Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Why Does Tuberculosis Have So Many Survival Tricks Up Its Sleeve?

What makes Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) so adept at outsmarting medical science, even with over 20 antibiotics and a century-old vaccine like BCG in our arsenal? Despite these measures, this bacterium holds the grim title of the deadliest infectious disease agent, causing almost 1.5 million deaths annually. The scenario worsens with the increasing prevalence of drug-resistant strains and the deadly synergy between TB and HIV co-infections.

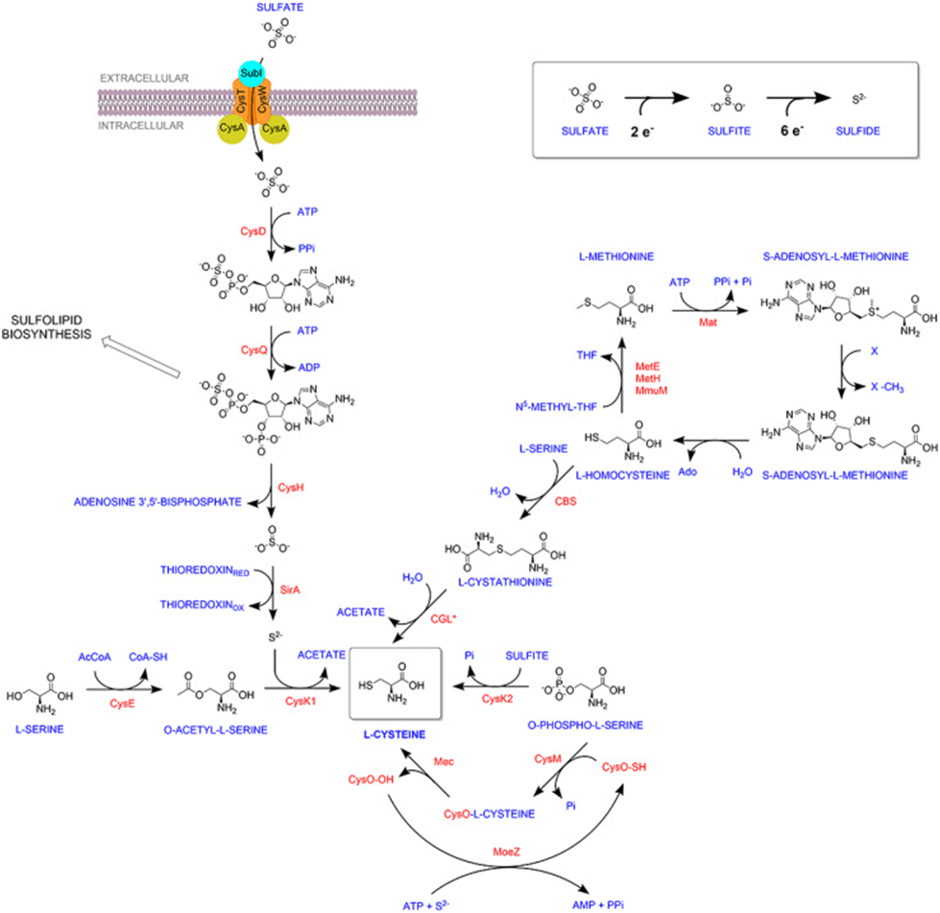

Mtb’s survival strategy is a masterclass in adaptability. Inside its human host, it endures an unforgiving environment marked by nutrient scarcity, acidic surroundings, and the toxic assault of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). To navigate this minefield, the bacterium produces mycothiol and ergothioneine—antioxidants that neutralize oxidative damage. These molecules rely on L-cysteine, an essential building block synthesized by Mtb using pathways that are absent in humans. This absence creates an opportunity to target Mtb-specific processes without harming the host, thus presenting a promising avenue for developing targeted antibiotics.

Mtb uses multiple enzymes and pathways to synthesize this vital L-cysteine molecule. Three L-cysteine synthases—CysK1, CysM, and CysK2—operate together or independently to ensure a steady supply. While CysK1 relies on sulfur derived from sulfate through the sulfur assimilation pathway, CysM and CysK2 use alternative substrates and mechanisms. Mtb also has a backup reverse transsulfuration pathway that converts L-methionine to L-cysteine. This metabolic redundancy raises fascinating questions: why does Mtb invest in so many routes for one molecule? Are these pathways truly interchangeable, or do they serve distinct roles depending on the cellular context?

