Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Designer cocktails: a new frontier in… medicine?

Viruses infect nearly every organism on Earth, including bacteria in our bodies. Scientists are exploring bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—as tools to fight harmful pathogens, a strategy known as “phage therapy.” If you’re interested in reading more about phage therapy and its history, check out this article, or Tom Ireland’s fascinating book The Good Virus.

Like humans, bacteria have an adaptive immune system and can develop resistance to phages that have infected them before. This developed immunity prompts phages to evolve new infection mechanisms in a microbial “arms race” (see this article for an interesting example of how this arms race works). This co-evolution results in a diversity of both phages and hosts that complicates phage therapy: a phage that infects one bacterial pathogen may not be effective against a closely related one. Effective phage therapy will require customized treatments, relying on rapid and accurate predictions of phage-host compatibility using genetic data – something that currently lies beyond our capabilities.

To address this problem, researchers designed an ambitious experiment, assembling diverse bacterial (403 bacterial strains from the genus Escherichia) and phage (96) collections to test 38,688(!!!) pairs.

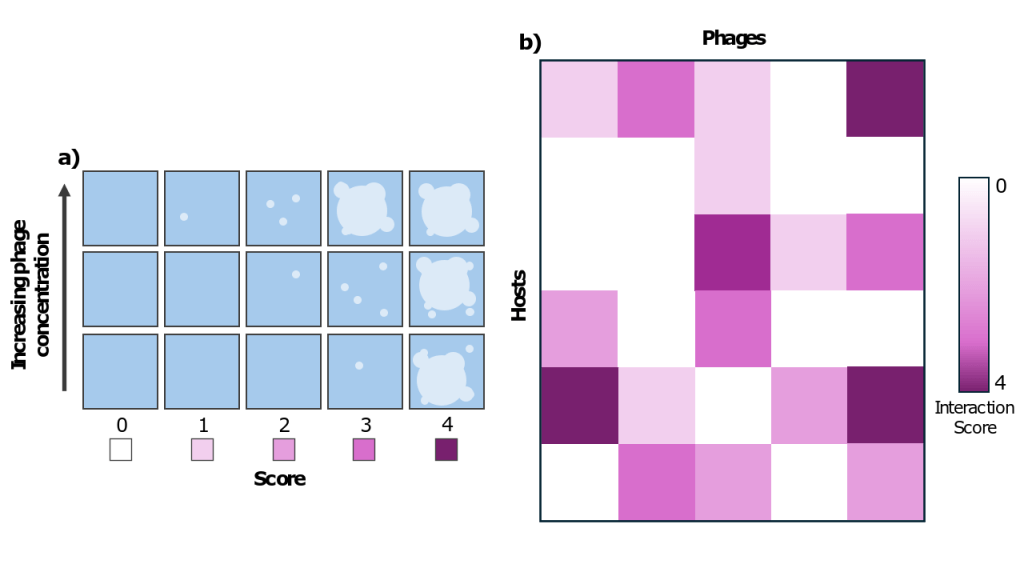

Microbiologists typically use something called a “plaque assay” to determine whether a given phage infects a given bacterium. To do a plaque assay, they create something called a “lawn” of bacteria: a dense population of bacteria growing on agar. Then, they add some phage on top. If a clear spot (“plaque”) develops where the bacteria are all dead, they have been killed by successful phage infection. For each pair, the scientists used a ranking system to categorize how successful infection was. They compared differences in plaques between different initial phage concentrations to determine how easy it was for a phage to infect a given host. They created a ranking system from 0-4 to encode infection success, 0 meaning no infection, and 4 meaning infection at every phage concentration. Using this code, they created a matrix of all interactions.

b) By adding each phage to each bacterium, the authors created a matrix of interactions between phages and hosts, ranked according to the system outlined in a).

The authors examined both phage and bacterial genomes to identify factors influencing infection outcomes. They found that closely related phages are more likely to infect the same bacteria due to shared receptor-binding proteins, which enable attachment to bacterial surfaces. On the bacterial side, “phage adsorption factors” (genes related to how phages enter the cell) were key determinants of susceptibility.

Surprisingly, the bacterial immune system does not seem to be a major determinant. Only two genes related to anti-phage defense were significantly correlated to infection outcomes. The number of anti-phage defense genes that a genome encoded was not significantly correlated to the number of phages that could infect it, although it was slightly negatively correlated to how extreme infection outcomes were. This is surprising because many bacteria carry extensive anti-phage defense machinery (this is the bacterial immune system), which is energetically costly to maintain, and the general assumption has been that more anti-phage defense means more phage resistance. This may not turn out to be true, raising the question of what these defense systems are really doing.

