Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbes can help create ‘universal’ blood type O

You may have noticed the Red Cross blood donation centers set up near hospitals, community functions, and their mobile donation vans. These donation drives are critical for maintaining a good supply and enough storage of all blood types. They ensure that all blood types are available in hospitals whenever they are most needed – in case of emergencies, surgeries, or when a patient with chronic illness requires treatment. One of the major issues these centers face is blood type incompatibility. A transfusion between unmatched blood types can lead to catastrophic immune system responses, thus making donor and recipient pairing an arduous task. This challenge creates issues in the provision of emergency care and bloodstock, particularly for uncommon blood types.

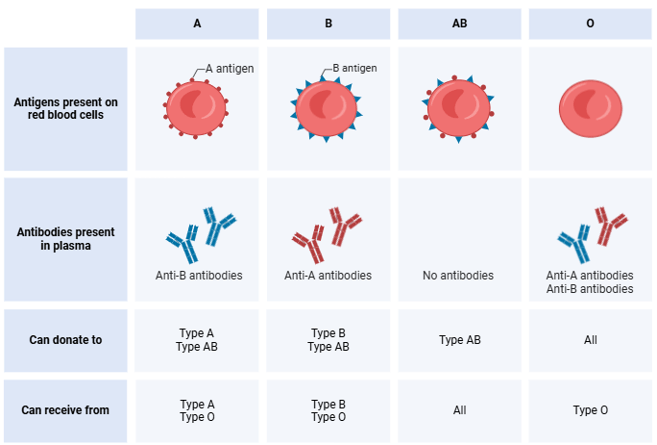

Certain antigens, labeled A, B, and O, identify the different blood types. These antigens are intricate sugar molecules found on the surface of red blood cells. Type O blood has neither antigens, AB has both, type B has B antigens, and type A has A antigens. If these antigens are transfused into someone with antibodies against them, it may cause immunological responses. E.g. if someone has blood type A, it means they have antibodies against blood with the B antigens and vice versa. Blood from donors of kinds A, B, or AB, cannot be given to a person with type O blood (anti-A and anti-B antibodies). O however, can be given to anyone and is seen as universal donor blood.

Scientists have been interested in ABO-universal blood—which can be safely transfused into anyone, regardless of blood type—for many years. This idea, called ECO-blood (Enzymatically Converted to O universal), has the potential to completely transform transfusion therapy and eliminate compatibility issues and blood shortages. Despite the successful conversion of A and B blood to type O in past studies, some safety concerns came up. In some cases, the plasma of the recipients reacted unexpectedly with the modified blood, suggesting an incompatibility issue. This happened even though nearly all of the original A and B antigens had been removed. So putting this concept into clinical reality has proven difficult despite a few advances.

A recent study provides fresh insight into the possibilities of using enzymes to convert blood types A, B, and AB to ECO-blood, providing a more direct route to this objective.

The researchers turned to an unexpected source of inspiration for this study: The human gut microbiota. They specifically looked into the bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila, which can grow by degrading mucins, complex proteins, and sugars that resemble the intestinal walls’ ABO antigens.

By studying the enzymes produced by A. muciniphila, the researchers discovered a highly efficient toolkit for breaking down both the core and extended forms of A and B antigens on red blood cells. These extended antigens were largely overlooked in earlier studies but were now found to play a critical role in compatibility issues. By targeting these extended antigens, the researchers significantly improved the compatibility of treated red blood cells in laboratory tests.

To put it into numbers: a previous study shows that even after using a cocktail of enzymes to remove A and B blood markers from red blood cells, 18% of plasma from B donors and 55% from O donors still reacted negatively when tested against these treated cells. This shows that the blood was still not fully compatible and something was still triggering a negative reaction. In the current study, removing both the B antigen and its extended variants reduced incompatible reactions with O-donor plasma to less than 9% and any remaining reactions were weaker. Similarly, when both the A marker and its extended version were removed from A-type blood cells, compatibility improved, and the severity of reactions decreased compared to just removing the A marker alone.

Why are there still negative reactions, you might ask? Other factors, such as variability between individuals in antibody profiles may contribute, as no person is the same. Another explanation by the researchers is that the enzymes used to change the blood type might accidentally expose other hidden markers that the immune system can detect. A third hypothesis is that there might be versions of the antigens that are resistant to these enzyme treatments and thus can not be removed this way. So, further research is needed to fully understand and address these issues.

The results of the study are a significant step in the production of ABO-universal blood. The recently discovered enzymes not only increase the effectiveness and scope of antigen removal, but they also function in realistic settings that make clinical application more feasible. This means that they operate under mild conditions without additives, and can convert a high concentration of red blood cells in a short amount of time (30 minutes).

Despite the hurdles, the work shows how these bacteria in our gut can be a gold mine for new medical innovations. And the great news is that, as well as being used in blood transfusions, these enzymes could also be used in organ transplants, where ABO incompatibility is a major problem.

Link to the original post: Jensen, M., Stenfelt, L., Ricci Hagman, J. et al. Akkermansia muciniphila exoglycosidases target extended blood group antigens to generate ABO-universal blood. Nat Microbiol 9, 1176–1188 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01663-4

Featured image: Bing image creator