Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Faecal bacteria fighting inflammatory microbes

Alternatives to antibiotics

Not even a 100 years after the discovery of the first antibiotic penicillin, more and more microbes are becoming resistant to them. We therefore should not only use antibiotics more sparingly and caringly but we should also look for alternative solutions. One solution could be poop transplants, or, in more scientific terms, faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). The microbes present in the faeces of a healthy donor can fight harmful microbes and restore balance in the gut.

The bigger picture

The problem with the use of donor faeces to fight harmful gut microbes is that the mix of microbes in faeces is not always the same. A transplant might be efficient in some cases, but not in others, without a directly identifiable reason.

In a previous microbite I described a way to understand the bigger picture of complex microbial communities such as those in faeces in a bottom-up way: I explained how researchers put together a community from single well-known microbes, in order to better understand big microbial communities.

Another method to make sense of complex microbial mixes is to take the top-down approach: you start with the bigger picture and work your way down to the details. That is what the researchers did in this study: they started with the big microbial community of an FMT and identified the active species and their mode of action.

Faecal transplants against inflammation

The researchers specifically looked for the effect of faecal transplantation on Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP), a bacterium that is resistant to multiple antibiotics. It is often found in the intestine of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and is known to cause inflammation.

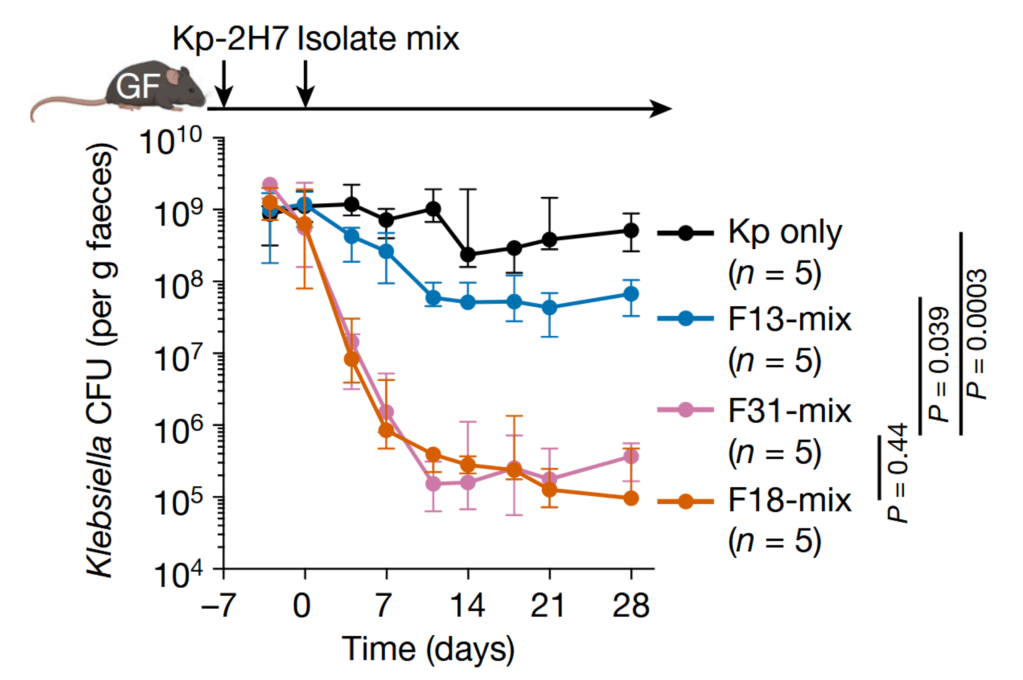

They started by adding KP to so-called gnotobiotic mice; mice that were raised in a sterile environment (without microbes) and therefore did not have a microbiome. Then, they orally administered a stool sample from one of five different human donors to the mice and looked at the amount of KP over 4 weeks. A stool sample was considered effective if it was able to decrease the amount of the harmful KP microbes in the mice.

Minimal microbe mix

Next, the researchers isolated the microbes present in the stool samples and created different mixes from the isolated microbes. The aim was to create a kind of minimal effective microbe mix from the complicated stool mixes. One of these minimal mixes, named F18 because it contained 18 out of 31 originally isolated microbes, turned out to be as effective as the original stool sample.

Competition for food

To test why the F18-mix was effective at reducing KP in the mouse intestine, the researchers looked at the gene expression of KP in the presence and absence of F18-mix. They found that genes involved in the consumption and processing of carbohydrates were less expressed by KP in the presence of F18-mix.

This suggested that KP could not eat these carbohydrates when the F18 microbes were present in the mouse intestine. F18 microbes seem to cooperate to consume food that is essential to KP, thereby reducing the harmful microbe’s numbers.

This mechanism was further confirmed when the researchers introduced mutations in KP’s genes needed for carbohydrate consumption. These mutations caused an even faster decline of KP in the presence of F18-mix, confirming that F18 and KP are competing for the same resources.

Conversely, the addition of carbohydrates (and more specifically gluconate) significantly diminished the reduction of KP in the presence of F18-mix, again implying that competition for food is involved in the way F18-mix fights KP.

Curing the microbiome

This study is a promising step towards finding alternatives to classical antibiotics. It shows that well-defined microbial communities can compete for resources with inflammatory species such as Klebsiella and potentially restore balance in sick microbiomes.

Link to the original post: Furuichi, M., Kawaguchi, T., Pust, MM. et al. Commensal consortia decolonize Enterobacteriaceae via ecological control. Nature 633, 878–886 (2024).

Featured image: https://bioart.niaid.nih.gov/