Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

High-Dose Probiotics Improve Mood in Stress Model

Every year, millions of people suffer from anxiety and depression, but current medications don’t work on them. For this reason, scientists are searching for new avenues of mental health treatment. A new study from researchers in Ghana brings us one step closer to understanding how the bacteria in our guts might help us provide relief for those millions.

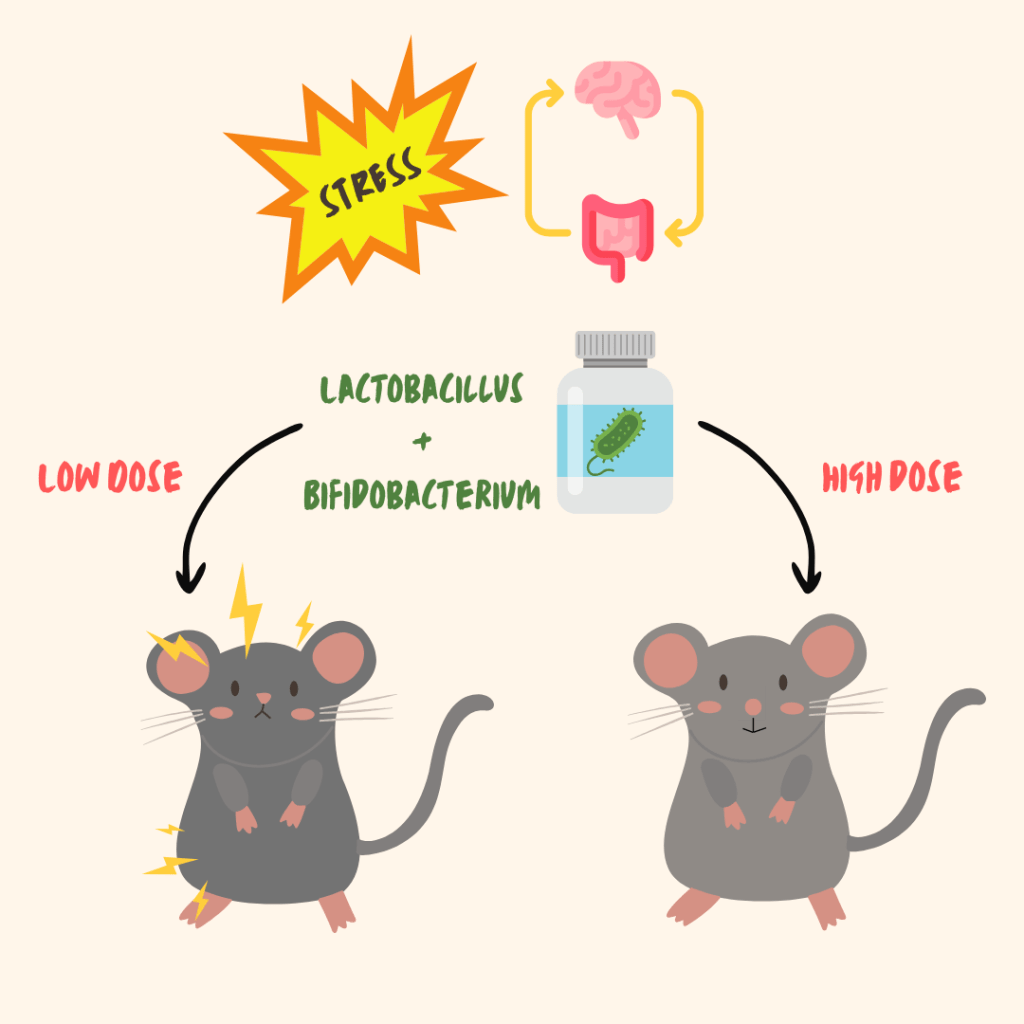

The researchers focused on two common types of probiotics (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) and tested their ability to reduce depression and anxiety-like behaviors in mice exposed to chronic stress. What they found was promising: when given in high doses and especially when combined, these probiotics helped reverse many of the negative effects of stress. In some ways, they worked similarly to the antidepressant fluoxetine.

The study used a well-known mouse model called chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS), which mimics the effects of ongoing, everyday stress. This kind of stress doesn’t just wear on the brain, it also weakens the gut barrier, activates the immune system, and alters the microbiome. That’s why the gut-brain axis, the communication highway between the gut and the brain, has become a popular target in mental health research. In this case, the authors wanted to know whether probiotic strains could ease depression-like symptoms through this pathway.

