Complex communities can help individual bacteria survive when nutrients are low, and the environment is harsh, or even in the presence of antibiotics. However, these biofilms can be incredibly difficult to get rid of and pose a threat in clinical settings.

But why and how biofilms are formed is not well understood. New research has shown that some bacteria may form biofilms after detecting the death of the bacteria around them.

Bacteria are constantly threatened by viruses called phages, which can infect and break open bacteria cells. Among the many other things biofilms protect bacteria from, they also offer excellent protection against phage attacks.

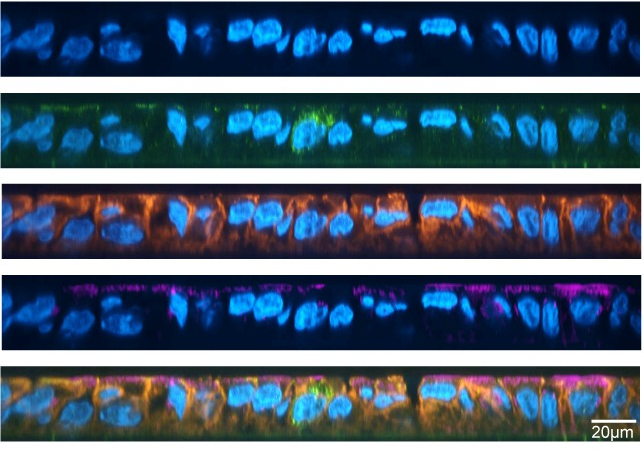

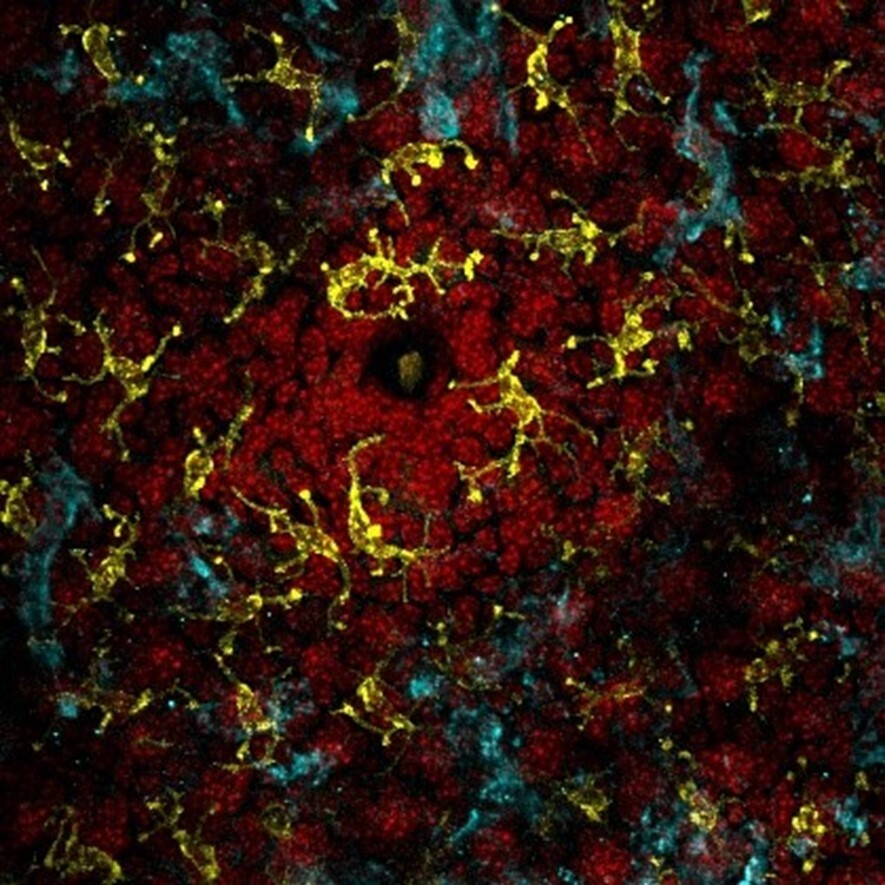

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University looked at how the bacteria Vibrio cholerae responded to lytic phages (more about lytic phages in this article). When the bacteria were exposed to the phages, while they initially experienced several hours of cell death, the surviving members formed biofilm-like structures. Researchers confirmed that these structures were true biofilms by verifying the gene expression of a specific sugar commonly found in biofilms.

