Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Security hacked: How phages slip past bacterial defenses

Keeping phages at bay

Bacteria live under constant threat from phages (short for bacteriophages). These viruses’ main purpose is to find a suitable bacterium, turn it into a factory for making new phages, and ultimately kill the host once their work is done. To survive, bacteria must build strong security systems to keep these viral invaders out.

Bacteria rely on a remarkable diversity of defense systems capable of stopping phages at different stages. For example, once a phage injects its DNA into a bacterium, defense systems such as restriction-modification and CRISPR-Cas can recognize and cut the viral DNA at specific sites, preventing the phage from taking control. Other defenses act when the virus has already begun replicating in the host by interfering with the production of viral proteins, or preventing these proteins from assembling into new viruses1.

More than 250 defense systems are currently known, and for many of them their exact mode of action is unknown2. Bacteria carry several of these systems at once, creating multiple layers of protection that may even work together (as we saw in the previous article). This helps the bacteria maximize their chances of clearing viral threats and lets them carry on with a peaceful, phage-free life.

Here come the break-in specialists

With all these defense systems, bacteria resemble a heavily secured bank equipped with alarms, surveillance cameras, and reinforced vaults.This is usually enough to discourage most intruders,but not phages. These viruses have evolved a range of clever strategies to slip past bacterial defenses and launch a successful infection. One of these strategies involves specific proteins, called anti-defense proteins, that can neutralize bacterial defense systems. Most anti-defense proteins are specific, meaning they can disable only one system or a few closely related ones. As a result, phages may need to carry several anti-defense proteins to counter different defenses.

Uncovering the anti-defense toolbox of phages infecting Pseudomonas

In this study, researchers investigate anti-defense proteins in phages that infect the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. They compared the genomes of over 150 phages, focusing on a region where the gene content varies between phages. The idea is that defense systems are diverse and no single phage can carry all the anti-defense proteins needed to overcome every bacterial defense. Instead, each phage carries only a subset of these proteins, creating a highly variable region in its genome that is shaped by the types of defenses it encounters in different bacteria.

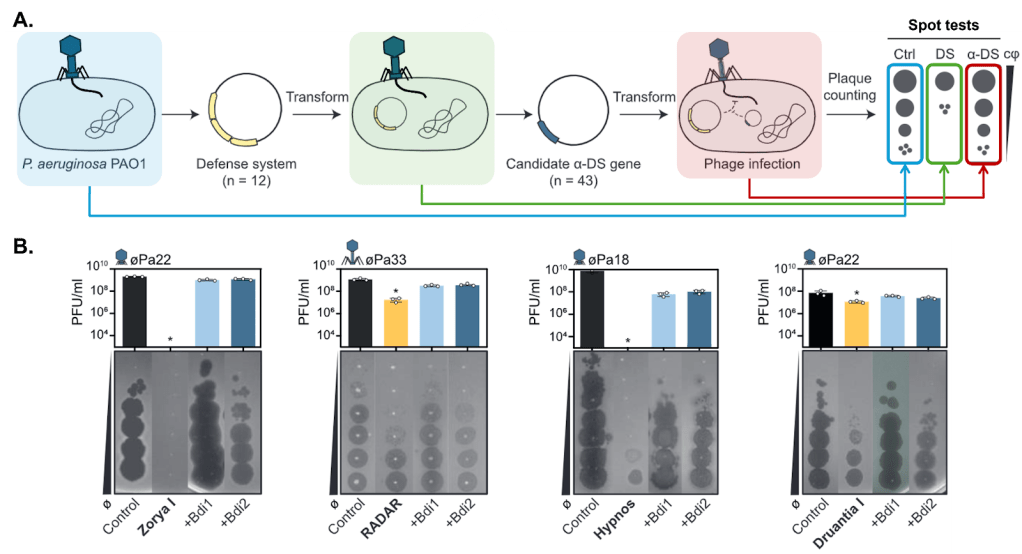

From this initial analysis, the team selected 43 candidate proteins and tested them against 12 different bacterial defense systems to see if they could restore phage infectivity. Here’s how the experiment works (Figure 1A): First, the authors equipped a lab strain of P. aeruginosa with a specific defense system, such as Zorya3.

They then measure the system’s effectiveness using a spot test, a common experiment used to measure phage growth. If the defense system works, fewer phages are produced. Next, they introduce one of their candidate anti-defense proteins. If the protein works as an anti-defense, it neutralizes the defense system, allowing the phage to replicate normally. In spot tests, this appears as a restoration in the number of phages produced.

Overall, they identified five new anti-defense proteins. Three of these behaved as typical anti-defense proteins that target a single defense system: ZadI-1 blocked Zorya type I, TadIII-1 inhibited Thoeris type III, and DadIII-1 countered Druantia type III. No anti-defense proteins had previously been reported for these systems. Interestingly, they also discovered two broad-spectrum anti-defense proteins, Bdi1 and Bdi2, each capable of inhibiting four different defense systems (Figure 1B).

The inhibited defense systems all act by targeting phage nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) but further investigation is still needed to uncover the exact mechanism of inhibition. Using predicted structures of Bdi1 and Bdi2, they showed that these anti-defense proteins are also found in other phages infecting a diverse array of different bacteria.

Complete analysis of known anti-defense proteins in the phage genus Pbunavirus revealed that they can encode up to five anti-defense proteins which enable the neutralization of up to seven distinct defense systems, numbers that are expected to increase as novel anti-defense proteins are being uncovered.

And on the practical side?

Like many bacteria, P. aeruginosa is becoming increasingly difficult to treat because of antibiotic resistance, and phages are emerging as a promising alternative. Phages from the Pbunavirus genus investigated in this study are especially interesting for phage therapy, as they have already shown encouraging results in clinical trials4. By knowing which proteins allow phages to bypass bacterial defenses, researchers could design phages equipped with extra tools to overcome those barriers and ultimately contribute to the development of more effective phage-based treatments.

Link to the original post: Costa, A. R., van den Berg, D. F., Esser, J. Q., van den Bossche, H., Pozhydaieva, N., Kalogeropoulos, K., & Brouns, S. J. (2025). Bacteriophage genomes encode both broad and specific counter-defense repertoires to overcome bacterial defense systems. Cell host & microbe, 33(7), 1161-1172. link

References

Featured image: (Created by the author using ChatGPT)