Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Novel Antibiotics and Where to Find Them

In the modern day, it is difficult to imagine the true threat of infectious diseases without antibiotics. In 1900, infectious diseases caused 33.3% of all deaths in the United States, whereas in 1997, only 4.5% of all deaths were attributed to infectious diseases.1 Modern medicine relies on the use of antibiotics, not only to be able to treat infectious diseases, but also in medical practices like organ transplants and cancer treatment.2

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a looming threat over the modern medicine we take for granted. More than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur in the United States each year, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths.3 This threat is paired with the slowing of the antibiotic discovery pipeline.

According to a WHO report in 2021, only 12 new antibiotics were approved by the FDA since 2017, and of those 12, only 2 did not have already-known mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance.4 There is a desperate need, then, for the discovery and development of new antibiotics that can overcome these mechanisms of resistance.

Traditionally, new antibiotics have been discovered from bacterial or fungal sources. Within soil ecosystems, microbes wage a war for survival; producing antibiotics that will kill competitors gives certain microbes an advantage. During the Golden Age of antibiotic discovery (1940s through the 1960s), new antibiotics were discovered almost yearly by isolating these antibiotic-producing microbes from soil samples.5 But with the pipeline drying up, scientists have been searching for new sources of antibiotics.

In this study, Torres and their team explored a domain that has been largely ignored for antibiotic discovery: archaea. Structurally similar to bacteria and genetically closer to eukaryotes, archaea are distinctive from both, possessing unique cell membranes, metabolic pathways, and stress-adaptation mechanisms.6 Archaea are most well-known for thriving in environments that would be lethal to most other forms of life, such as extreme heat or cold, high salt solutions, acidic or basic conditions, high oceanic pressures, or even within toxic waste. Many archaea not only grow in these environments but often require these extreme conditions to survive.7 As they have been largely understudied, the researchers looked for potential new antibiotics produced by these microorganisms.

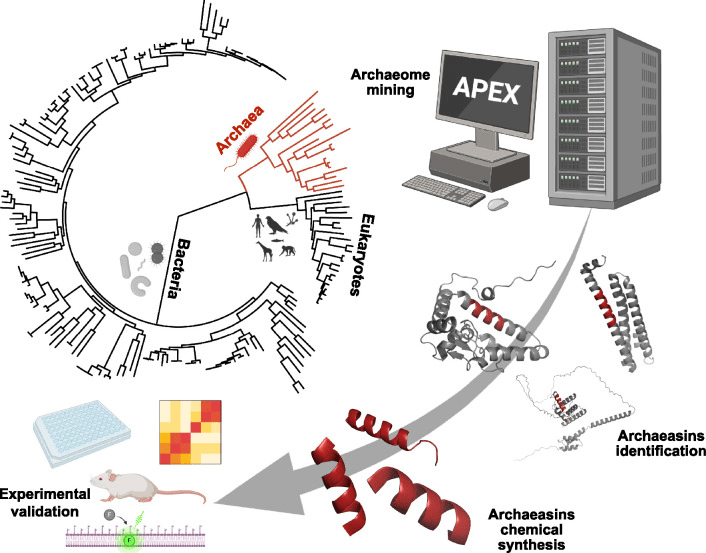

The scientists utilized UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, an online database of high-quality proteomes. A proteome is all of the proteins believed to be expressed by a given organism; this data is a combination of predictions based on the genetic sequences of the organism as well as experimentally identified protein sequences.8 Thus, by searching the available archaeal proteomes, the researchers could identify peptides (short proteins) that might act as antibiotics (Figure 1).

Since proteomes are extremely large, the burden of scouring these sequences was given to the deep learning framework APEX 1.1. Trained on known antimicrobial peptides, APEX 1.1 could identify similar sequence structures in the proteomes as potential new antibiotics; these archaeal peptides with predicted antimicrobial activity were called archaeasins. Overall, APEX 1.1 was able to identify 12,623 archaeasins from 233 archaeal proteomes.

The researchers then artificially synthesized 80 of these archaeasins to test their antimicrobial ability on several bacterial strains, all of which are well-known antibiotic resistant clinical pathogens: Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium. 75 of the 80 (93%) showed antimicrobial activity against at least one of the bacterial strains, indicating APEX 1.1 was successful at correctly identifying archaeasins. In addition, these archaeasins were less than 70% similar in sequence to known antimicrobial peptides, giving them a uniqueness that might allow them to overcome antibiotic resistant strains.

Three archaeasins were then tested for their antibiotic effect in mice. In a skin abscess model, all three archaeasins successfully reduced the bacterial counts; one in particular, Archaeasin-73, reduced the bacterial count as well as polymyxin B and better than levofloxacin, two known antibiotics.

In addition, there was no observation of toxic effects of the archaeasins to the mice. Since antibiotics need to both be effective at stopping bacterial growth and safe to the patient, this is an important indicator for selecting potential future antibiotics.

There is a desperate need for new antibiotics to keep up with the growth of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. These researchers show that archaea might provide a new source for these needed antibiotics, as well as a way to rapidly analyze and predict antibiotic peptides within their proteomes. Future research could train the deep learning framework to not only look at the protein sequence, but to predict the three-dimensional structure of the final peptide, which could increase the model’s accuracy when predicting antimicrobial activity.

With a new domain to explore for antibiotic activity and a quick, automated process to do so, the antibiotic discovery pipeline may be able to catch up to the growing tide of antibiotic-resistant bacteria before history repeats itself.

Link to the original post: Torres MDT, Wan F, de la Fuente-Nunez C. Deep learning reveals antibiotics in the archaeal proteome. Nat Microbiol. 2025;10:2153-2167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02061-0.

Featured image: Created by the author with Clip Studio Paint