Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

To Fight or Not? Sensing the Answer

Your skin is not only yours, but also the home to millions of micro-organisms. Yet the immune system in your body doesn’t blast out weapons to kill them. How does that work? There are many ways and today we will discuss one such mechanism.

Immune cells are powerful weapons that can unleash damage but have to be controlled to minimize unnecessary bloodshed. One way of doing this is ensuring that immune cells can only unleash weapons when the enemy is present, so adaptive immune cells are generally specific for one particular enemy. In a recent study, researchers introduced bacteria (previously not present in or on the mice) onto the skin of mice. They saw the accumulation of immune cells specific to these bacteria in the skin without any sign of inflammation. The bacterial enemy is present, and the immune cells are ready, yet there is no war. How’s that happening? That’s exactly what the authors investigated as well.

They saw that these immune cells – specifically CD8 immune cells (a type of adaptive immune cells) – were present close to sensory nerves in the skin. You can tell how prepared the immune cells are for war by looking at their shape. The rounder their shape, the more activated, which means they are likely to attack. Interestingly, the immune cells closer to the sensory nerves were less activated (less ‘round’), as though amidst war preparation, they were informed about ongoing peace negotiations. The authors wondered: who are these messengers?

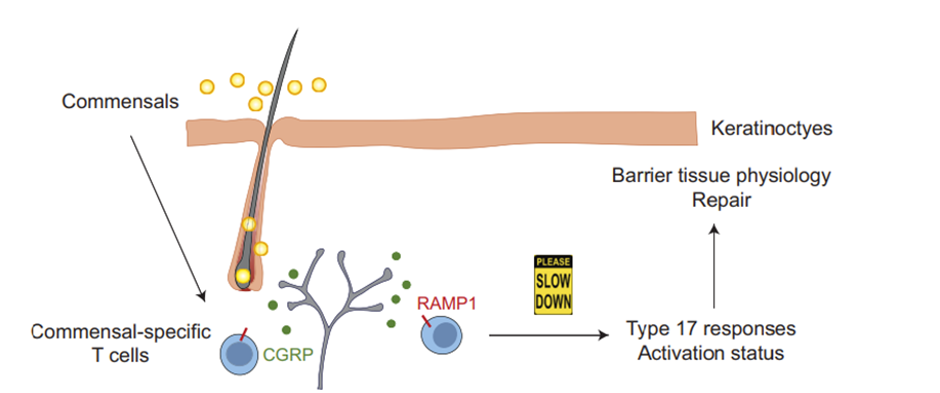

Sensory neurons can secrete certain chemical molecules called neuropeptides, and other cells in the body, including immune cells, can have receptors for them. The authors noticed that upon skin colonisation by bacteria, a certain class of immune cells specific to the bacteria expressed a receptor for a neuropeptide. This did not happen when the bacteria were present inside the body, beyond the skin.

Our body is so clever, there is a separation based on skin: When the bacteria are present inside the body, they pose a danger to us, eating resources that could be important to our cells whereas while they are on our skin, they’re not causing any problem. It would be better to leave them undisturbed, rather than spending energy waging war against them.

The neuropeptide is released by the neurons in response to the bacteria. When the neuropeptide is present, these immune cells are signalled to silence their war response – such as the secretion of certain chemical molecules called cytokines. These cytokines would interact with other cell types such as keratinocytes in the skin and prepare them for war as well. In addition, they would prepare for any sort of post-war recovery such as wound healing. In the absence of this interaction, there are more immune cells recruited to the skin and these cells are now ready to wage war unnecessarily.

This paper describes an elegant mechanism for how peace is maintained on our skin through neuroimmune crosstalk. The signalling between the neurons and immune cells is seen as a variable resistor of immune cell activity, controlling when immune cells need to wage war and when they can win negotiations simply by a show of force and regular patrolling.

Thinking about this study in terms of medical potential is exciting. It may be possible to utilize the neuropeptide artificially to signal the immune cells to not wage war in unnecessary conditions such as when the body is not able to control its immune system, as is the case in autoimmune skin diseases

Link to the original post: Kulalert W, Wells AC, Link VM, Lim AI, Bouladoux N, Nagai M, Harrison OJ, Kamenyeva O, Kabat J, Enamorado M, Chiu IM, Belkaid Y. The neuroimmune CGRP-RAMP1 axis tunes cutaneous adaptive immunity to the microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Mar 12;121(11):e2322574121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2322574121

Featured image: Source (NIAD) [“Immune Cells Surrounding Hair Follicles in Mouse Skin” by NIAID is licensed under CC BY 2.0.]