Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

From Therapy to Threat: Antibiotics and the Resistome

Antibiotics are often hailed as miracle drugs—and rightly so! They’ve saved millions of lives, transforming once-deadly infections into treatable conditions. But as the old saying goes, “every cure comes with a cost”- behind their life-saving success lies a quiet, unintended consequence: collateral damage to our gut microbiome. Every course of antibiotics doesn’t just attack the pathogen; it also strikes at the diverse microbial community living within us—our gut microbiota. This vast ecosystem of bacteria plays essential roles in digestion, immune training, inflammation control, and even mood regulation. Disrupting this community through antibiotic therapy can lead to dysbiosis– a state of microbial imbalance in the gut, where reduced beneficial bacteria and overgrowth of harmful microbes disrupt health, immunity, and digestion due to formation of “leaky gut”– which can set off a cascade of health effects that ripple far beyond our digestive system.

When the Good Bugs Go Missing.

When we take antibiotics to fight off an infection, we’re not just targeting the “bad guys”. We’re also damaging the friendly bacteria in our gut– “the peacekeepers”. These helpful microbes include Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Eubacterium. These “good bacteria” produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), crucial molecules that support the gut lining, reduce inflammation and help regulate the immune system, especially by promoting regulatory T cells (Tregs) that keep immune responses in check. They help maintain the gut barrier, a sort of “security fence” that keeps harmful substances from leaking into our bloodstream.

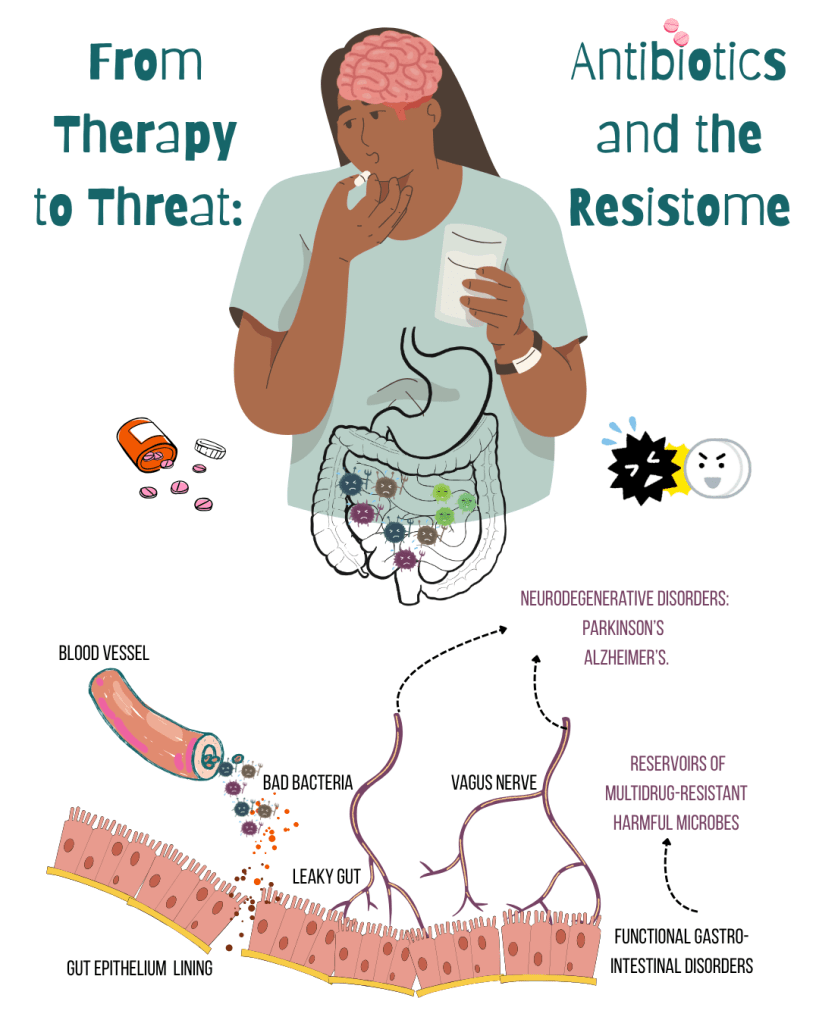

But antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum ones, can’t tell “friend from foe”! Loss of SCFA-producing microbes weakens gut barriers and the gut becomes more permeable—a phenomenon often referred to as a “leaky gut”, allowing a fat-and-sugar molecule from Gram-negative bacteria– lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to enter the bloodstream; triggering chronic inflammation, metabolic disorders & neuroinflammation. As these “good bacteria” decline, harmful and opportunistic organisms—like Clostridioides difficile and enterococci resistant to antibiotic vancomycin—step in to fill the void.

What happens in the gut doesn’t stay in the gut, it echoes throughout the entire body.

The gut isn’t just a digestive organ—it’s wired into our brain via the microbiota–gut–brain axis, a sophisticated communication network involving nerves, hormones, and immune signals. Disruptions in the microbiota–gut–brain axis, often caused by an imbalance in gut bacteria, can affect neurotransmitter synthesis and disturb the gut’s nerve system, which helps control digestion. This long-term microbial imbalances have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Image Source: Antibiotics 2025, 14(4), 371; https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14040371

When Microbes Learn to Fight Back!

Beyond weakening our defenses, antibiotics also arm our enemies. It amplifies the gut resistome—the collection of all antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) present in the microbiome. Through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), ARGs can leap across species! Mobile genetic elements like plasmids and transposons serve as vehicles for this gene-sharing, helping resistance spread rapidly across species.

This genetic exchange becomes especially problematic when beneficial microbes are wiped out. Opportunistic, drug-resistant invaders—such as ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae—fill the vacuum, increasing the risk of fetal infections. Even more troubling is the evidence that early-life exposure to antibiotics can permanently alter the resistome, priming the gut for future dysbiosis and resistance transmission.

Restoring the Microbial Balance!

So how do we begin to repair the damage?

Probiotics (good bacteria in gut) and synbiotics (a combination of probiotics and fibres) are among the first-line interventions—live beneficial bacteria, often paired with prebiotics (fibers that feed them), to reintroduce helpful microbes. While promising, their effects can be variable and strain-specific. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT), a “Microbial Reset Button” in which stool from a healthy donor is introduced into a patient’s gut. FMT has shown high success in treating recurrent C. difficile infections, but comes with challenges in standardization, safety, and regulation.Newer therapies, such as postbiotics—the beneficial metabolites produced by microbes—and engineered bacterial consortia– designed communities of multiple microbial strains, often genetically modified aimed at restoring microbiome balance–like RePOOPulate, offer the benefits of microbiome modulation without introducing live organisms. These approaches reduce risks associated with FMT while maintaining therapeutic efficacy. Precision microbiome therapeutics are customized treatments that use detailed information about a person’s gut microbes to choose the most effective way to support their health. allowing treatments tailored to an individual’s microbial fingerprint and resistance profile, ushering in an era of microbiome-informed medicine.

Written by Pinki

Link to the original post: Cusumano, G.; Flores, G.A.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Impact of Antibiotic Therapy on Intestinal Microbiota: Dysbiosis, Antibiotic Resistance, and Restoration Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 371.

Featured image: Made by the author on canva.