Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Iron from red meat protects bacteria against antibiotics

When Francesco Pagano began his master’s research at Brown University, he wasn’t trying to rewrite what we know about antibiotics. He just wanted to make them work better. “I’m allergic to a lot of antibiotics myself,” he says. “So, for people like me, who don’t have a big arsenal of treatment options, finding new ways to make existing drugs more effective really matters.”

That goal led Pagano to research an overlooked player in antibiotic resistance: iron. Iron is an essential nutrient that bacteria use to grow and survive. In his most recent study, the lab tested how different forms of iron affect the efficacy of common antibiotics inside the gut’s complex microbial community. One example of iron they surveyed was hemin, a biologically distinct, heme-bound form of iron, most commonly found in red meat.

What they found was both unexpected and a little unsettling: hemin may actually help some gut bacteria resist antibiotics.

To study this, Pagano and his collaborators at the Rhode Island Hospital used human stool samples to gain a real-world snapshot of the human gut microbiome, as opposed to synthetically defined bacterial cultures made from a few known strains. “Synthetic systems are reproducible, but they don’t fully represent how bacteria behave in the human body,” he added.

Working with real stool samples was necessary to reflect bodily bacterial composition, but also added experimental complexity. “Working with human samples is tricky,” Pagano explains. “We had to freeze the stool to preserve it, but freezing changes the microbial composition. There wasn’t much documentation on how long you can store stool samples without losing the original community.”

Over six months, the team managed to recover about 80% of the microbiome’s original diversity; that’s an impressive result for a study of this kind. Beyond that window, though, recovery rates dropped. “There’s an expiration date on frozen stool,” Pagano joked.

They cultured the microbial communities and exposed them to varying levels of iron and to amoxicillin, a widely used antibiotic. Then they analyzed how the bacteria grew, changed, and survived.

The team originally hypothesized that adding iron would make bacteria more vulnerable to antibiotics. After all, iron fuels bacterial metabolism, and active metabolism should, in theory, make bacteria easier to kill. But instead, the opposite happened; especially when the iron came from hemin.

“Hemin protected certain bacteria, like E. coli and Parasutterella, from being killed by amoxicillin,” Pagano explains. “It wasn’t what we expected at all.” One explanation could be that Hemin may activate specific protective responses in certain gut bacteria that were not triggered by free iron. That would suggest that resistance depends on how iron is sensed and metabolized, not just how much is present.

The finding could have implications for how diet interacts with antibiotic treatment. High consumption of red meat might indirectly promote the survival of gut bacteria that resist antibiotics. “We often see blooms of Proteobacteria, like E. coli, in people who eat more red meat,” says Pagano. “Our study suggests that hemin could be one reason why.”

