Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

All in Our Heads or Right in Our Noses?

An inescapable black hole in the center of your chest, a darkness you can’t seem to crawl out of, a parasite that drains your energy and your happiness, leaving you feeling weak, sad, and lonely; to millions of Americans, depression is a weighted shackle they cannot find the key to. Characterized by a persistent feeling of sadness and emptiness, depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide.1, 2

In 2021, approximately 14.5 million adults in the United States were reported to have had at least one major depressive episode. This number is believed to be heavily underestimated; many people with depression do not seek medical help.2, 3 Women have a higher risk of developing depression than men, and depression is most prevalent in 18- to 29-year olds.2 Despite its prevalence, the underlying causes of depression are unclear and complex, making treatment difficult and often unsuccessful.1, 2 Therefore, the mechanisms of depression must be further researched in order to design more efficient treatments.

The availability of certain nervous system signaling molecules, called neurotransmitters, are likely part of the underlying cause of depressive symptoms. Because of this, several medications for depression increase the presence or longevity of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the central nervous system to combat depressive symptoms.2 One natural regulator of neurotransmitter release are steroid sex hormones like testosterone (primary male sex hormone) and estradiol (primary female sex hormone). These hormones regulate the synthesis of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, and they have been shown to have a powerful role in depression, particularly in women.4

Recent evidence has shown how the gut microbiome, that is, the microorganisms that line the digestive tract, influences brain function. However, other microbiomes, like the nasal microbiome, have not been as studied. The nasal system is unique in that it allows direct entry of drugs to the brain. Thus, compounds synthesized by nasal microorganisms might reach the brain and influence its function. In this study, Xiang and their group investigated the potential influence of nasal bacteria on depression and the potential mechanisms and interactions involved.

When comparing the nasal microbiota of healthy patients and patients with untreated depression, the researchers found Staphylococcus aureus was the most abundant species in patients with depression. S. aureus, while known to be a dangerous bacterial pathogen, is also a known member of the normal human skin microbiome, and in about 30% of the human population, S. aureus resides in the nose as part of the normal nasal microbiome too.5

In this study, the researchers transplanted the nasal microbiota from healthy individuals and patients with depression into mice models. Strikingly, the mice that received transplants from depressed patients showed increased anxious and depressive behavior. Considering how common S. aureus was in patients with depression, the team colonized the noses of mice models with S. aureus or with Staphylococcus epidermis, a close relative of S. aureus and another natural bacteria in the nose. Female mice had more anxious and depressive behavior when given S. aureus compared to S. epidermis; male mice showed similar results only after they were exposed to long-term, unpredictable mild stress. This suggested that the effect S. aureus has on depression is more pronounced in females, which aligns with the fact that depression is more common in women than men.2

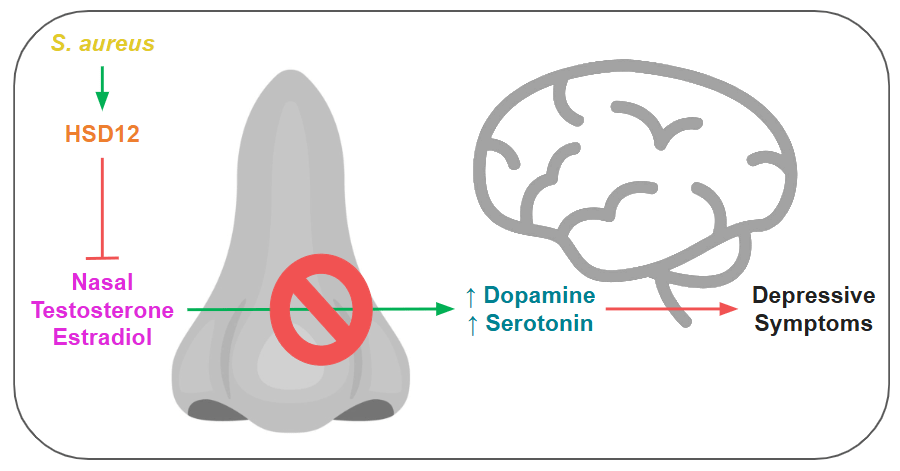

The researchers then identified a unique S. aureus gene that produces the enzyme 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD12), which can break down sex hormones. In depressed individuals, the sex hormones testosterone and estradiol were decreased specifically in the nose, even while these hormones were at normal levels in their bloodstream. In the mice models, mice given S. aureus had similar reduced levels of nasal sex hormones, especially estradiol, compared to mice given S. epidermis. In addition, the S. aureus-colonized mice also had lower levels of serotonin and dopamine in the brain, whereas other neurotransmitters with no link to depression were not affected. Notably, when the team mutated the HSD12 gene in S. aureus, the mice presented behaviors indistinguishable from the healthy control mice, suggesting a powerful link between S. aureus and emotional health.

S. aureus colonization in the nose, even in a normal nasal microbiome, may pose a greater risk on the incidence of depression, particularly in females. The HSD12 gene allows nasal S. aureus to break down the steroid sex hormones testosterone and estradiol, decreasing their abundance in the nose. Since these hormones increase dopamine and serotonin in the midbrain, and given the direct link between the nasal cavity and the brain, these decreased sex hormone levels could lead to reduced production of these neurotransmitters, resulting in depressive symptoms (Figure 1).

Further research could potentially identify a correlation between the population of humans with nasal S. aureus and the population of humans that have developed depression. This could also open up a pathway of novel treatments for depression adjusting not the human brain’s chemical signals, but the nasal bacteria’s influence on these signals.

Link to the original post: Xiang G, Wang Y, Ni K, Luo H, Liu Q, Song Y, Miao P, He L, Jian Y, Yang Z, et al. Nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage promotes depressive behavior in mice via sex hormone degradation. Nat Microbiol. 2025 Sep;10:2425-2440.

Featured image: Created by the author with Clip Studio Paint