Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

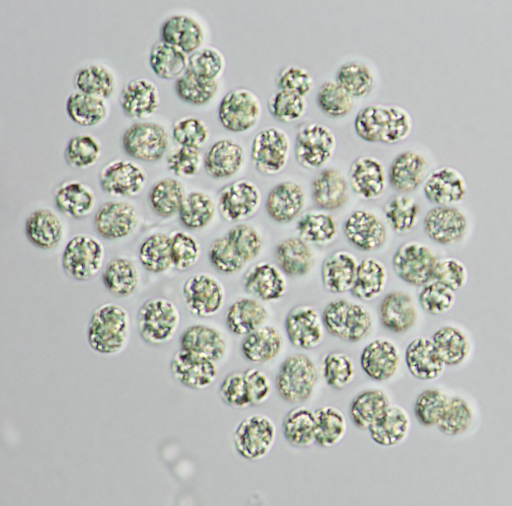

Slime after slime: “Algae” plagues a Florida lake

What’s in a name? In biology, it’s not always simple. Electric eel: electric, yes; eel, no. Guinea pig: neither Guinean nor a pig. King cobra: not a cobra and definitely not a king – monarchy is an exclusively human invention. And then there’s blue-green algae, which are not algae at all. This is the common name for many different species of cyanobacteria. They are a type of bacteria that use photosynthesis, like plants. Chlorophyll, along with other pigments, give it its distinctive colour. At least the “blue-green” part is correct.

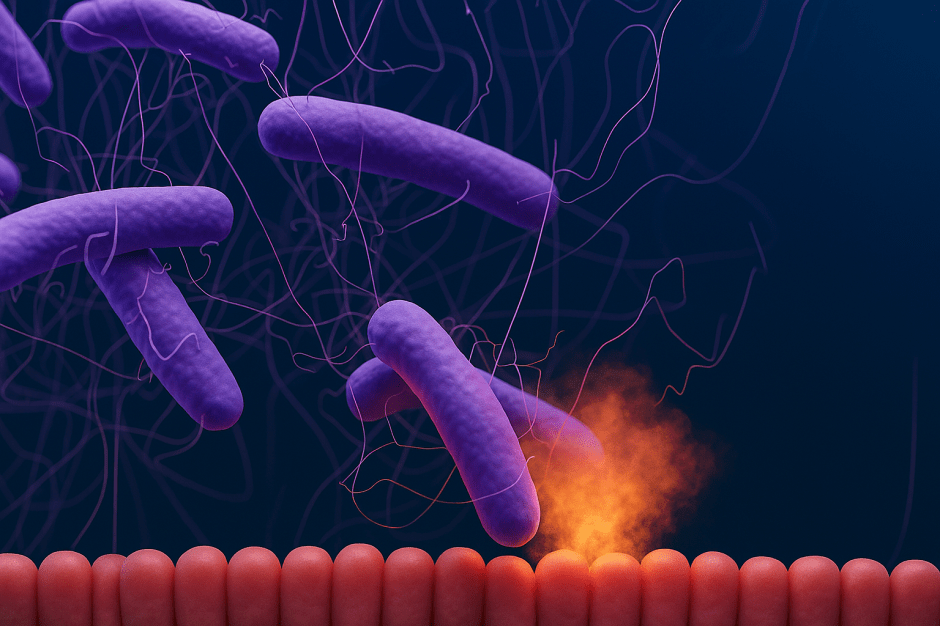

Blue-green algae usually live in colonies on the surface of water. When these colonies grow out of control, they’re known as harmful algal blooms (HABs). When they grow large enough, they can even be seen from space! HABs often produce toxins that harm not only the aquatic ecosystem they inhabit, but surrounding terrestrial life – including us. But how does it happen?

Too much of a good thing

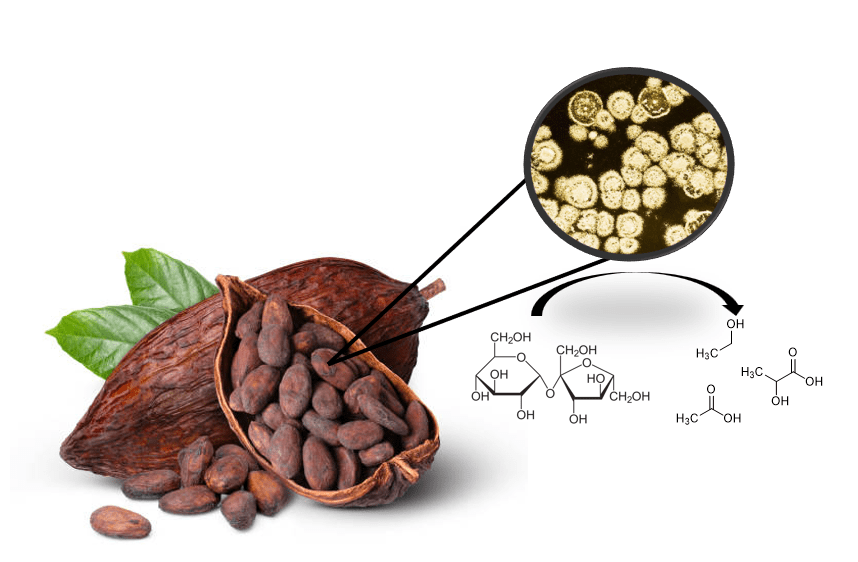

HABs are a result of a process known as eutrophication. It works like this: An excess of nutrients enters the water, usually nitrates and phosphates. This comes from human activity, with fertiliser runoff from commercial agriculture being the main culprit. It might be waste to us, but the blue-green algae thrive on it.

