Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Baking Better Bread

While the direct origins of bread-making are still unknown, evidence as far back as Neolithic Asia 14,400 years ago has shown humans baking bread. The natural leavening of bread relied on the fermentation process of microorganisms, though this was unknown at the time. Today, naturally fermented sourdough bread is still made at the industrial, artisan, and home-baking levels.1

Within a sourdough starter lies a microscopic world, filled with microorganisms that can influence and interact with each other in a variety of different ways. In the water-flour mixture, lactic acid bacteria and yeast grow, eating provided carbohydrates in order to give themselves energy. The digestion of these carbohydrates through fermentation leads to the production of carbon dioxide, ethanol, esters, and other organic compounds, unintended byproducts that are pivotal for bread-making. The yeast are primarily responsible for producing carbon dioxide, which causes the dough to rise. The bacteria, on the other hand, primarily influence the starter’s acidity and produce the organic compounds that affect taste and other properties of the dough.1

While there are four types of sourdough starters, this study focuses on Type II.1 Type II sourdough starters are used in industrial settings, allowing for fast, controllable, and large-scale production.2 These starters involve adding specific bacteria and yeast strains that will outcompete any of the naturally present microorganisms to give the dough a specific flavor profile, crumb texture, and a longer shelf life. These starters tend to be more acidic, favoring bacterial production of organic compounds.1 By knowing exactly what bacteria/yeast mixed-strain cultures develop different desired sourdough characteristics, novel sourdoughs can be produced by simply choosing the best pair of bacteria and yeast to use in the starter. However, the bread industry currently has no standardized approach to using sourdough starters, which can thus result in drastically different baked good products in terms of development, maintenance, quality, taste, and volume.1

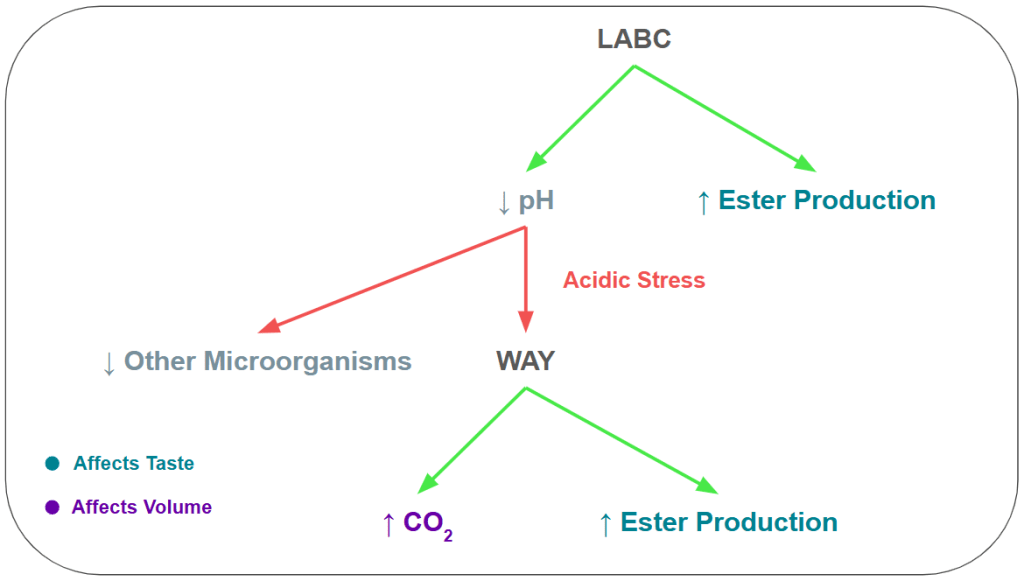

In this study, Pradal and their team investigated a chosen lactic acid bacteria strain, Companilactobacillus crustorum LMG 23699 (LABC), and yeast strain, Wickerhamomyces anomalus IMDO 010110 (WAY), as a potential novel mixed-strain sourdough starter culture. They sought to characterize the interactions and byproducts of these strains within sourdough starters when cultured alone (monoculture) and together (coculture).

In both the monocultures and the coculture, high concentrations of the esters ethyl acetate and ethyl lactate were produced. Ethyl acetate is known to provide fruity, sweet notes, while ethyl lactate gives a creamy taste.3 Acetoin, which provides a buttery taste, was also produced in each fermentation process; however, it was produced in much larger concentrations in the coculture than in the monocultures. This implies that the interactions between LABC and WAY may encourage the production of this organic compound.

The coculture also produced more carbon dioxide than the monocultures, as long as the growth medium did not contain precursors for the building of esters. This higher carbon dioxide production would likely give these cultures a better leavening capacity.

WAY was shown to be vulnerable to acidic stress, particularly in the presence of LABC as it made lactic acid, but the authors propose that the flour within the sourdough starter might act as a buffer to reduce this vulnerability. They also suggest that the coculture’s ability to quickly drop pH might provide it a competitive advantage to any other background microorganisms within the starter, allowing for more control over the sourdough’s desired characteristics.

The low pH might also play a key role in control of desired sourdough characteristics. WAY was shown to produce phenylacetaldehyde and ethyl acetate (sweet taste), allyl acetate (honey taste), and ethyl pyruvate (caramel and citrus taste) in the coculture, likely in response to acidic stress; this could allow for a unique flavor profile for a sourdough using this mixed-strain starter culture. This acidic stress could also account for the increase in carbon dioxide production in the coculture compared to the WAY monoculture. The authors thus propose LABC and WAY as a novel mixed-strain sourdough starter culture, providing desired bread volumes and unique flavor profiles from both the yeast’s and bacteria’s production of esters.

Sourdough starters provide a unique opportunity to explore a microbial environment and the interactions between the microbial communities within it. By customizing these communities with specifically chosen strains or mixed strains such as LABC and WAY, bakers may be able to select the desired bread textures, flavors, and volumes for their sourdough bread. A far cry from the bread-making of ancient civilizations, this specially-designed “better” bread would be custom-made, right down to its microbiome.

Link to the original post: Pradal I, Kaesemans J, Gettemans T, González-Alonso V, De Vuyst L. Coculture fermentation processes in wheat sourdough simulation media with Companilactobacillus crustorum LMG 23699 and Wickerhamomyces anomalus IMDO 010110 reflect their competitiveness and desirable traits for sourdough and sourdough bread production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2025 Aug 12;0:e01325-25. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01325-25

Additional sources:

- Calvert MD, Madden AA, Nichols LM, Haddad NM, Lahne J, Dunn RR, McKenney EA. A review of sourdough starters: ecology, practices, and sensory quality with applications for baking and recommendations for future research. PeerJ. 2021 May 10;9:e11389. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11389.

- Sinha NK. Handbook of food products manufacturing. West Sacramento (CA): John Wiley and Sons; c2007 [accessed 2025 Aug 26]. https://books.google.com/books?id=mnh6aoI8iF8C&q=.

- Pradal I, Weckx S, De Vuyst L. The production of esters by specific sourdough lactic acid bacteria species is limited by the precursor concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2025 Feb 27;91(3):e02216-24. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02216-24.

Featured image: Created by the author with Clip Studio Paint