While bacteria on the outside of the film were susceptible to phage infection, the bacteria lucky enough to be on the inside were shielded, meaning that the bacteria form biofilms to protect themselves from phage activity.

But how the bacteria knew phages were around was still unclear. Researchers theorized that the bacteria may be able to sense the phages themselves or could sense bacterial death around them. To narrow down what exactly the bacteria were responding to in order to form biofilms, the researchers introduced cell lysate (bacteria that have died and broken open) to the healthy bacteria.

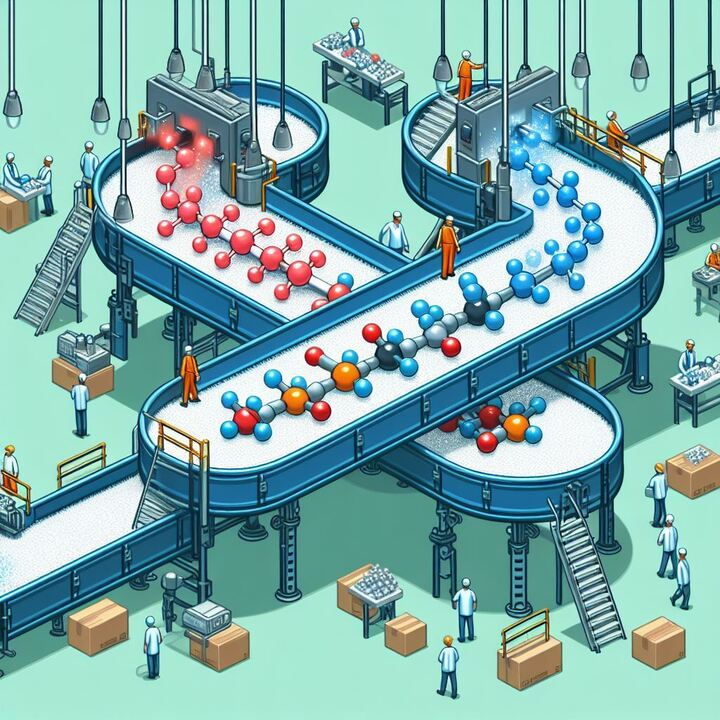

Bacteria exposed to cell lysate increased their biofilm production without phages. The bacteria weren’t responding to the phages directly but instead the death of their fellow bacteria. But what exactly in the dead bacteria cell lysate was queuing biofilm production? Researchers first looked at a molecule called polyamine norspermidine as a candidate. This molecule is plentiful within Vibrio cholerae but is not secreted outside the bacteria, so it can only be sensed once a bacteria breaks open.

To test whether polyamine norspermidine was the instigator for biofilm development, researchers developed bacteria unable to produce the molecule. When these bacterial cells were lysed and exposed to the living bacteria, biofilm production did not occur.

So, they figured out what molecule the bacteria were responding to, but the researchers next wanted to look at how the living bacteria were sensing that molecule. Previous studies have shown that a receptor called MbaA is responsible for regulating biofilm formation in response to norspermidine.

To determine if the MbaA receptor was also required for biofilm formation in the presence of lysed cells, they used a bacteria strain with an MbaA that doesn’t work. When these bacteria were exposed to the deal bacteria cell lysate, biofilm production did not occur. Meaning that both the molecule norspermidine and the receptor MbaA were responsible for inducing biofilm formation.

To verify that biofilm formation actually protected bacteria in the presence of phages, researchers looked at survival rates between their normal bacteria and their mutant bacteria, which either had a mutated MbaA or were unable to produce polyamine norspermidine.

While the normal bacteria were able to recover their populations after being exposed to phages, the non-biofilm-forming mutant bacteria showed lower survival rates.

But can detecting cell lysis protect bacteria from other threats?

