Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

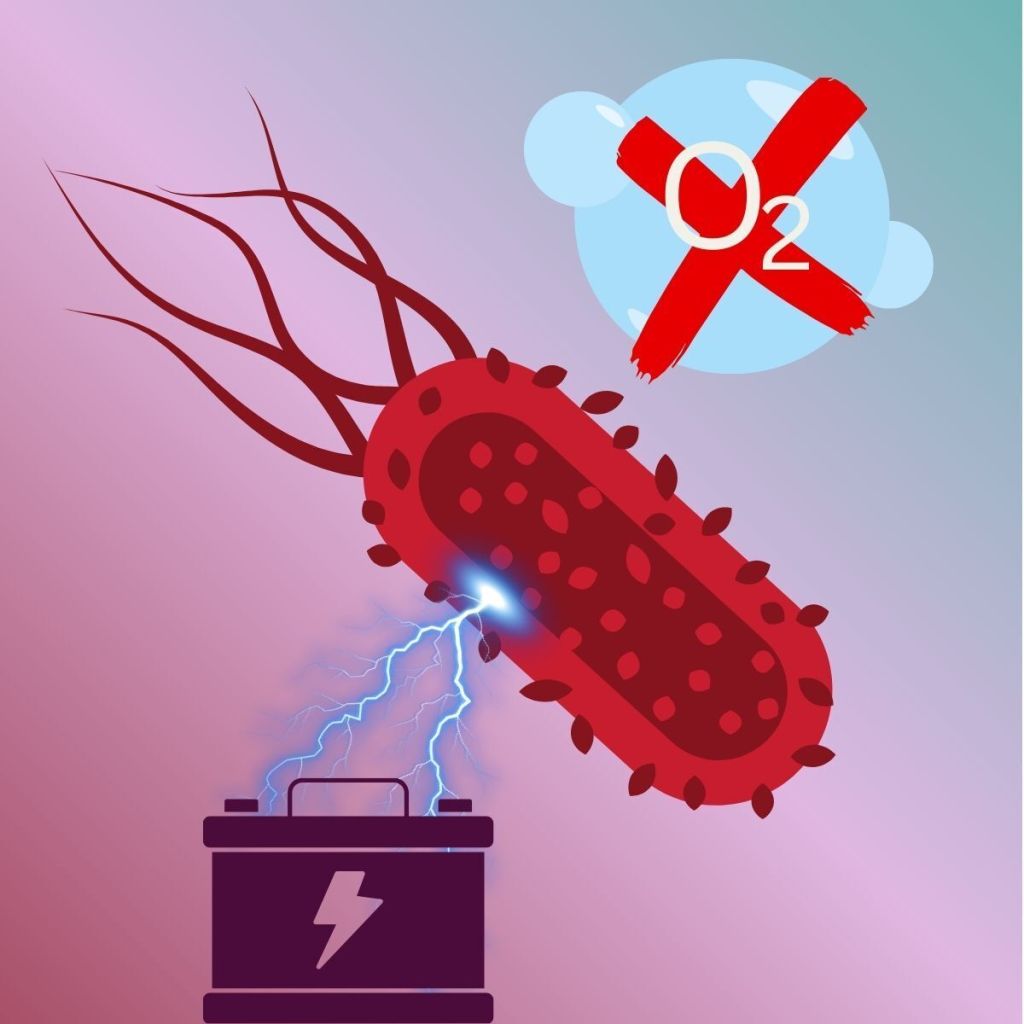

Beyond oxygen: an electric way to thrive

Eating and breathing are two processes for a singular purpose: energy. When you breathe, the complex carbon molecules you eat are oxidized and broken down inside your cells to the simplest components. This happens through redox reactions, where some molecules are oxidized (lose electrons) and others are reduced (gain electrons). The energy released by this process fuels your every movement, action, and thought.

When we discuss cell respiration, we refer to the process by which an organism obtains energy through the chemical oxidation of molecules. This process is complex, involving many proteins and parts of the cell. And even the humble Escherichia coli (E. coli) will oxidize carbon molecules (like glucose, a sugar) and reduce oxygen. But when oxygen is unavailable, most cells (including yours) can respire through fermentation. That is a less efficient process, but it follows the same principle: oxidize carbon molecules and reduce other molecules, resulting in energy.