Well, a recent study conducted at the CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India, by Khan et al. 2024, delved into these mysteries, focusing on the non-canonical synthases, CysM and CysK2, to decipher their roles in Mtb’s survival under stress. Their findings reveal that these enzymes are far from redundant. While mutants lacking either enzyme grew normally in nutrient-rich laboratory conditions, their growth faltered under stress conditions mimicking the host environment. The mutants struggled to withstand oxidative onslaughts, pointing to the heightened importance of L-cysteine-derived antioxidants during host-induced stress.

Transcriptomic analyses identified differentially expressed genes under various stress conditions, revealing significant changes in intermediary metabolism, nitrogen, sulfur, and lipid biosynthetic pathways. Stress conditions caused a significant reshuffling of Mtb’s gene expression, with sulfur assimilation and L-cysteine biosynthesis genes taking center stage. When oxidative stressors like cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) were introduced, the differences between the mutants and the wild type became striking. Over 30% of Mtb’s genes showed differential expression, showcasing the distinct roles of CysM and CysK2. Moreover, the mutants exhibited lower levels of key antioxidants, confirming the enzymes’ essential roles in maintaining redox balance.

Interestingly, supplementing the stressed mutants with external L-cysteine restored their survival, demonstrating the bacterium’s ability to scavenge this molecule from its surroundings. However, this raises a paradox: if L-cysteine is available in human plasma, why can’t the bacterium rely on host-derived sources during infection? This inability suggests that Mtb’s niche within the host may limit access to L-cysteine or that its transport mechanisms are insufficient under natural conditions. The significance of CysM and CysK2 extends beyond redox balance. Deleting these enzymes not only disrupted antioxidant production but also amplified the bacterium’s susceptibility to oxidative stress. This dual impact—impairing antioxidant defense and secondary metabolism—renders CysM and CysK2 highly attractive drug targets.

Experimental findings further validated the therapeutic potential of targeting these enzymes. Inhibitors designed to block CysM activity demonstrated bactericidal effects in induced dormancy models of Mtb, where nutrient starvation mimics the conditions Mtb faces in latent infections. The absence of homologous L-cysteine biosynthetic pathways in humans further strengthens the case for these enzymes as selective drug targets. Going deeper, researchers found that the absence of CysM or CysK2 undermined Mtb’s ability to counter immune-mediated redox stress. Mutants displayed reduced survival in macrophages capable of generating ROS and RNS. This vulnerability was starkly evident in experiments involving genetically modified mice lacking key immune defense mechanisms. In such hosts, the mutants regained some survival advantage, confirming that CysM and CysK2 are critical for resisting the oxidative barrage launched by the immune system.

These findings not only showcase the nuanced interplay between Mtb and its host but also pave the way for cutting-edge therapies. Targeting the non-canonical L-cysteine synthases could simultaneously disrupt Mtb’s redox homeostasis, antioxidant production, and ability to thrive in hostile environments. Moreover, combining such targeted inhibitors with existing TB drugs could amplify therapeutic outcomes, particularly against drug-resistant strains or latent infections. Yet, the story is far from over. Why does Mtb persist in maintaining such metabolic redundancies? Is the L-cysteine pool produced by different pathways functionally compartmentalized for specific downstream processes? Could targeting these enzymes inadvertently trigger compensatory mechanisms, or is there a way to outmaneuver the bacterium’s adaptability? Solving these may not only revolutionize tuberculosis treatment but also shed light on broader principles of pathogen evolution and host-pathogen interactions. One must wonder: how many more secrets does Mtb hold, waiting to be unraveled?

Link to the original post: Khan, M. Z., Hunt, D. M., Singha, B., Kapoor, Y., Singh, N. K., Prasad, D. V. S., Dharmarajan, S., Sowpati, D. T., de Carvalho, L. P. S., & Nandicoori, V. K. (2024). Divergent downstream biosynthetic pathways are supported by L-cysteine synthases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eLife, 12, RP91970. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91970

Featured image: ChatGPT