Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbial molecular warfare: When prey becomes predator

Microorganisms have a vast molecular toolkit to interact with each other. Bacteria share plasmids, shielding their neighbors against antibiotics. Viruses infect bacteria, fungi, and all kinds of organisms, using their victims’ molecular machinery for their own gain, often killing the cells in the process. And larger microorganisms, like amoebas or nematodes, often feed on small microorganisms, such as bacteria.

And while it might sound simple, it is anything but. Bacteria have honed the art of chemotaxis. In the microscopic world, each cell leaves molecules lying around, like breadcrumbs in the forest. They move by picking up other signals and taking the most seemingly convenient direction based on those signals. That is chemotaxis. A complex decision-making system interprets these chemical and molecular signals.

Amoebas, a natural predator of bacteria

Amoebas are unicellular eukaryotes, and they can form colonies as well. Most amoebas feed on bacteria, and because of that, they are known as bacterivorous. They chase bacteria using chemotaxis, following the molecules the bacteria have left around until they find their prey. Then, they engulf and digest them. But there is another twist. Bacteria can make molecular weapons, releasing them into the environment, to kill their predators.

Bacteria deploy molecular weapons against amoebas

Researchers knew this indeed happened with bacteria and amoebas. Some species of bacteria are immune to amoebas eating them. To know how this happens, the researchers took a common species of bacteria, Pseudomonas syringae. They tested how several strains of the bacteria did against amoebas. While most strains were defenseless, they identified one that wasn’t, SZ47. This strain had no problem growing when amoebas were around.

The researchers compared SZ47 with a genetically similar strain, SZ57. This strain, however, was eaten by the amoebas. So, the researchers wanted to see if SZ47 produced some molecules that SZ57 didn’t. At first, they found nothing relevant. Then, they grew the bacteria with amoebas nearby. That is when they found differences. In the SZ57 cultured with amoebas, they found two specific molecules, called octapeptides. And on the culture of SZ47 with amoebas, they found a different set of two molecules, pyrofactins. Octapeptides did not affect amoebas, but pyrofactins were lethal to them.

A chemical radar lets SZ47 produce pyrofactins to kill amoebas

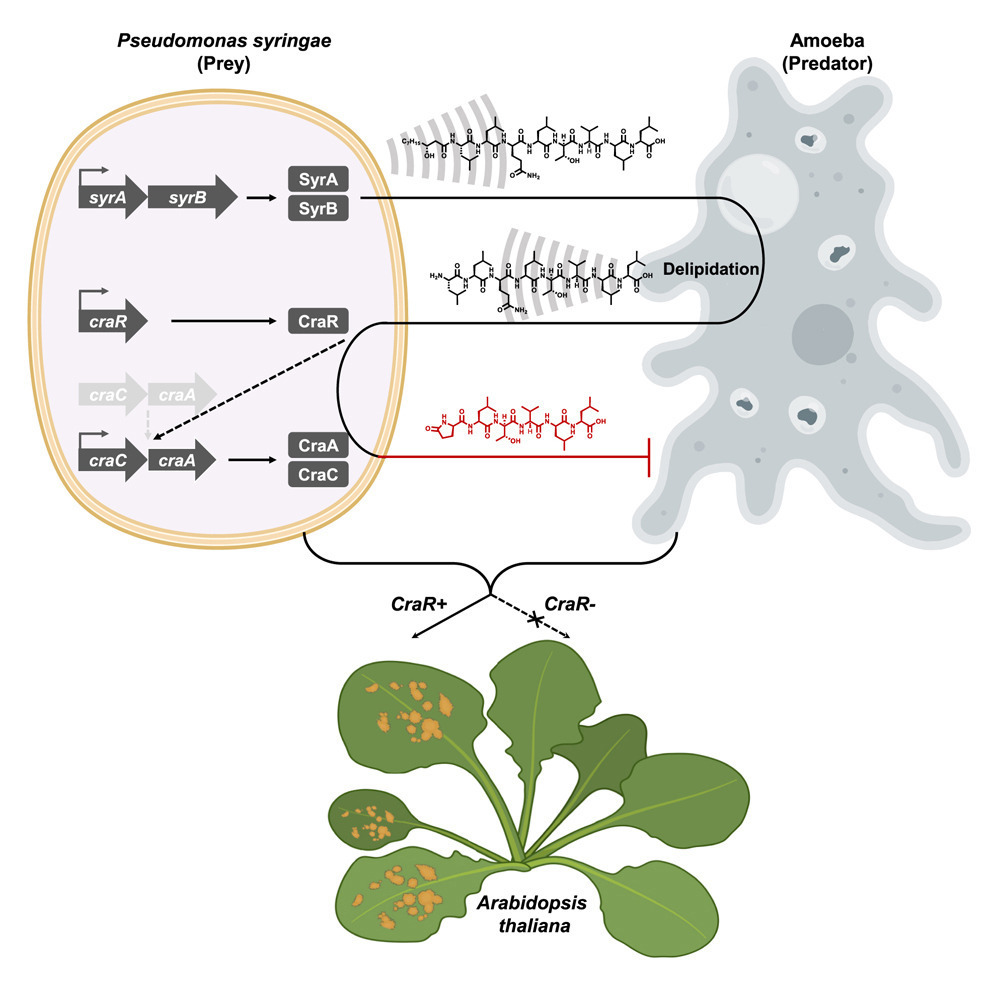

So how does this happen? It is a fascinating example of chemosensing. Both strains, SZ47 and SZ57, produce and secrete a molecule called syringafactin. Amoebas pick up the syringafactin and transform it into octapeptides.

For SZ57, that was that. But for SZ47, it does not end there. That strain recognizes the octapeptides with a membrane protein, CraR. This protein then activates genes that allow the bacteria to transform the octapeptides into pyrofactins. The bacteria secrete the pyrofactins into the environment, which kill the amoebas.

Image Source: Graphical abstract from the paper (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.02.033)

SZ57 has the same genes and can produce pyrofactins. But the researchers found that it lacks the CraR protein. This means SZ57 cannot recognize the octapeptides from the amoebas. Because of that, the genes to make pyrofactins are never expressed in SZ57. When the scientists gave SZ57 the CraR protein, the bacteria fought the amoebas and lived, just like SZ47. And it seems that CraR helps the bacteria grow on plant leaves when the amoebas are around.

Lastly, the researchers investigated the specifics of the chemosensing and molecular warfare that the amoebas and SZ47 wage on each other. It turns out that bacteria secrete the syringafactin, which diffuses quickly around them. The amoebas modify it, and the final product diffuses fast, back towards the bacteria. That is when the bacteria make the pyrofactin. When the amoebas come into contact with pyrofactin, they die, like hitting a chemical mine.

Just a piece of the puzzle

This is only a small snapshot of the chemotaxis and chemosensing microorganisms do and the molecular warfare that can turn an unsuspecting predator into prey. The scientists themselves acknowledged that we know very little about everything that happens at the microscopic level. Can SZ47 use CraR and the syringafactin system to sense other predators? Or are there other molecular mechanisms in play for the many bacterivorous organisms, such as nematodes, different amoebal species, and other protozoa?

We do not know as of yet, but it is clear that there are complex and nuanced interactions happening all around us. And today, we are one step closer to understanding them.

Featured image: Image created by the author (Darío Sánchez Martín), under CC-BY 4.0