Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Bioheist: A tale of intranuclear bacteria

Deep in the ocean, where the light barely reaches, life still thrives. Schools of fishes, squids, and -down in the dirt- mollusks, live and die in their own world, barely touched by humans. But there is more, of course. Protozoans, bacteria and viruses swarm around as well, often-times infecting bigger organisms for their own gain. Today, we focus on one of these bacteria. Its name is Candidatus Endonucleobacter, but let’s call it Ca.En for short. Somewhere deep in the ocean floor, Ca.En, a single small cell, is about to commit a huge heist, one that will let it reproduce into the thousands, and live like a king for a while.

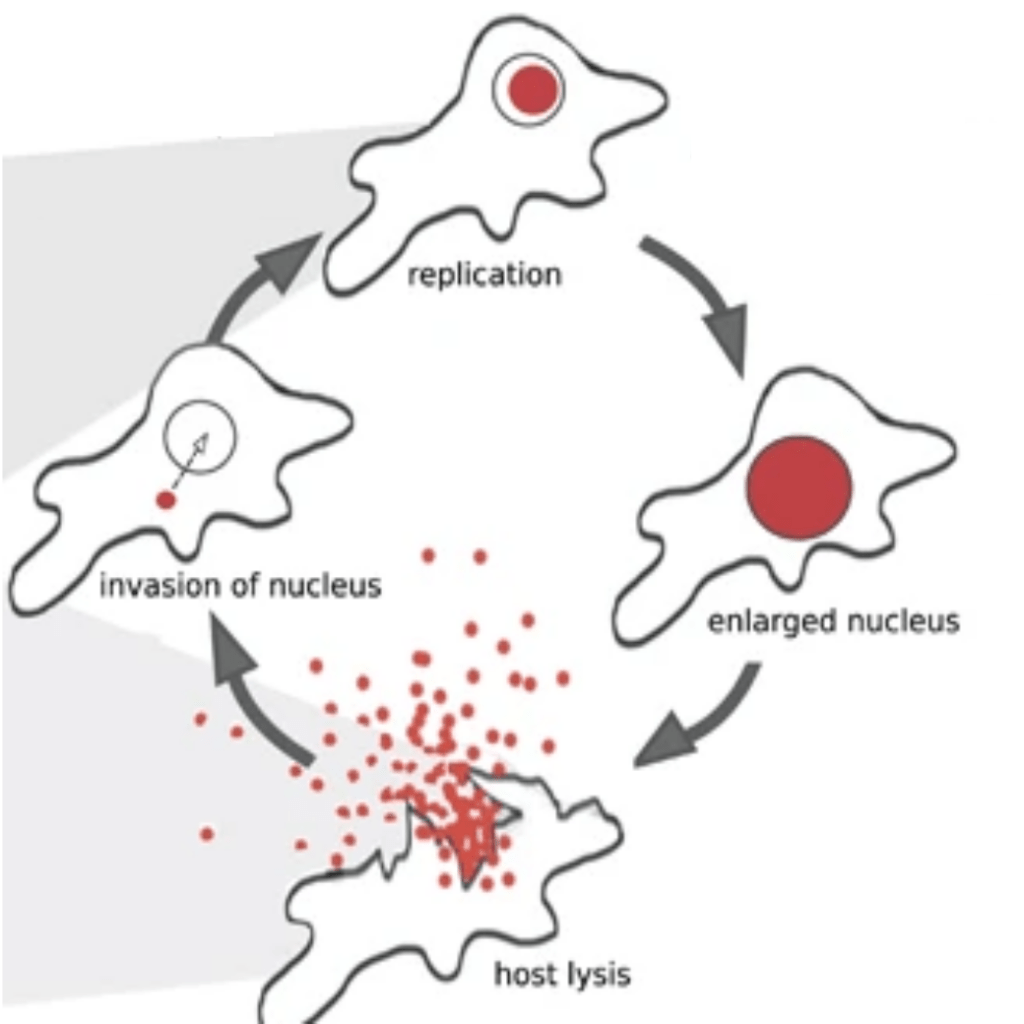

First things first, Ca.En has to find a host to infect. There are several species of Candidatus Endonucleobacter, some of which prey on deep-sea mussels, a type of mollusk. Each species has been reported to infect a specific species of the mussels, but they do this in similar ways. Once the bacteria has found its target, it infects a cell of the mollusk, finding a way through the membrane of the bigger eukaryotic cell. But it does not stop there. It then infiltrates the nucleus, where the DNA is stored, replicated, and transcribed into RNA. This is very unusual for bacteria. Viruses do this often, as they require the genetic machinery of the cell to replicate. But most of the stuff that bacteria can eat is in the cytoplasm. Ca.En does not really need much from the nucleus, it is a convenient hideaway at first. But it needs to eat, because there, that single bacterial cell will reproduce until they reach numbers close to 80.000 bacteria, and the nucleus of the mollusk’s cell will swell until it cannot contain the bacteria and bursts.

Originally, it was thought that Ca.En consumed the DNA within the nucleus, but this is likely incorrect. Instead, Ca.En takes care not to upset the cell it lives in, so it can take up nutrients that will be stolen for Ca.En’s gain. Instead, the bacteria transcribes various genes to kickstart the process of moving sugars and fats into the nucleus of the eukaryote, so that the bacteria can then consume that. In the meanwhile, it lets the eukaryotic cell continue to do its thing, unimpeded.

But of course, the eukaryotic cell realizes something has gone wrong. It sounds the alarm. It activates the genes that begin a pathway to activate the last resort against malfunction: Apoptosis, or programmed cell death. These genes generate proteins known as caspases, which kick down a stream of mechanisms to dismantle and kill the cell from within. But Ca.En knows this is coming, and knows what to do.

