Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

What the Gut’s First Residents Say About Baby’s Brain Health

If you’re a scientist, a parent, or someone who’s ever changed a diaper, you’ve encountered meconium—baby’s first poop. It’s sticky, tarry, and not very glamorous. But according to a new study, it might be doing more than just filling up tiny diapers—it could hold surprising clues about your baby’s brain.

In this pilot study from Brazil’s Rio Birth Cohort, researchers asked: could the microbes in a newborn’s meconium predict how well they’ll do socially just six months later? The team collected meconium samples from 36 newborns and compared them to their developmental progress at 6 months of age, using the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST-II). This test tracks milestones across domains like motor skills, language, and social behavior. Yet, the study’s most interesting connections weren’t about movement or speech—they were about how babies engage socially.

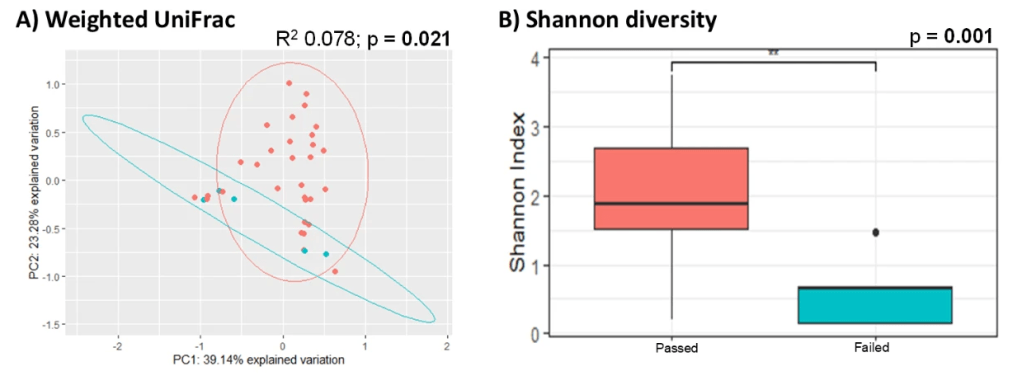

Babies who struggled to meet social-emotional milestones—like smiling, making eye contact, or recognizing familiar faces—also had a very different gut microbiome from day one.

Their meconium showed lower microbial diversity and an overabundance of certain microbial families, including Ruminococcaceae, Christensenellaceae, Roseburia, and Eubacterium—some of which have also been spotted in adults with depression and other mood disorders.

Image source: Naspolini et al. (2025)

The study also looked at what these microbes might be doing (microbial function). Using predictive models of gene function, the researchers found that the microbial community of babies with weaker social skills had reduced functional capacity—meaning fewer genes for producing key molecules like vitamin B12, butyrate, or components of cell walls.

This is a big deal because some of these microbial products help regulate inflammation, energy metabolism, and even neurotransmitter production—those chemical messengers that help the brain think, feel, and interact. In other words, an infant’s gut microbiome may be setting the tone for brain development from day zero.

This study is part of a growing body of research suggesting that the gut microbiome doesn’t just influence digestion—it helps shape our brains and behavior, starting in infancy. What makes this work unique is that it zooms in on the very first gut community—before formula and solid food, which will set the stage for the rest of their life.

And while the study is small (just 36 infants), the findings line up with other research linking early-life microbiome imbalances to later behavioral and emotional issues. Of course, we’re not saying you can diagnose future social challenges from poop alone. But this kind of work opens the door to some fascinating possibilities. Could we one day spot red flags for developmental risk based on a newborn’s microbiome? Could we tweak that microbial mix early on to support better outcomes?

The implications are huge, especially when you consider that factors like C-sections, antibiotics, and maternal health can all shape that first microbial transmission. If we can identify which microbes matter most—and how to support a healthier microbiome—we might have new tools for boosting brain health before babies even babble.

Link to the original post: Naspolini, N.F., Natividade, A.P., Asmus, C.I.F. et al. Early-life gut microbiome is associated with behavioral disorders in the Rio birth cohort. Sci Rep 15, 8674 (2025).

Additional sources

- Frankenburg, W. K., & Dodds, J. B. (1967). The Denver developmental screening test. The Journal of pediatrics, 71(2), 181-191.

- Radjabzadeh, D., Bosch, J. A., Uitterlinden, A. G., Zwinderman, A. H., Ikram, M. A., van Meurs, J. B., … & Amin, N. (2022). Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nature communications, 13(1), 7128.

- Aatsinki, A. K., Lahti, L., Uusitupa, H. M., Munukka, E., Keskitalo, A., Nolvi, S., … & Karlsson, L. (2019). Gut microbiota composition is associated with temperament traits in infants. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 80, 849-858.

- Salvi, P. S., & Cowles, R. A. (2021). Butyrate and the intestinal epithelium: modulation of proliferation and inflammation in homeostasis and disease. Cells, 10(7), 1775.

- Sonali, S., Ray, B., Ahmed Tousif, H., Rathipriya, A. G., Sunanda, T., Mahalakshmi, A. M., … & Song, B. J. (2022). Mechanistic insights into the link between gut dysbiosis and major depression: an extensive review. Cells, 11(8), 1362.

- Mulder, D., Aarts, E., Arias Vasquez, A., & Bloemendaal, M. (2023). A systematic review exploring the association between the human gut microbiota and brain connectivity in health and disease. Molecular psychiatry, 28(12), 5037-5061.

- Sarkar, A., Yoo, J. Y., Valeria Ozorio Dutra, S., Morgan, K. H., & Groer, M. (2021). The association between early-life gut microbiota and long-term health and diseases. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(3), 459.

- Dominguez-Bello, M. G., Costello, E. K., Contreras, M., Magris, M., Hidalgo, G., Fierer, N., & Knight, R. (2010). Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(26), 11971-11975.

- Beier, M. A., Setoguchi, S., Gerhard, T., Roy, J., Koffman, D., Mendhe, D., … & Horton, D. B. (2025). Early childhood antibiotics and chronic pediatric conditions: a retrospective cohort study. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, jiaf191.

- Dominguez-Bello, M. G., Godoy-Vitorino, F., Knight, R., & Blaser, M. J. (2019). Role of the microbiome in human development. Gut, 68(6), 1108-1114.

Featured image: Created by the author using Canva Pro.