Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Hot to Go! Frogs recoup from deadly fungus in hot bricks

Winter is a time for beautiful things like freshly fallen snow, relaxing around the fire, and palpable holiday excitement. However, along with season’s greetings, winter brings seasonal outbreaks of the flu and common cold. Luckily, these diseases aren’t something that modern medicine can’t handle; an annual vaccine and good hygiene are enough to prevent most healthy adults from getting sick. If you do catch a cold in the winter, at least you can enjoy your favorite soup and watch the newest cheesy holiday movie while resting under a cozy blanket. These comforting activities aren’t just a distraction; they help your body recover from illness.

Stone-Cold Killer

Pathogens can’t take the heat, so, as part of their immune response, humans and other warm-blooded animals will have a fever when sick. But cold-blooded animals like amphibians and reptiles cannot generate their own body heat. Instead, they must rely on the environment to raise their temperature, which can be challenging during colder months. This method of thermoregulation has proven to be a fatal flaw for amphibians.

Winter outbreaks of chytridiomycosis, an infectious disease in amphibians, have driven over 90 species to extinction and continue to affect hundreds more. The disease is caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), a fungus from Asia that spread worldwide through human trade routes. This fungus takes root quickly in new environments and is almost impossible to remove. Without time to adapt to this invasive pathogen, amphibian populations will continue to decline. The only way to save species endangered by chytridiomycosis is to find a way for affected animals to coexist with Bd. A recent study offers a simple way to give afflicted amphibians some reprieve.

Amphibians need to turn up the heat to tip the scales back in their favor. Bd is sensitive to heat, moderate increases (from 17.0 to 22.0 °C) already decrease Bd infections. So even small increases in body temperature can lessen the severity of chytridiomycosis in infected animals. A research group in Australia devised a way to exploit this weakness of Bd. They hypothesized that artificial thermal shelters would give wild amphibians a warm resting place to overcome chytridiomycosis and build immunity to the disease. Installing these warm shelters in areas impacted by Bd could be the key to saving endangered species from extinction.

Heating Things Up

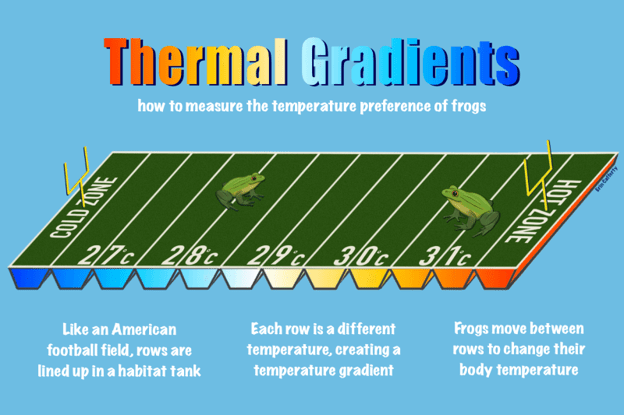

Before deploying thermal shelters in the wild, researchers needed to know if their theory would work in a laboratory. To simplify things, they used a single amphibian species to test their hypothesis: the green bell frog. Bell frogs are known to bask in the sun on warm days and became endangered in Australia after the local emergence of Bd, making them a good candidate for the experiment. Researchers separated frogs with Bd infections into tanks with one of three temperature conditions: low, average, and multiple temperatures in a thermal gradient.

The frogs in the thermal gradient tank can move between high and low-temperature areas, a clever way to see if infected frogs would benefit from access to warm shelters in the wild. What the researchers saw was encouraging. Infected frogs in the thermal gradient tank were the fastest to recover. Frogs in the average-temperature tanks recovered slowly without the ability to thermoregulate. As expected, frogs in the low-temperature tanks never got better and had the most intense infections out of all three conditions. Further testing showed frogs that recovered from a past infection were more likely to survive a second Bd infection. After seeing success in the lab, it was time to put this idea to the test outside.

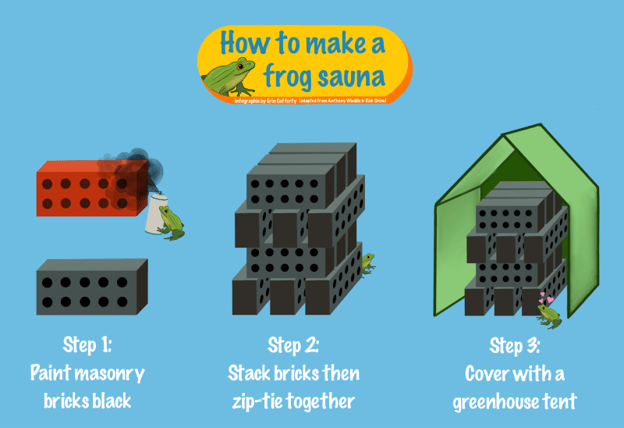

Seeing that warm shelters improved frog health in the lab, the research team had to get the same result in an outdoor experiment to prove their hypothesis. But proof alone wasn’t enough. Researchers knew their artificial thermal shelter needed to be cheap and easy to install to be used in conservation efforts. It turns out that a stack of ten-hole masonry bricks provided a perfect warm refuge for the bell frogs. Researchers put Bd-infected frogs in outdoor enclosures called mesocosms equipped with food, water, and budget-friendly brick shelters. The frogs remained in the mesocosms throughout winter until early spring.

Reference: “How to build a frog sauna” PDF by Anthony Waddle & Rick Shine

A Warm Send-Off

After 15 long weeks, the research group got their answer. Artificial thermal shelters can provide bell frogs relief from chytridiomycosis in the wild. Just as they saw in the lab, the outdoor bell frogs recovered from and developed residence to Bd thanks to thermal hotspots. Researchers found the frogs in the shelter 74% of the time during data collection, suggesting that it became their preferred hangout spot. Heated by sunlight, the thermal shelters made from masonry bricks thermal shelter proved to be a low-tech, low-cost method for achieving high-yield results. This study provided a huge step forward in managing Bd infections in the wild, and the authors hope their work inspires similar strategies to aid the recovery efforts of a wide range of endangered species.

Link to the original post: Waddle, A.W., Clulow, S., Aquilina, A. et al. Hotspot shelters stimulate frog resistance to chytridiomycosis. Nature 631, 344–349 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07582-y

Featured image: Photo credit: Anthony Waddle

From: https://x.com/AnthonyWaddle/status/1806076679783428393/photo/1