Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbe F(ungus) v/s Microbe B(acteria)

Tuberculosis (TB) is a highly infectious airborne disease caused by the bacillus bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). The most common site of TB infection is the lungs (pulmonary TB), however, it can also occur in the brain, kidney, larynx, oral cavity, bones, and joints. Mtb is an extremely adaptive bacterium and is one of the most difficult bacteria to kill. Mtb infection can interact with the human microbiome and cause an imbalance in immunological and overall health. While antibiotic treatments are available for TB, the longer treatment time and the development of drug resistance in Mtb necessitate the development of novel therapeutics.

Considerable efforts have been made to screen various compounds that will help shorten the duration of Mtb treatment. A great option is to screen the natural environmental reservoirs of Mtb, such as the grey decomposition layer below the active growth layer of Sphagnum peat bogs. Peat mosses of the Sphagnum genus are closely linked to a complex population of microorganisms that live on their surface and in their tissues, forming a complex Sphagnum microbiome. Bacterial and fungal species coexist in this microbiome and struggle for scarce nutrients released when the peat moss cell walls break down. Since this habitat supports the largest concentration of Mycobacteria discovered anywhere in nature yet, it makes sense for the co-inhabiting fungi to produce secondary metabolites that will kill the bacteria and improve their competitiveness and survival.

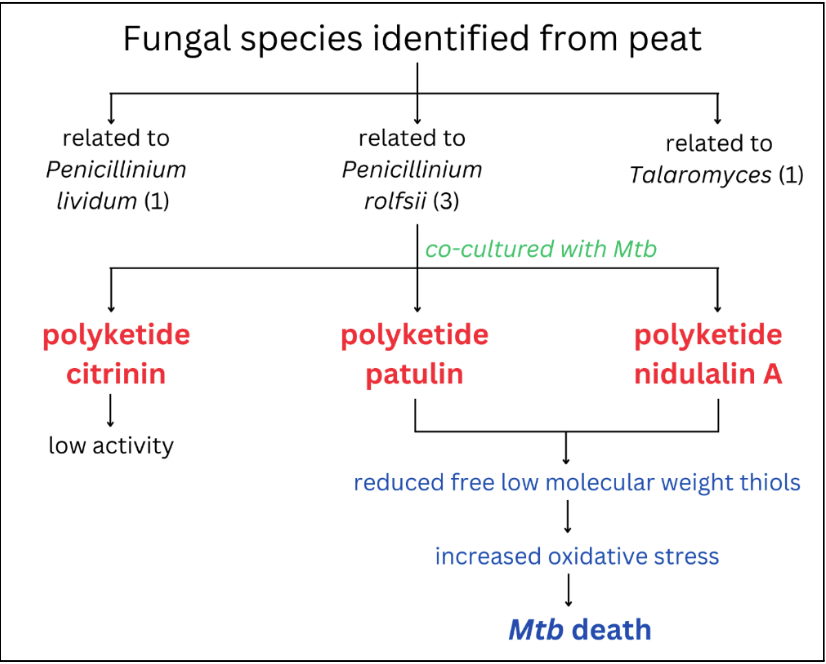

Malhotra and his team of researchers screened 1500 environmental fungal isolates from sphagnum peat moss. The fungal isolates were co-cultured with Mtb, and it was found that 5 fungal isolates could kill Mtb. In fact, this lethal effect was only seen when the fungi were co-cultured with Mtb, whereas no other bacteria died in their presence but Mtb. Intrigued, the researchers wanted to know what types of fungal species had this effect. They sequenced these lethal fungi and found one was related to Penicillium lividum, three isolates were related to Penicillium rofsii, and the last isolate was related to Talaromyces sp.

Through analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), a group of genes that collaborate to create these specialised anti-TB metabolites, the researchers found the culprit. The compounds produced by all 5 fungal species were polyketides, namely citrinin (by fungal species related to P. lividum), patulin (by fungal species related to P. rofsii), and nidulalin (by fungal species related to Talaromyces). They tested these metabolites and found citrinin had low activity against Mtb, so it was excluded from further experiments.

Further studies uncovered the mechanism of action of these polyketides. By profiling and analysing the genes of Mtb, the researchers found these compounds activated the thiol stress response pathway of Mtb. The thiol stress response is a pathway adopted by cells that protects them against oxidative stress by activating the hypoxia (oxygen deficiency) response in cells. The indiscriminate and irreversible oxidation of protein thiols and glutathione depletion are the outcomes of excessive oxidative stress that lead to cell death. The presence of fungal polyketides in the Mtb environment upregulated signature genes involved in balancing the thiol stress in Mtb. Further, these DNA studies also led to the observation that vital thiols, like mycothiol and ergothioneine, are reduced in the presence of these fungal polyketides. Mycothiol plays a significant role in protecting the Mtb cells against oxidative stress, and the lack of these protective thiols causes Mtb to suffer from reactive oxygen damage (DNA and protein damage).

Overall, these findings imply that drugs that target thiol homeostasis may have a major effect in eliminating the most challenging–to–kill Mtb. A team of researchers led by G.B. Coulson has previously targeted the thiol stress pathway in acidic conditions in Mtb to study potential antibiotic compounds, proving its future translatability.

Link to the original post: N. Malhotra, S. Oh, P. Finin, J. Medrano, J. Andrews, M. Goodwin, T.E. Markowitz, J. Lack, H.I.M. Boshoff, and C.E. Barry III. Environmental fungi target thiol homeostasis to compete with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS Biology, 22(12), e3002852, December 2024. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002852.

Featured image: Created by the author using Canva

Additional resources:

M. Nguyen, P. Ahn, J. Dawi, A. Gargaloyan, A. Kiriaki, T. Shou, K. Wu, K. Yazdan, V. Venkataraman. The interplay between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and human microbiome. Clinica and Practice, 14(1), 198–213, January 2024. DOI: 10.3390/clinpract14010017.

Q. Chai, Y. Zhang, C.H. Liu. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An adaptable pathogen associated with multiple human diseases. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 8, 158, May 2018. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00158.

J.E. Kostka, D.J. Weston, J.B. Glass, E.A. Lilleskov, A.J. Shaw, M.R. Turetsky. The Sphagnum microbiome: New insights from an ancient plant lineage, New Phytologist, 211 (1), 57–64, July 2016. DOI: 10.1111/nph.13993.

S.P. Baba, A. Bhatnagar. Role of thiols in oxidative stress. Current Opinion in Toxicology, 7, 133–139, February 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.cotox.2018.03.005.

G.B. Coulson, B.K. Johnson, H. Zheng, C.J. Colvin, R.J. Fillinger, E.R. Haiderer, N.D. Hammer, R.B. Abramovitch. Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensitivity to thiol stress at acidic pH kills the bacterium and potentiates antibiotics. Cell Chemical Biology, 24(8), 993–1004, August 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.06.018.