When oxygen is present in respiration, it is reduced and expelled as H2O. During fermentation, organic molecules are reduced and also expelled. But what if cells could reduce something else when oxygen was not available?

Bacteria have managed to live in the most barren places, deep in the earth and soil. No light. No oxygen. No other organisms around. How? Something called extracellular respiration. The process relies on reducing components outside the cell, usually metals. This is done by components on the membrane, or by internalizing the metals into the cell, or by something called “electron shuttles”. These are molecules that are reduced inside the cell, gaining electrons, which then diffuse to the environment, pass the electrons to another source, and are picked back up by the cells in their original, oxidized state again.

A team of researchers has done in-depth experimental analysis on E. coli, demonstrating that we have overlooked a complex respiratory method… in the most studied microbe!

The work done by the scientists involved sequentially mutating many proteins of E. coli, and then studying how the bacteria grew. At first, they discovered that a protein called 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (HNQ) serves as an electron shuttle. The bacteria can shuttle HNQ in and out, first taking electrons to outside molecules, reducing them, and then recuperating the oxidized HNQ molecule. This happened with a normal metabolism.

What about when oxygen is not present, in anaerobic conditions? The researchers wanted to answer this question. They placed the bacteria with food, an external anode (to be reduced by external respiration), and saw that the bacteria still used HNQ to shuttle electrons to the anode. They could even measure how much the anode was reduced.

To find the proteins responsible for reducing HNQ, they mutated multiple enzymes. They found that two enzymes, nitroreductases NfsB and NfsA, were mainly responsible for reducing HNQ, but other enzymes contributed as well. Nitroreductases are enzymes that reduce nitrogen atoms, which HNQ has.

But bacteria were still reducing fermentation byproducts as normal during anaerobic respiration. HNQ electron shuttling and external respiration happened in parallel to the normal anaerobic respiration. There was one fundamental question left to answer. Was extracellular respiration a crutch or an actual system capable of sustaining the bacteria by itself? To answer this, the scientists inactivated all the genes responsible for making proteins that reduced fermentation byproducts. This meant that, under anaerobic conditions, the bacteria had only two options. Survive using only extracellular respiration, or die.

Imagine their surprise when the bacteria not only survived, but thrived! The bacteria showed they could shuttle more and more electrons over time, and kept growing. And something unexpected happened, too. After a while, the speed at which they shuttled electrons increased dramatically. The researchers thought something was off, and sequenced the bacteria. They expected major changes in their protein expression, but found only a single, small mutation on a membrane transport protein.

In the end, it turns out E. coli is capable of thriving using extracellular respiration, as long as it can reduce a material in its surroundings. Although originally sub-optimal, small mutations made the bacteria much better at growing using only extracellular respiration. All this has several important implications. First of all, we were unaware that the most studied bacteria ever was perfectly capable of surviving this way. What other bacteria could be doing this? Second of all, it turns out molecules like HNQ are not that rare. In fact, in the wild, some bacteria take similar molecules made by other organisms, like plants, and use them to perform extracellular respiration. E. coli lives in the guts of humans and animals, and perhaps nearby bacteria use E. coli’s HNQ to do a similar process, even if they cannot synthesize HNQ. That might have larger ramifications than we expected. For example, reduced metals in our guts are absorbed better. What if E. coli and other bacteria performing extracellular respiration in our guts helps us to absorb iron, copper, or manganese from our meals? It is clear there is much we do not know, and we need to do more research to fully understand how bacteria in our bodies and the environment live. The scientists did not only provide a base for more research, but also a comprehensible protocol to test the extracellular respiration of other bacteria. Because of this, exciting discoveries might follow the results showcased here.

Link to the original post: Extracellular respiration is a latent energy metabolism in Escherichia coliKundu, Biki Bapi et al.Cell, Volume 188, Issue 11, 2907 – 2924.e23

Additional sources: Extracellular respiration. Jeffrey A Gralnick, Dianne K Newman. Mol Microbiol. 2007 Jul;65(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05778.x

Featured image: designed by the author (Darío Sánchez Martín) on Canva