Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Fighting Side by Side with a Bacteria

While most microorganisms are commonly seen as the enemy for causing disease, some microorganisms, found in the microbiota, are helpful allies in the fight against pathogens. The microbiota refers to the vast number of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, that naturally colonize various regions of the human body, such as the skin, the gut, the upper respiratory tract (nasal cavities, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx), and the lower respiratory tract (trachea and lungs).1 These microbiota communities are known to typically have a mutually beneficial relationship with the host, often helping to maintain human health rather than harm it.2

Research has recently shown that the upper and lower respiratory microbiota appear to influence the possibility or severity of respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia, pulmonary tuberculosis, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and influenza.1, 2, 3, 4 These studies have found that dysbiosis (disruption leading to an imbalance) of the microbiota often leads to worse infections and is linked to increased decline of lung function, suggesting that these microbiota communities play a defensive role during infection.

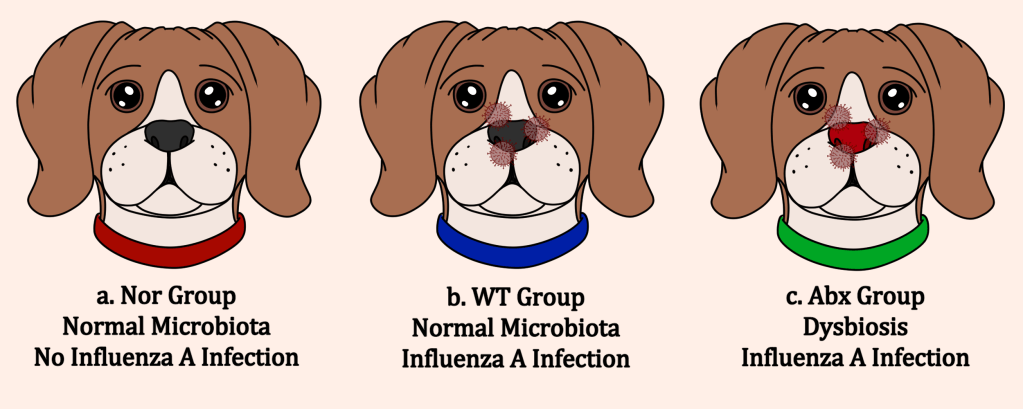

In this study, Geng and their team sought to show a direct link between the upper and lower respiratory tract microbiota and susceptibility to influenza viruses, as well as begin an understanding of the underlying mechanisms behind this association. To do so, they established three groups of dog models: the Nor group, which received no antibiotic treatment to disrupt the nasal microbiota (no dysbiosis) and was not exposed to influenza A, the wild type (WT) group, which received no antibiotic treatment as well but was exposed to influenza A, and the Abx group, which received antibiotic treatment (causing dysbiosis) and was exposed to influenza A (Figure below).

The researchers found that in the Abx group, genes associated with interferon production showed a significant decrease in expression. Interferons are cell signals critical for host defence against viruses, usually responsible for initiating immune responses at the early stages of infection.5 This suggests that the dysbiosis could reduce the host’s antiviral immune response.

They also found that in the Abx group, mucin-associated genes and inflammatory cytokine genes had significantly increased expression. While mucus is a protective barrier in the respiratory system against invaders, overproduction can lead to complications in respiratory diseases, like increased susceptibility to infections, decreased lung function, and increased mortality. Inflammatory cytokines are released as a signal to activate the immune system, but overexpression of these genes can cause tissue damage, which was seen in lung tissue samples.6 This suggests that the microbiota might have a role in regulation of these immune signals, which is lost during dysbiosis.

While comparing the microbiota communities, the researchers noticed that the Abx group had a decreased amount of Lactobacillus bacteria present but an increased number of Moraxella bacteria present compared to the Nor and WT groups in both the nasal cavities and the lungs. The researchers then looked to see what impact Lactobacillus bacteria might have on gene expression during influenza infection in human cells.

During influenza infection, the presence of Lactobacillus significantly decreased the amount of virus and significantly increased the host cell’s expression of interferons and autophagy-related genes. Autophagy is a process the cell can naturally use to deliver viral invaders to the lysosome for degradation, but this process is often blocked by influenza A. From these results, it appears that Lactobacillus bacteria may be capable of interfering with this virus-induced autophagy block and allow for destruction of the virus.

The researchers concluded that disruption of the nasal microbiota led to an amplified influenza infection by causing variations in pathways linked to the microbiota. This dysbiosis results in an excessive secretion of mucus, leading to uncontrolled inflammation and abnormal airway function. The dysbiosis might also reduce the host’s interferon-mediated antiviral immune response and lead to increased tissue damage, seen in the reduction of interferon-stimulated gene expression levels and increased inflammatory cytokines in the Abx group.

The authors suggest that the key regulator in this host-microbiota interaction is Lactobacillus, which was decreased in the Abx group. Lactobacillus was shown to lead to increased interferon expression in host cells and to be capable of reactivating the host cell’s autophagy pathway, overcoming blockage from influenza A. However, more research needs to be done to understand the mechanism behind Lactobacillus’s communication with the host cell and antiviral response.

The microbiota is made of a large and varied community of microorganisms that is still not understood or characterized well. While continued studies need to be done to understand how exactly the microbiota supports human health, it is evident that these unexpected allies are critical in protecting their hosts from pathogens and supporting immune response during infection.

Link to the original post: Geng J, Dong Y, Huang H, et al. Role of nasal microbiota in regulating host anti-influenza immunity in dogs. Microbiome. 2025 Jan 27;13(27). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-025-02031-y

Featured image: Created by the author with Clip Studio Paint

Additional sources:

Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 28;20(23):6008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20236008

Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Apr 23;7(135). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00974-4

Shah T, Shah Z, Baloch Z, Cui XM. The role of microbiota in respiratory health and diseases, particularly in tuberculosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Nov;143:112108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112108

Rosas-Salazar C, Kimura KS, Shilts MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and viral load are associated with the upper respiratory tract microbiome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Apr;147(4):P1226-1233.E2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.001

Tsang TK, Lee KH, Foxman B, et al. Association between the respiratory microbiome and susceptibility to influenza virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Sep 28;71(5):1195-1203. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz968

McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015 Feb;15:87-103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3787