To explore this, the team divided sixty-three mice into nine groups. Some mice were kept as healthy controls, while others were exposed to stress. The stressed groups were given either low or high doses of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, a combination of the two, or fluoxetine. After two weeks of stress and four weeks of treatment, the researchers assessed behavior using multiple tests for depression, anxiety, and even pain sensitivity.

The results showed that probiotic treatment had a clear, dose-dependent effect on the mice’s stress levels. Mice that received high doses of either a single strain or the combined probiotic therapy showed improved behavior across the board. They gained weight back after losing it during stress. They showed renewed interest in sugary water, which is a sign that their anhedonia (the loss of pleasure or interest) had improved. They were more active and mobile in the forced swim and tail suspension tests, suggesting less behavioral despair (a depression symptom). In the open field test, they explored more and spent less time clinging to the edges, which is an indicator of reduced anxiety.

Interestingly, low-doses of a single bacteria didn’t have the same effect. Combining Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium seemed to enhance the impact even at lower doses, which could be especially helpful for people who can’t tolerate high doses of a single strain. In fact, some effects, like increased “curling” behavior in the tail suspension test, were only observed with probiotics, not with fluoxetine. This suggests that while both treatments helped, they may work through different biological pathways.

Importantly, the probiotics did not cause hyperactivity or act as psychostimulants. Their antidepressant-like effects were not due to increased energy or motor function, but rather to specific improvements in stress-related behaviors. This was confirmed through the open field test, where mice explored more of the testing area without a spike in overall movement.

In the end, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that the gut microbiome can influence brain health. It also highlights that not all probiotics are created equal; dose and strain combinations matter. For people looking for new tools to support mental health, especially those interested in natural or gut-focused interventions, these findings offer real promise. With more research, especially in humans, probiotics could become part of a holistic approach to treating stress-related mood disorders.

Additional sources

- Penn E, Tracy DK. The drugs don’t work? antidepressants and the current and future pharmacological management of depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2012 Oct;2(5):179-88. doi: 10.1177/2045125312445469. PMID: 23983973; PMCID: PMC3736946.

- Williams, N. T. (2010). Probiotics. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 67(6), 449-458. https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article/67/6/449/5130018

- Zhang, Z., Lv, J., Pan, L., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Roles and applications of probiotic Lactobacillus strains. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 102, 8135-8143. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-018-9217-9

- Chen, J., Chen, X., & Ho, C. L. (2021). Recent development of probiotic bifidobacteria for treating human diseases. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 9, 770248. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/bioengineering-and-biotechnology/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2021.770248/full

- Gram, L. F. (1994). Fluoxetine. New England Journal of Medicine, 331(20), 1354-1361. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm199411173312008

- Sharma, S., Chawla, S., Kumar, P., Ahmad, R., & Verma, P. K. (2024). The chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) Paradigm: Bridging the gap in depression research from bench to bedside. Brain research, 149123. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006899324003779

- Wei, L., Li, Y., Tang, W., Sun, Q., Chen, L., Wang, X., … & Ma, X. (2019). Chronic unpredictable mild stress in rats induces colonic inflammation. Frontiers in physiology, 10, 1228. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01228/full

- Lv, W. J., Wu, X. L., Chen, W. Q., Li, Y. F., Zhang, G. F., Chao, L. M., … & Guo, S. N. (2019). The gut microbiome modulates the changes in liver metabolism and in inflammatory processes in the brain of chronic unpredictable mild stress rats. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2019(1), 7902874. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1155/2019/7902874

- Mayer, E. A., Nance, K., & Chen, S. (2022). The gut–brain axis. Annual review of medicine, 73(1), 439-453. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-med-042320-014032

- Rizvi, S. J., Pizzagalli, D. A., Sproule, B. A., & Kennedy, S. H. (2016). Assessing anhedonia in depression: Potentials and pitfalls. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 65, 21-35. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763416301282

- Berrocoso, E., Ikeda, K., Sora, I., Uhl, G. R., Sánchez-Blázquez, P., & Mico, J. A. (2013). Active behaviours produced by antidepressants and opioids in the mouse tail suspension test. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 16(1), 151-162. https://academic.oup.com/ijnp/article/16/1/151/628719

- Koob, G. F., Arends, M. A., McCracken, M. L., & Le Moal, M. (2020). Psychostimulants (Vol. 2). Academic Press.

Featured image: Created by the author using Canva Pro.