Some bacteria have the ability to secrete a toxin into the bacteria around them, often deemed as a molecular syringe. The toxin results in cell lysis for the unfortunate bacteria on the receiving end.

To determine whether this type of cell lysis could be protected against by biofilm formation, the researchers introduced their healthy bacteria and their mutant bacteria to Acinetobacter baylyi, a bacterium that contains the molecular syringe. Only when the healthy bacteria were first treated with polyamine norspermidine did they show increased survival compared to the mutant bacteria, meaning that the lysis activity of Acinetobacter baylyi may be too fast-acting for biofilm production to occur. However, the protection provided by the pre-treatment of polyamine norspermidine does indicate that biofilm formation protects bacteria from different kinds of lysis.

Bacteria face many different threats during their lifetime, and how they change their lifestyle to protect themselves from these threats remains largely unknown. However, this research has determined an important piece of the puzzle – some bacteria are able to sense death and respond accordingly.

Link to the original post: Prentice, J.A., van de Weerd, R. & Bridges, A.A. Cell-lysis sensing drives biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Nat Commun 15, 2018 (2024).

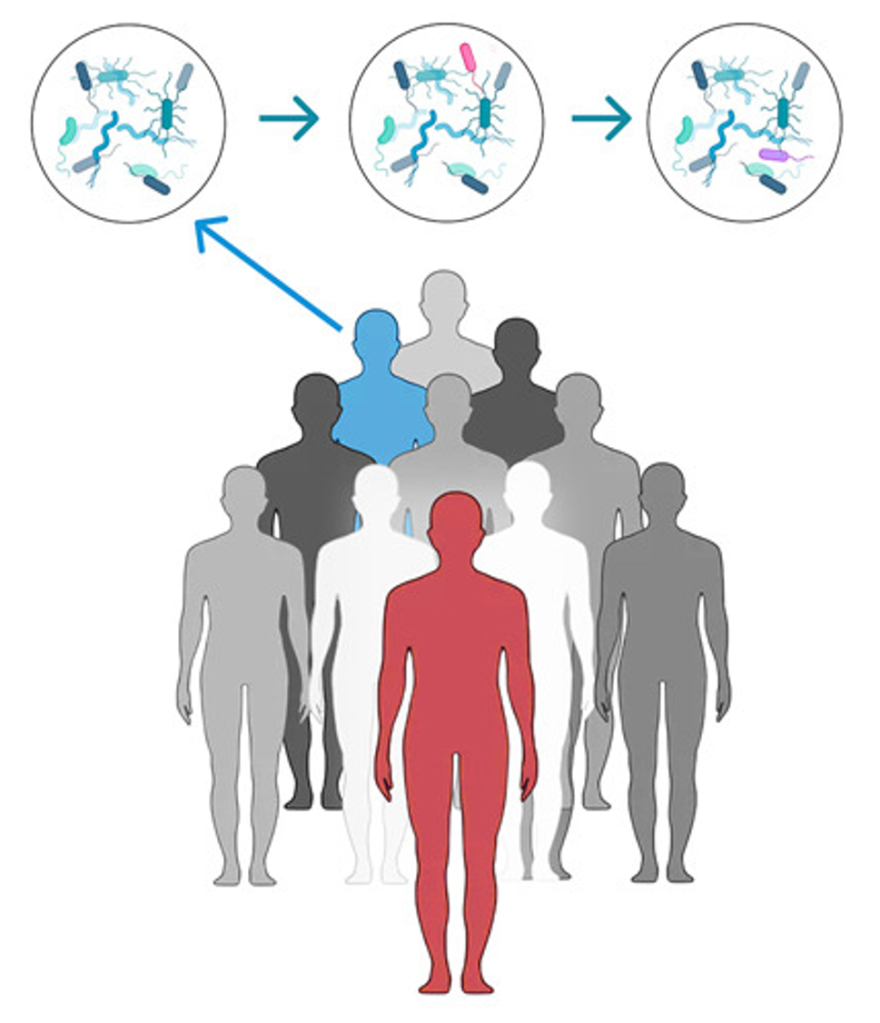

Featured image: Image made by the author with Canva.com