Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Of Mice and Not Just Men: Microbiome varies with both sex and gut region

If you have a TikTok account or Netflix subscription, you have likely come across the term “gut microbiome”. This refers to the diverse community of bacteria, fungi and viruses that live within our bodies, specifically those living in the gastrointestinal tract (GI).

Many studies into the microbiome have demonstrated that this community is not only diverse within our bodies, but also between different people. Many biological and lifestyle differences can contribute to microbiome differences. Some of the most prominent examples include diet, antibiotic use or immune disorders.

In recent years, studies have shown that sex and sex-linked hormones can significantly influence the composition of the microbiome. This has raised questions in the scientific community about the generalizability of findings between sexes. Additionally, many microbiome studies use samples that come from the lower part of the GI tract. Which left more unanswered questions about how the microbiome differs in the upper GI of both sexes.

For this reason, researchers decided to study how different GI locations contributed to microbiome sex differences. They collected bacterial samples from various sections of the GI tract of male and female mice at 6 and 8 weeks old and analyzed them using 16S rRNA gene sequencing (a method widely used in microbiology to identify bacteria in a sample using DNA).

At first, they found common themes between the sexes. For instance, they found significantly less bacterial diversity in the upper GI compared to the lower GI of both males and females. This diversity seemed to decrease further once mice reached 8 weeks of age. This suggests that as the mice got older and reached sexual maturity, their microbiomes stabilized.

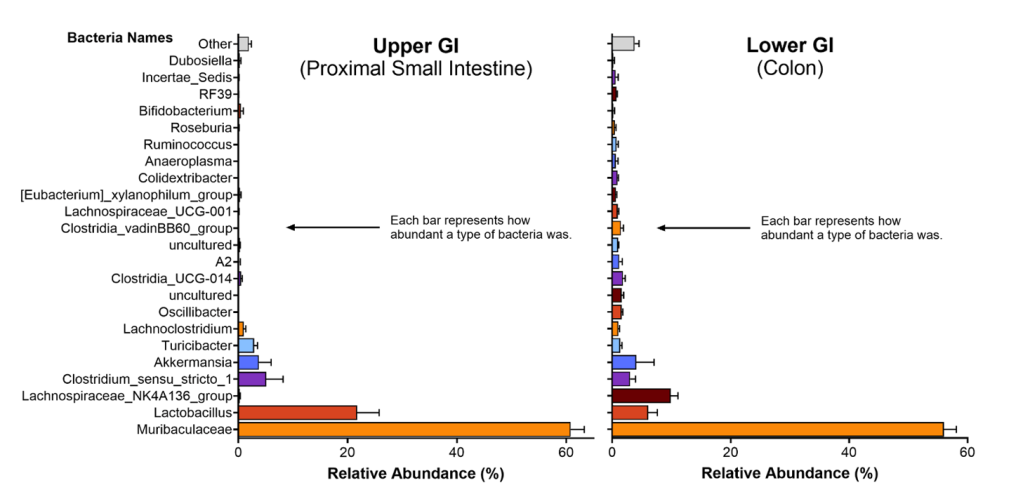

However, when they took a closer look at what bacteria were present in each group, the researchers found differences in both sex and GI location. Below, we include a relative abundance figure showing the top 18 most abundant bacteria in representative areas of both the upper and lower GI. The lower GI (colon) had much more different types of bacteria than the upper GI (proximal small intestine). Additionally, according to their statistical analysis, at 8 weeks the researchers found no significant differences in taxa abundance in both the upper and lower GI. Each region had an overall unique community. Yet, there were still interesting sex differences. For example, the bacteria Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 was more abundant in the colons of male mice, while female mice had higher levels of Dubosiella newyorkensis across all organs at 6 weeks old.

Many studies over the years have proposed that sex-related hormones may be one of the main reasons behind microbiome sex differences. Because of this, the researchers measured the levels of progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone in the blood of the mice. Their analysis showed correlations between specific bacteria and hormone levels. For example, higher estradiol levels were associated with an increase in certain bacteria like Adlercreutzia mucosicola and Parvibacter, which are known to interact with estrogen and were found to be higher in females.

Like in all aspects of life, representation matters. Historically, many clinical studies have been conducted exclusively on healthy, white males. Even studies that included both sexes often don’t include this information in the actual analysis. For example, a pollution study conducted in Canada only detected health impacts once they sorted their data by sex. Had they pooled the results, they would not have concluded the same. These biases have led to a lack of accurate representation of the rest of the world concerning (medical) treatment development. The microbiome world is not exempt from this bias either. This study underscores the complexity and importance of considering these factors in experimental research and clinical interventions to ensure accurate results, to better understand the microbiome’s role in health and disease, and to develop more effective treatments.

Overall, the study highlights the dynamic nature of the gut microbiome and its responsiveness to various factors such as sex, age, and localization within the gut. These results emphasize the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the microbiome and how it changes within each of us.

Link to the original post: Ortiz-Alvarez de la Campa, Melanie; Curtis-Joseph,N.; Beekman, C.; Belenky, P. 22 January 2024. Gut Biogeography Accentuates Sex-Related Differences in the Murine Microbiome. Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms, Providence, RI, USA. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12010221. 28 May 2024.

Featured image: by author on Procreate

Additional sources:

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; 2024; Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials; https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials.html; Accessed: 30 May 2024

Hwashin Hyun Shin, Rajendra Prasad Parajuli, Aubrey Maquiling, Marc Smith-Doiron; 1 July 2020; Temporal trends in associations between ozone and circulatory mortality in age and sex in Canada during 1984–2012; Volume 724; Science of The Total Environment;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137944