Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend

Over the 3.2 billion years they have been around on planet Earth, bacteria have thrived in cramped environments with very little nutrients and resources. To stay ahead of their competitors, many bacteria have employed a number of strategies for fighting off other microbes in their environment. Some bacteria secrete hazardous compounds into their environment that kill off any competitors. Others will alter their environment so that no other organisms can stick to the surfaces they are living on.

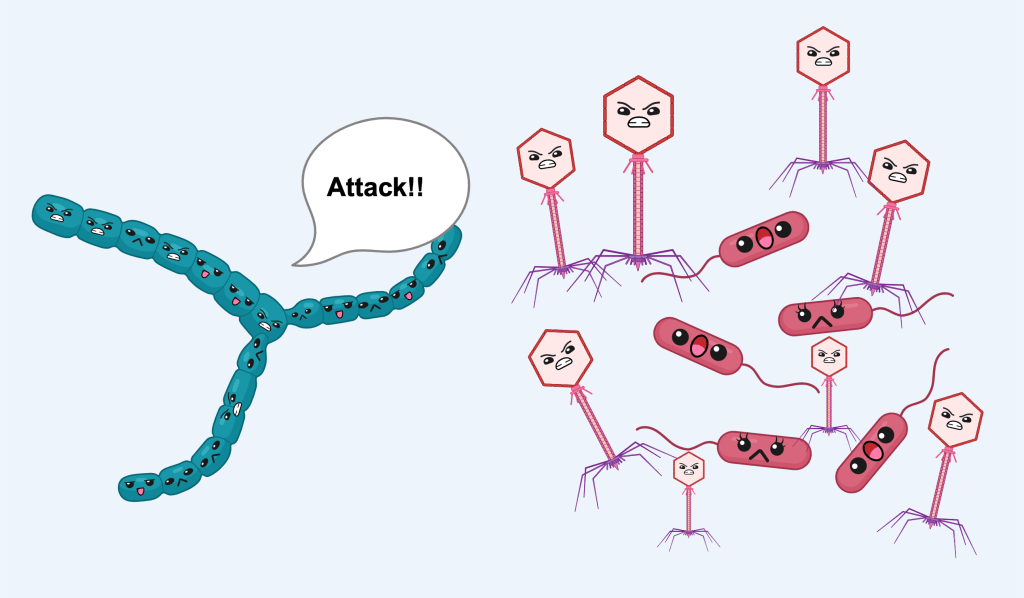

As competing microorganisms gain resistance to these defences, some scientists have wondered if there is another mechanism that bacteria can use for fitness. One theory is that some bacteria will secrete compounds that make other microorganisms more susceptible to predators, such as bacteriophage. The authors of this manuscript analyzed the relationship between various soil bacteria and Bacillus subtilis to identify compounds that might make B. subtilis susceptible to this attack.

Weakening your opponent

The authors utilized a screening technique to identify potential compounds that make B. subtilis more susceptible to bacteriophage infection (Figure). In this screen, the authors plated various colonies of soil-isolated bacteria, allowed them to secrete various metabolites, and analyzed the ability of B. subtilis to grow in the presence of the metabolite and the bacteriophage they were naturally resistant to. Based on this, the authors identified one compound that resulted in larger bacteriophage plaques on B. subtilis, which indicated more infection by the bacteriophage.

This metabolite was secreted by the soil-dwelling Streptomyces sp. 18-5. Streptomyces is a genus of bacteria most commonly known for producing another bacteria-killing substance — antibiotics. To identify the compound that promoted bacteriophage infection in B. subtilis, the authors performed bioactivity-guided fractionation. This experiment identified the metabolite as coelichelin, which is a siderophore, or a small molecule that can bind to iron.

Since coelichelin is a siderophore, the authors investigated if other siderophores could also make B. subtilis more susceptible to bacteriophage infection. Interestingly, the authors found that some siderophores, including ferrichrome and enterobactin, did not affect bacteriophage infection. These siderophores are known to be imported and utilized for growth by B. subtilis, leading the authors to hypothesize that only non-utilized siderophores could affect bacteriophage susceptibility.

To test this hypothesis, the authors used an iron chelator, or a molecule that binds to iron so that it cannot be used by the bacteria. When the chelator was added, B. subtilis was more susceptible to bacteriophage infection. Furthermore, when they inactivated both the chelator and coelichelin with iron sulfate, the bacteriophage could no longer infect B. subtilis. This experiment clearly showed that coelichelin starved B. subtilis of iron, which resulted in higher bacterial killing by the bacteriophage.

A genetic link

B. subtilis is commonly known as a rapid spore-former. Sporulation is important in B. subtilis for protecting the bacteria from starvation. Since coelichelin was linked to iron starvation, the authors investigated the potential role of Spo0A, the main sporulation activator in B. subtilis, in coelichelin-induced bacteriophage sensitivity. When Spo0A was activated, the authors observed less bacteriophage plaque formation, indicating that Spo0A promotes the protection of B. subtilis from bacteriophage infection.

Further analysis of the Spo0A-regulated genes such as sinI, sinR, and abrB, showed that all genes contributed to the bacteriophage susceptibility phenotype. But what about the genes specifically related to sporulation? Interestingly, the authors found that mutations in sporulation genes (spolIAA, sigF, and spolIE) were just as susceptible to bacteriophage infection as the wild type. This means that sporulation caused by Spo0A is not necessary for the observed bacteriophage infection.

To figure out what Spo0A-regulated pathway was important for this process, the authors then analyzed the effects of mutating motility and biofilm genes, competence genes, and cannibalism genes. None of these deletions were enough to see the same levels of bacteriophage infection as the Spo0A mutant. This led the authors to theorize that multiple Spo0A-regulated pathways may be contributing to protecting B. subtilis from bacteriophage infection.

What does all of this mean?

To survive and thrive in packed environments, bacteria need to use various weapons to weaken their opponents. The authors of this paper observed a unique method that Streptomyces sp. 18-5 uses to make B. subtilis more susceptible to bacteriophage infection. They also determined that Spo0A is important for protection against bacteriophage infection but could not find any regulated genes that fully contributed to this effect. This paper answered many questions and introduced many new ones about our understanding of how microbes fight for survival in the wild.

Additional references:

- Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010 Jan;8(1):15-25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2259.

- Westhoff S, Kloosterman AM, van Hoesel SFA, van Wezel GP, Rozen DE. Competition Sensing Changes Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces. mBio. 2021 Feb 9;12(1):e02729-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02729-20.

- Valle J, Da Re S, Henry N, Fontaine T, Balestrino D, Latour-Lambert P, Ghigo JM. Broad-spectrum biofilm inhibition by a secreted bacterial polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Aug 15;103(33):12558-63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605399103.

Featured image: made by the author in BioRender