Algae reproduce quickly, with the colonies forming layers that cover the surface of the water. This is called an algal bloom. The algae block the sunlight from reaching plants that grow below the surface of the water, and they die. This changes the environment so much that the algae also die. Bacteria in the water feed off the dead plants and algae, using up any remaining oxygen and giving off carbon dioxide. This low-oxygen environment causes the death of most remaining plants and animals (if they can’t swim away).

A closer look

In the summer of 2018, a large HAB grew on Lake Okeechobee in Florida. The HAB was caused by the growth of Microcystis aeruginosa, a type of blue-green algae that produces toxins called microcystins. Researchers were interested in studying possible health effects of HAB exposure.

Local residents were recruited to complete written questionnaires asking for details about their health history, exposure to local waterways, and any symptoms of toxin exposure they had experienced during the summer, including respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms and skin rashes.

Because it’s difficult to attribute specific symptoms to HAB exposure, researchers were most interested in the number of overall symptoms reported by each participant. Exposure was classified into one of three categories: residential exposure (living on a waterway), recreational exposure (swimming, boating, fishing, etc.) and occupational exposure (marina workers, water quality technicians, etc.).

Something in the air

Participants who reported residential exposure reported a significantly higher average number of symptoms, compared to those who did not. There was no significant association between occupational exposure or recreational exposure, and number of symptoms experienced.

This suggests that people who live in close proximity to an affected waterway have the highest risk of health problems caused by HABs. Recreational and occupational exposure seem to suggest much closer contact with algae, so how could this be?

One explanation is that the main route of exposure is via inhalation. Microcystin particles are very small and light, easily becoming aerosolised. People living on waterways spend more time breathing in the affected air, in comparison to the 2 other groups.

Another possible explanation is that participants in the recreational and occupational groups are more aware of the dangers of HABs. Though they are in closer proximity to the HAB, they take steps to mitigate the risk, such as wearing protective clothing.

As for symptom types, the study provided evidence for an association between both respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, and HAB exposure. Interestingly, there was little evidence of an association with skin complaints.

Participants with a history of asthma reported, on average, twice the number of symptoms compared to those without asthma. This seems to support the theory that inhalation is the main method of microcystin exposure.

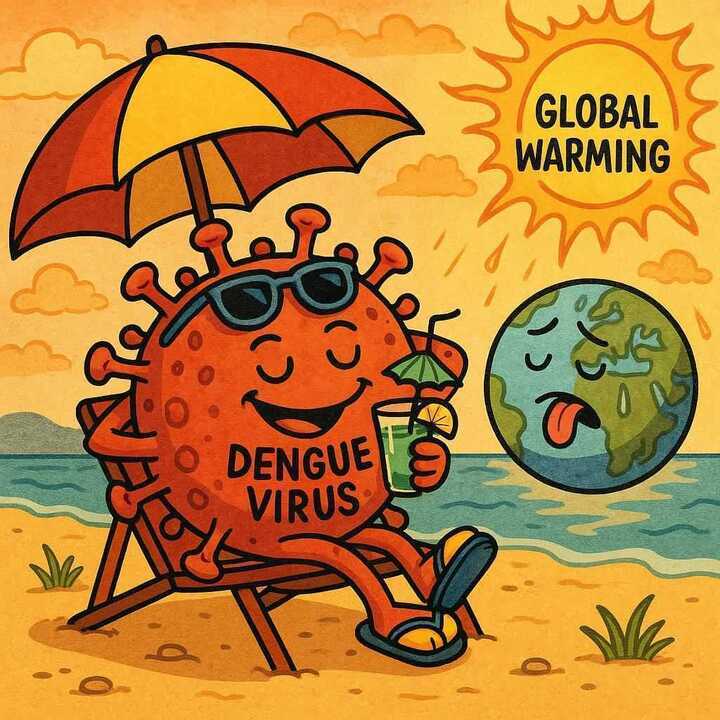

The waves of the future

If you haven’t heard much about HABs, that will probably change. This study was undertaken in 2018 and published in 2023, but the Lake Okeechobee HAB is now a predictable yearly event. It was even featured in the New York Times last summer.

HABs are a growing problem everywhere in the world, not just in North America. In Europe, the estimated cost of HABs to industries including fishing and tourism is estimated to be over € 918 million. It’s not just pollution driving the increase in HABs – the warming effect of climate change contributes too.

It’s well-established that HABs have a negative effect on human health. And with a tremendous environmental and financial cost, harmful algal blooms are really living up to the name.

Link to the original post: Reif JS, Stockley N, Harvey K, McFarland M, Gordon SC, Schaefer AM. Symptom frequency and exposure to a cyanobacteria bloom in Florida. Harmful Algae. 2023 Nov;129:102526. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2023.102526. Epub 2023 Oct 17. PMID: 37951612.

Featured image: Microcystis aeruginosa Microscopic View. Image source: U.S. Geological Survey/photo by California Water Science Center, 2015