Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

How Bile Acids Neutralize a Deadly Gut Toxin

Antibiotics save lives, but sometimes they leave destruction in their wake. Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill bacteria indiscriminately, stripping away the diverse microbial community and leaving the gut vulnerable. For approximately half a million people each year in the United States alone, a routine course of antibiotics creates an opening for a life-threatening Clostridiodes difficile infection.

C. difficile is an opportunistic pathogen that thrives when the gut microbiome is weakened. Once established, C. difficile releases a potent toxin called TcdB that erodes the gut lining and triggers intense inflammation, diarrhea, and colitis.

Current treatment options are limited, and the standard-of-care relies on more antibiotics, which counterintuitively increase the risk of recurrent infection. Thankfully, a team of researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto discovered a new way to neutralize TcdB: using bile acids to lock it into a harmless state. Bile acids are steroid-derived molecules that help digest dietary fats and can be chemically altered by gut microbes. Some support C. difficile growth, while others suppress it.

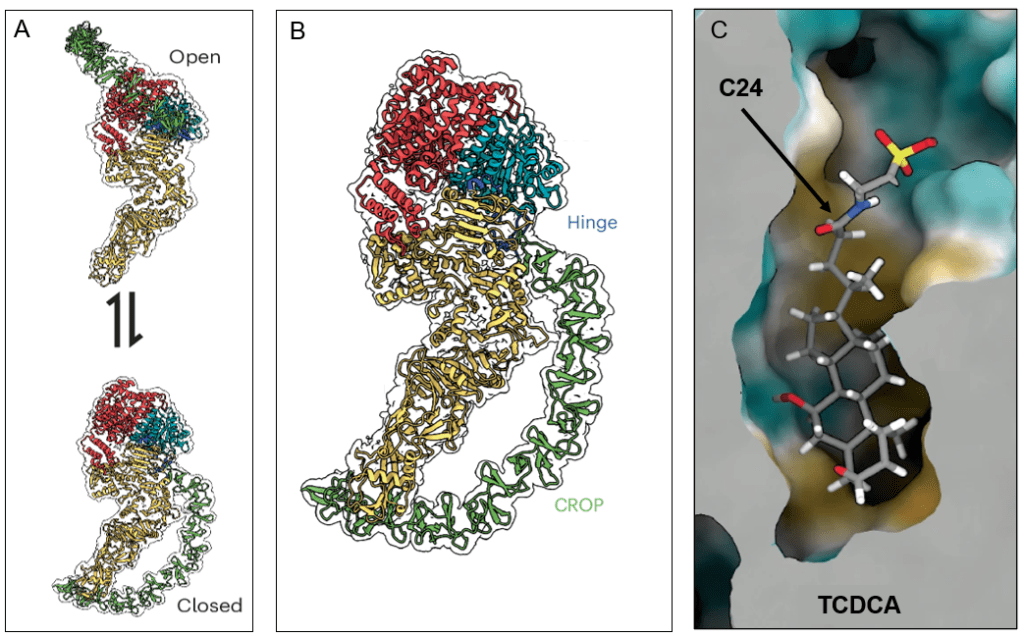

The key to understanding the underlying mechanism of neutralization by bile acids is TcdB’s structure. TcdB exerts its toxic effects by forming pores across the membranes of infected cells, causing fluid leakage and cell death. At one end lies the combined repetitive oligopeptide (CROP) domain, a flexible, retractable arm that can swing between open and closed conformations in response to environmental conditions. In its open conformation, the CROP domain extends outward and exposes receptor-binding surfaces. In its closed conformation, it folds back on itself to shield those surfaces.

Using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), the authors confirmed that TcdB naturally switches between open and closed states. This balance is crucial because only the open conformation can bind host receptors and trigger TcdB’s toxic effects.

Previous work had uncovered small molecule bile acids that interfered with TcdB, but the mechanism of action was unclear. In this new study, the researchers focused on two bile acids that had been shown to inhibit TcdB-mediated damage: Taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA) and cholic acid methyl ester (CA-methyl). When the team incubated TcdB with these bile acids and imaged the complexes using cryo-EM, almost all toxin molecules were observed in the closed conformation. The bile acids were interacting with TcdB by locking it shut, forcing it into its closed, inactive conformation.

Closer inspection revealed that the bile acids nested inside a small, deep, and highly hydrophobic pocket at the junction between three major domains (shown in the figure in red, cyan, and yellow). This pocket anchors the CROP hinge and determines whether it appears open or closed. By binding the pocket, bile acids TCDCA and CA-methyl stabilize the closed conformation, preventing the CROP arm from extending. These structural insights explain several long-standing observations: bile acids only inhibit TcdB only when the CROP domain is closed, and toxins lacking the CROP terminus are resistant.

Armed with a structural map of this pocket, the researchers turned to therapeutic design. There is only one issue: natural bile acids are reabsorbed by the small intestine and recycled to the liver. Absorption is undesirable for a successful inhibitor because TcdB acts in the gut, so it needs to stay where the toxin is active. The team focused on carbon position C24, the one position on the bile acid scaffold that protrudes from the TcdB pocket and tolerates chemical modification.

By affixing large, highly polar kinetophores to C24, they created new derivatives too bulky and hydrophilic to cross the intestinal wall. These engineered molecules, dubbed synthetic bile acids (sBA), retained the ability to bind TcdB. sBA-2 stood out as both potent and non-toxic. When administered orally to mice, it remained almost entirely within the gut; none was detectable in the bloodstream even 24 hours after dosing.

Next was to test whether sBA-2 could protect mice from disease. The researchers treated antibiotic-disrupted mice with daily doses of sBA-2 before and after exposing them to bacterial spores. The results were striking: treated mice lost less weight, showed reduced clinical signs of disease, carried a lower bacterial burden, had markedly heather tissue, and demonstrated improved overall survival. Notably, sBA-2 did not directly kill C. difficile or block spore germination. Its protective ability came exclusively from neutralizing the toxin, not from further disturbing the microbiome, which is a crucial advantage over traditional antibiotics.

Since sBA-2 works by locking the toxin into its closed conformation, it may avoid the pitfall of traditional antibiotic treatments with recurring infections. Preliminary data suggests it may even synergize with existing antibody therapies, like bezlotoxumab. The authors note that future versions of sBAs could potentially modulate immune receptors like TGR5, adding anti-inflammatory benefits. With C. difficile infections still among the most common and costly healthcare-associated diseases, innovations like sBA antitoxins offer a compelling glimpse into the next generation of antimicrobials. Ones that disarm pathogens not by killing them, but by locking the hinges of their most dangerous weapons.

Link to the original post: Miletic, S.; Icho, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Structure-guided design of a synthetic bile acid that inhibits Clostridiodes difficile TcdB toxin. Nat. Microbiol. 2025. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-025-02179-1.

Featured image: Generated using ChatGPT, based on US Centers for Disease Control