Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

How do plants perceive their microbiome?

As many articles on this blog show, microbes play diverse roles in ecosystems, depending on the context. For example, they can be used to make cheese or to balance the gut microbiome, but can also be dangerous when infecting patients receiving bone transplants. How then, can organisms determine whether to fight or welcome the microbes that colonize them? Researchers in Zürich set out to address this question by investigating how plants perceive their microbiome.

To do this, the researchers looked at the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, which is extensively used in research with the expectation that the resulting findings can be extrapolated.

The team identified a set of genes in A. thaliana that is consistently activated when bacteria colonize leaves. They hypothesized that these ‘general non-self response’ (GNSR) genes are a defense adaptation strategy that protects against pathogens. In addition, these genes correlate with the number of microbes that colonized the plant: they were expressed more strongly when more microbes were present.

In the latest study the investigators continued this line of research, but this time they looked at the GNSR genes in relation to the non-pathogenic microbiome. Andreas Keppler, the paper’s main author, shares his insights about plant immunity and work in a plant microbiology lab.

Perceiving the non-self

“These [GNSR] genes were not newly discovered,” explains Andreas, “but grouping them as a consistent response to non-self signals was a novel insight. The idea is that the plant perceives non-self signals, be it from pathogens or commensals and there is a basal response to this perception that includes these genes. The first study focused on pathogenic interactions, while the latest work explores how GNSR genes affect the non-pathogenic microbiota.”

The importance of doing your own research

Early in the project, the team encountered some confusion about whether the GNSR represented a truly novel immune response.

“I had just started my PhD when I joined the project,” recalls Andreas. “Our lab had been in contact with collaborators, who had identified gene sets in Arabidopsis that are activated by various bacterial molecules. We thought we had already checked for overlap between their genes and ours—but apparently, the former collaborators had misunderstood each other during that comparison.”

As a result, Andreas was tasked with investigating how the GNSR differed from previously described immune responses. “We spent a lot of time trying to make sense of this supposed difference, but it never quite added up. Still, I was new to the lab and simply trusted that the groundwork had been done.”

Eventually, Andreas decided to revisit the data and found significant overlap between the GNSR and known immune responses. Rather than seeing this as a setback, Andreas viewed it as part of the scientific process.

“This made me realize the importance of verifying assumptions and doing your own analyses, sometimes even if you think it’s already been done.”

Cooperative experiments

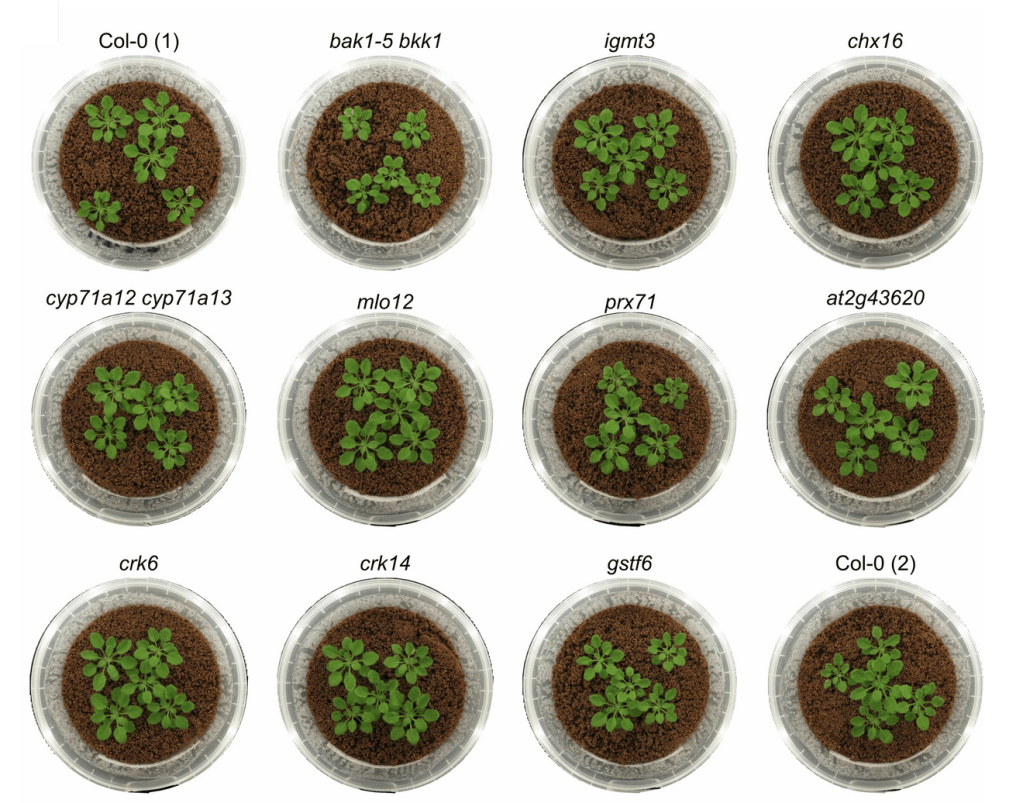

To look at the interactions between A. thaliana, its GNSR genes and the microbiome, the researchers grew thousands of little plants in the lab.

“We have nice growth systems to culture plants under sterile conditions and to inoculate them with specific leaf bacteria or defined bacterial communities. We also use different mutant plant lines, all in a very controlled setting.

Since the biological systems are complex, you need a lot of plants to draw conclusions from statistical analyses. And since plants take time to grow and you don’t know what’s going to happen in your experiment, we also try a lot of experiments in parallel. During the revisions for the paper, we grew, inoculated and harvested around 2500 plants.”

Luckily, Andreas didn’t have to work alone. “We always collaborate: when we harvest plants for experiments where we test a lot of conditions in parallel, it’s two people cutting plants, two people processing samples and one person running around and doing measurements. This takes more or less the full day for around 400 to 600 plants. The lab is a great place to work because we collaborate all the time!”

Understanding plant health

Understanding how healthy plants interact with their microbiome is important for the future of agriculture. Andreas explains that a lot of the knowledge about plant-bacteria interactions comes from studies that looked at pathogens and how they cause disease. “This research was super important and brought us to where we are today; we’re at a point where we’re realizing that this is one part of the story. To engineer microbiomes for application in agriculture, we need the other half, which is understanding what constitutes a healthy system. We’re trying to characterize on a molecular level what a healthy system looks like.”

Rigorous validation is needed

Andreas invites researchers from other labs to repeat the experiments and make sure that his findings hold true under variable circumstances. “It’s cool to see that this study has attracted more attention than I expected, but I hope that it also attracts curious criticism. In fact, a paper published a few months after ours reproduced one of our results, and that was very encouraging! These systems tend to be very complex and a bit artificial so it’s good to have rigorous validation.”

Link to the original post: Keppler, A., Roulier, M., Pfeilmeier, S. et al. Plant microbiota feedbacks through dose-responsive expression of general non-self response genes. Nat. Plants 11, 74–89 (2025).

Featured image: Keppler et al. 2025