Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

When Microbes Become Master Chocolatiers

Everyone loves chocolate. Countries such as Trinidad, Ecuador, and Madagascar are renowned for producing fine-flavor cacao, distinguished by fruity, floral, and nutty notes. In contrast, bulk cacao is used mainly for mass-market chocolate and has a simpler, more bitter taste. The secret that separates fine from ordinary isn’t solely in the bean, but lies in fermentation: a well-fermented cocoa bean develops a rich, layered, and complex flavor, whereas an under-fermented bean lacks depth. It’s the microbes behind the magic, driving fermentation and shaping fine chocolate flavor.

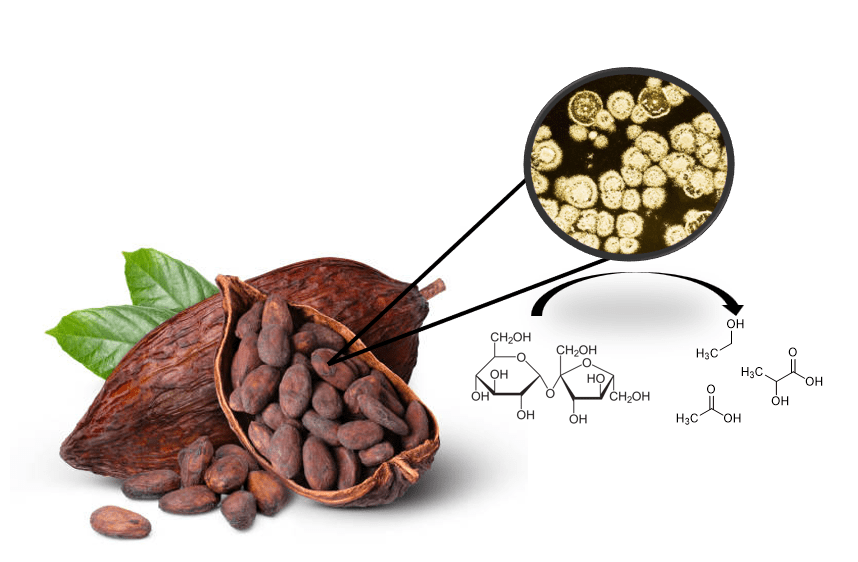

After harvest, cocoa beans are piled into wooden boxes, baskets, or heaps and left to ferment. While seemingly a straightforward farm practice, fermentation is actually a sophisticated microbial process. Microbes in the pulp – yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, and acetic acid bacteria – consume sugars and release acids and alcohols. These chemical reactions transform the beans’ pulp, laying the foundation that later roasting will develop into the aromas and flavors we associate with chocolate. Each fermentation is shaped by its own microbial “signature.” The local environment, climate, and handling influence which microbes dominate, ultimately dictating the taste.

On most farms, fermentation happens naturally without any human intervention. That spontaneity creates distinctive regional flavor profiles, but also unpredictability. Flavor outcomes can vary widely from batch to batch, making it difficult to guarantee consistent, fine-flavor chocolate. To address this challenge, Gopaulchan, D. and coworkers asked how microbial composition and environmental factors guide cocoa bean fermentation toward desirable flavor.

The research team observed that as fermentation progressed, temperature rose steadily while pulp pH dropped due to acidification. Importantly, these shifts correlated with visible bean color, a common marker farmers use to decide when fermentation is complete. Temperature and pH were a more precise indicator of the underlying microbial chemistry.

Using whole-genome sequencing, the researchers mapped the microbial community across the entire fermentation timeline. At the start, a variety of microbes were present. As fermentation progressed and the conditions changed, diversity narrowed and a few key species dominated. The most prevalent microbes were bacteria from the Acetobacteraceae family, as used in vinegar production, and yeasts from the Saccharomycotina group, familiar from beer and bread fermentation. The changing environment and microbial population reinforced one another: microbes altered the bean environment (temperature and pH), and those shifts, in turn, selected for the microbes best suited to thrive.

Can this natural, spontaneous process be reliably recreated in the laboratory? Drawing inspiration from sourdough, beer, and cheese, all of which rely on defined starter cultures, the researchers designed a defined microbial consortia. Such a consortium is a curated community of diverse microorganisms, like bacteria and yeasts, chosen to work together to conduct chemical reactions that no single species could manage alone.

The team selected their microbial consortia based on strains and conditions identified in successful spontaneous fermentations. When introduced into controlled fermentation settings, the microbial starter reliably reproduced the hallmarks of fine chocolate fermentation. Even more importantly, the outcomes were reproducible and tunable, meaning fermentation could be steered toward consistent, high-quality results.

For farmers, this approach offers greater control over fermentation, reduces waste, and increases the value of their crops. For chocolate makers and consumers, it promises reliable fine flavors without sacrificing quality to variability. More broadly, this study highlights the growing potential to treat microbial communities as engineerable systems. Just as we define recipes, scientists are shaping microbial ecosystems to carry out complex chemistry. Precision fermentation is already transforming beer, bread, and cheese, so why not chocolate?

A sweet conclusion: Next time you savor your favorite chocolate bar, remember to thank the community of microbial chocolatiers that shaped its flavor.

Link to the original post: Gopaulchan, D.; Moore, C.; Ali, N.; et. al. A defined microbial community reproduces attributes of fine flavour chocolate fermentation. Nat. Microbiol. 2025. Volume 10, 2130-2152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02077-6.

Featured image: Made using stock images of a cacao bean and microbes and in Microsoft PowerPoint.