To validate their findings, the researchers used patient-derived E. coli strains to design “phage cocktails” of three phages tailored to each strain. For some bacteria, this recommender system was able to design custom phage cocktails that together had a 91% success rate of killing the bacterium. Other bacteria were harder to design custom cocktails for and the recommender system was only able to recommend a more generic cocktail. These generic cocktails had only a 78% success rate, whereas a baseline cocktail of the three phages that infected the greatest number of bacteria had an 81% percent of killing the host.

Together, the insights of this work represent progress on our ability to predict infection outcomes among the diversity of hosts and phages in the environment and the potential to leverage those predictions to improve phage therapy treatment.

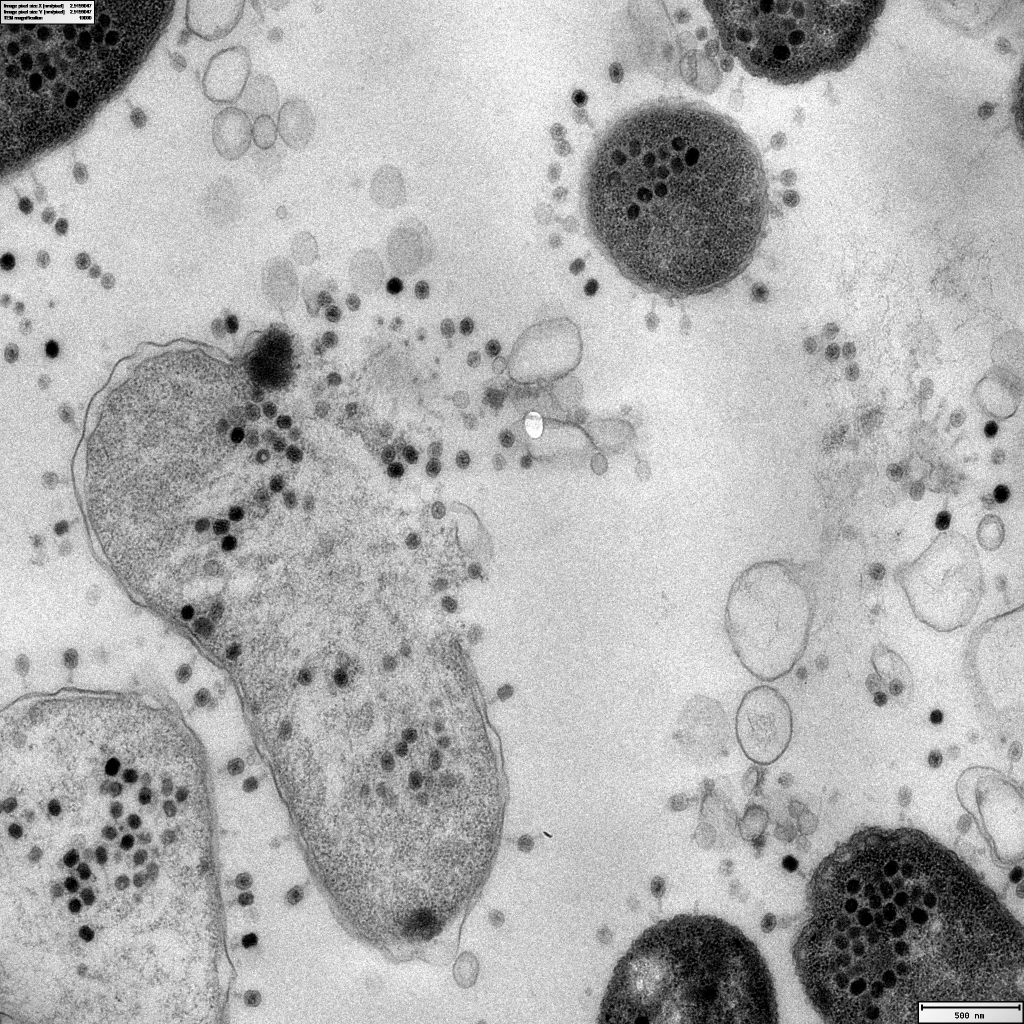

Featured image: Source link: https://www.reddit.com/r/electronmicroscope/comments/12pe9zb/thats_why_we_love_electron_microscopy_it_shows/