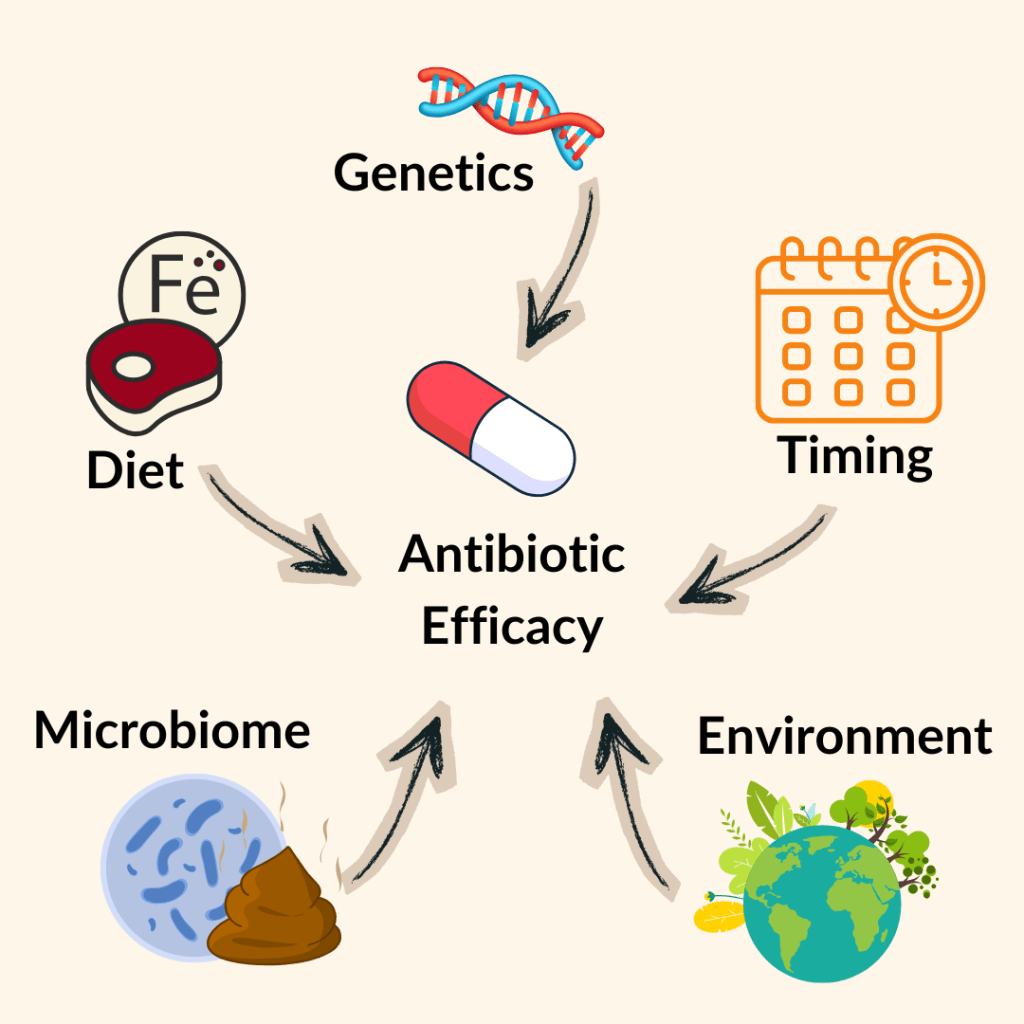

That discovery touches on a larger conversation in microbiome science about how nutrition, medication, and microbial ecology influence one another. Minerals like iron and magnesium, or even supplements, could change how our microbes respond to antibiotics.

Pagano’s path to this discovery was anything but typical. When he joined the Belenky Lab in 2022, he was new to microbiology. “I didn’t know much about microbes at all,” he admits. “It was all so new and different from what I’d studied before.”

Originally unsure whether to pursue a PhD or master’s, he took his advisor’s advice to “just try it.” Balancing his research with lab management duties was challenging. “There’s a lot to juggle: ordering supplies, running experiments, analyzing data,” he says. “But I learned how connected everything is. Even tiny details in microbiology can become crucial later.”

Pagano hopes his work sparks new conversations about personalized medicine. The idea that diet, lifestyle, and even iron intake could one day inform antibiotic prescriptions. “It’s not just about taking the right pill,” he says. “We might eventually pair antibiotics with specific dietary guidelines or supplements that enhance their effect.”

Still, much remains unknown. “We don’t yet understand what’s happening at the transcriptomic level (what genes are being turned on or off),” he says. “There’s a whole layer of metabolic communication happening between the bacteria and the iron that we haven’t mapped yet.”

That unknown keeps him motivated. “We all rely on antibiotics,” he says, “but they don’t work the same for everyone. If diet or iron can make a difference, that’s worth understanding.” What started as a reluctant master’s project ended up uncovering a subtle, potentially powerful connection between diet, microbes, and drug resistance. For Pagano, the lesson is simple: “Broaden your horizons. Sometimes the most unexpected findings are the ones that matter most.”

Link to the original post: Pagano F, Bemis DH, Rehman R, Shapiro JM, Belenky P. Differential impacts of hemin and free iron on amoxicillin susceptibility in ex vivo gut microbial communities. Front Microbiol. 2025 Dec 1;16:1629464. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1629464. PMID: 41403646; PMCID: PMC12702856.

Additional sources

- Py B, Barras F. Building Fe-S proteins: bacterial strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010 Jun;8(6):436-46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2356. PMID: 20467446.

- Celis AI, Relman DA, Huang KC. The impact of iron and heme availability on the healthy human gut microbiome in vivo and in vitro. Cell Chem Biol. 2023 Jan 19;30(1):110-126.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.12.001. Epub 2023 Jan 4. PMID: 36603582; PMCID: PMC9913275.

- Berg G, Rybakova D, Fischer D, Cernava T, Vergès MC, Charles T, Chen X, Cocolin L, Eversole K, Corral GH, Kazou M, Kinkel L, Lange L, Lima N, Loy A, Macklin JA, Maguin E, Mauchline T, McClure R, Mitter B, Ryan M, Sarand I, Smidt H, Schelkle B, Roume H, Kiran GS, Selvin J, Souza RSC, van Overbeek L, Singh BK, Wagner M, Walsh A, Sessitsch A, Schloter M. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome. 2020 Jun 30;8(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0. Erratum in: Microbiome. 2020 Aug 20;8(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00905-x. PMID: 32605663; PMCID: PMC7329523.

- Huttner A., Bielicki J., Clements M. N., Frimodt-Møller N., Muller A. E., Paccaud J. P., et al. (2020). Oral amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid: properties, indications and usage. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.11.028

- Hiol, A., & Veiga, P. (2025). From the Lab to the Plate: How Gut Microbiome Science is Reshaping Our Diet. The Journal of Nutrition.

Featured image: Created by the author using Canva Pro.