In Ca.En’s genome there is the information to create proteins known as inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs). These bind caspases, so the caspases cannot perform their job of kickstarting cell death. Ca.En begins producing these early on. The eukaryotic cell, however, realizes that there is a problem still, and creates more and more caspases, of different kinds. In response, Ca.En activates more and more genes to create different IAPs and block cell death, while it reproduces into the thousands within the nucleus. Each species of Ca.En has different IAPs, and different numbers, but the idea is the same. Hold off cell death as long as possible to grow in numbers.

But all good things must come to an end, and that is the case for these bacteria. Cell death is inevitable, as the now 80.000 bacteria crowd the swollen nucleus, having eaten all the nutrients from the eukaryote. The mollusk’s cell eventually dies, and the bacteria are released into the ocean waters, each to float away, ready to find a new host whose expense to thrive upon.

Source: Modified by the author from: Schulz, F., Lagkouvardos, I., Wascher, F. et al. Life in an unusual intracellular niche: a bacterial symbiont infecting the nucleus of amoebae. ISME J 8, 1634–1644 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.5

This tale of bioheist is at an end here, and I hope you found it as compelling as I did. However, I want to briefly mention the experiments that allowed scientists to reveal to us all this information, because it is as interesting as their findings. Mollusks were collected and analyzed, visualizing the cells of both them and the bacteria infecting some of their cells. Using lasers, they opened up single cells and their nuclei, to reveal the world inside and extract the DNA and RNA of cells at different stages of Candidatus Endonucleobacter infection. This allowed them to see the bacterial machinery to import food into the nucleus, as well as the arms race between the mollusk’s caspases, and the bacterial IAPs, and how it escalated over the course of infection. Moreover, the scientists confirmed the IAPs that Ca.En used come from the mollusk’s genome itself, having been “stolen” at some point in the past, and preserved in the bacterial genome as they provided an advantage throughout the infection.

Link to the original post: Porras, M.Á.G., Assié, A., Tietjen, M. et al. An intranuclear bacterial parasite of deep-sea mussels expresses apoptosis inhibitors acquired from its host. Nat Microbiol 9, 2877–2891 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01808-5

Featured image: Extended data Figure 1F from Porras, M.Á.G., Assié, A., Tietjen, M. et al. An intranuclear bacterial parasite of deep-sea mussels expresses apoptosis inhibitors acquired from its host. Nat Microbiol 9, 2877–2891 (2024)