Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

The phage pirates of Lake Mendota

Viruses have pretty simple “lives.” Pretty much their only goal is to create progeny. They don’t eat, they can’t move, and they can’t even reproduce without hijacking a host. Bacterial viruses, called phages, have a special ability to live vicariously through their hosts. They do this by robbing important metabolic genes from their hosts and then forcing the hosts to express these genes during infection to ensure more successful infection outcomes for themselves.

A new study takes an unprecedented look at phage evolution over a twenty-year period with a focus on these stolen host auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs). The study, which uses a Minnesota lake as a natural laboratory, aims to understand how viruses and infection dynamics evolve over an extended period of time. What they discovered will cause scientists to rethink existing paradigms in viral ecology and evolution.

In order to identify the viruses and their bacterial hosts, the researchers sequenced the DNA in the water samples collected from the lake across 6 different seasons for two decades. Then, using a very computationally intensive process, they reassembled this DNA into bacterial and viral genomes. They were able to match viruses to prospective hosts by leveraging similarities between viral and host genomes that arise from the evolutionary warfare in which they are engaged.

Using this strategy, the scientists identified an astounding amount of new diversity of viruses in the lake water. They recovered 1,307,400 viral genomes, constituting about a quarter of the entries in the IMG/VR v4 database — one of the largest existing databases of uncultured viral sequences.

With this rich new dataset of viruses, the authors investigated how viruses use AMGs originally stolen from their hosts. AMGs with all kinds of functions have been discovered in viruses across environments, and microbial ecologists commonly think of them as playing an integral role in infection dynamics. Accordingly, this study focused on the AMGs of phages infecting three ecologically important host groups: Cyanobacteria (photosynthetic bacteria), methanotrophs (bacteria who get their energy from methane), and Nanopelagicales (a genus of ultrasmall bacteria prevalent in lakes worldwide).

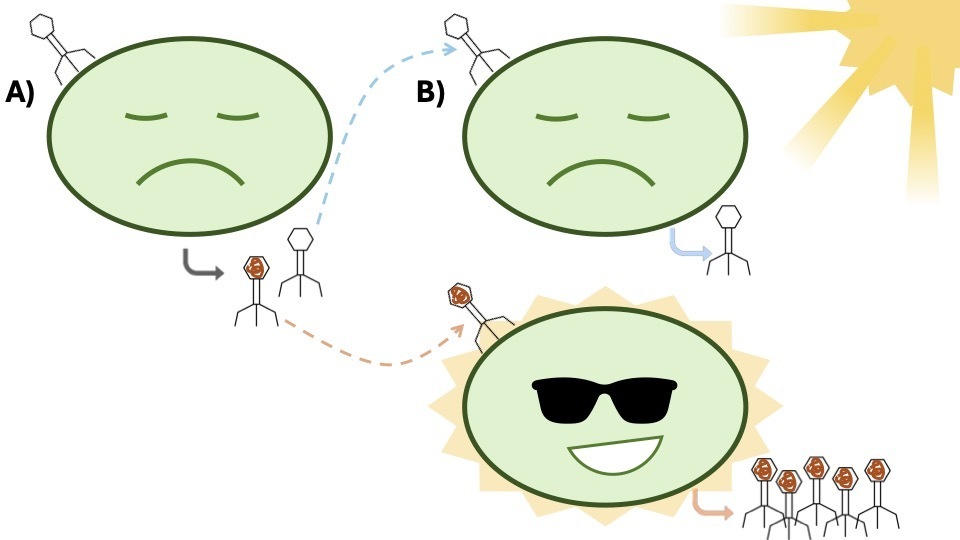

Cyanobacterial phages commonly encode a gene related to photosynthesis, which helps their hosts to continuously access energy from light, even while infected. Researchers found something unexpected when they contrasted the abundance of phages infecting Cyanobacteria with and without this gene. Contrary to expectations, the phages without this photosynthesis-related gene were much more abundant than the phages with the gene.

This runs contrary to what many scientists would have assumed. This gene is one of the best-studied examples of the AMG phenomenon and is considered critical to the cyanophage playbook. If this gene is so helpful to viral infection outcomes, why aren’t the viruses that have it more abundant?

The authors then examined the viruses of the two other ecologically important groups considered. For the methanotrophs, they looked at phages containing a gene critical for methane consumption and for Nanopelagicales, a gene that helps these bacteria process toxic compounds. For both of these groups, the same trend held true: viruses containing these important genes were far less abundant than those that did.

This raises the question of what these genes are actually doing for their viral hosts. The prevailing theory has been that they increase viral fitness by improving the replication of phages during infection. But if these viruses are not more abundant than their non-AMG-containing counterparts, what does that mean for this hypothesis?

To further explore this discovery, researchers looked at evolutionary patterns in the viruses over time. When a gene is beneficial to an organism, it will gradually become more common in the population. Genes that show signs of this kind of positive selection are inferred to be providing an advantage to the organisms encoding them. Genes that seemed to be positively selected for were mostly related to the viral structure and function. One, however, was an AMG—the same gene related to methane metabolism that had been shown in the previous analysis to be present in relatively uncommon viruses.

This is curious—why would a gene that seems to be “selected for” be present only in relatively rare viruses? The answer is yet unknown. Results that run contrary to existing scientific paradigms are the most exciting ones for researchers. The research inspired by the questions arising from this paper will surely be fascinating.

Link to the original post: Zhou, Z., Tran, P. Q., Martin, C., Rohwer, R. R., Baker, B. J., McMahon, K. D., & Anantharaman, K. (2025). Unravelling viral ecology and evolution over 20 years in a freshwater lake. Nature Microbiology, 10(1), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01876-7

Featured image: UW-Madison Environmental Remote Sensing Center, image processing by Jon Chipman https://www.nsf.gov/news/mmg/mmg_disp.jsp?med_id=76172&from=