Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Herpes’ Route from the Nose to the Brain

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is an ailment that billions of people have to contend with. But the virus can do more damage than just creating pesky cold sores — it can also infect the brain.

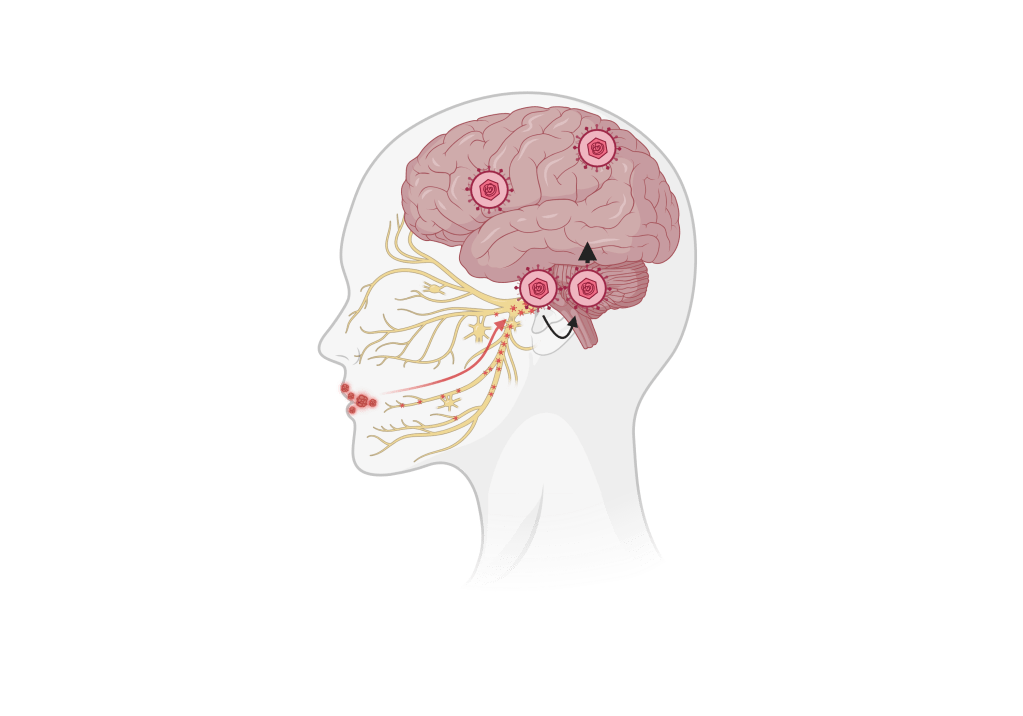

People can pick up HSV-1 from infected saliva or bodily fluids. From there, the virus can enter mucus membranes like your eyes, mouth, or nose. While the virus infection in skin cells causes cold sores, HSV-1 also spreads to nerve cells, which can remain dominant or become active depending on things like stress or weakened immunity.

In some cases, the virus can spread to your central nervous system. The central nervous system is like the body’s control center, composed of the brain and spinal cord. Because of the HSV-1’s ability to get into the brain, in recent years, it’s been proposed as a potential cause of Alzheimer’s disease – but researchers weren’t sure how the virus was spreading in the central nervous system. In a new study published in the Journal of Virology, researchers have uncovered how HSV-1 spreads within the brain and the potential link to long-term neurological issues, including Alzheimer’s.

The study used a mouse model to study how the virus spreads. When researchers infected the mice and examined different tissues to find the path of infection, they saw that neurons on the nose weren’t very infected, meaning the virus likely didn’t reach the brain through cells in the nose. They did find that areas of the brainstem – associated with cranial nerves and the hypothalamus – were infected and remained inflamed even after the infection was cleared. Both the brainstem and hypothalamus are critical for regulating things like stress, as well as serotonin. Chronic inflammation in these areas could permanently disrupt these functions, leading to disease.

The study also found that HSV-1 primarily travels along the trigeminal nerve, a cranial nerve that provides sensations from the face to the brain. From there, the virus can reach areas like the brainstem and hypothalamus but might limit its access to other areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is important for memory formation.

To better understand how HSV-1 infected the mice’s brains, they looked specifically at microglial cells, the primary immune cells in the brain. These cells can detect infections, respond to inflammation, and help clear out pathogens and cellular waste. After infecting the mice with HSV-1, researchers dissected different brain tissues and stained them with antibodies, which are like special dyes, that bind to markers of microglial activation and HSV-1 and show where immune activation and viral infection are taking place. The staining allows them to visualize areas in the brain where HSV-1 is present and immune activity is occurring. They saw that 7-days after infection was when most immune cells were activated, which also matched the time when there was the highest infection.

However, researchers also saw that microglial cells were activated in some brain regions as early as three days after infection, showing that different brain regions respond differently to HSV-1 infection. They also saw that immune cell activation could occur in areas where the virus wasn’t present, which could indicate cells are responding to infected or damaged cells nearby, and it shows that inflammation can happen in areas of the brain where the virus didn’t reach.

Abnormal activation of microglial cells causing chronic inflammation has been connected to Alzheimer’s disease, which could explain how HSV-1 infections are linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Reducing the risk of developing neurological diseases in those infected with HSV-1 will rely on preventing HSV-1 activation. However, as of now, most treatments require you to catch an outbreak early on, which can be difficult, and no medication completely prevents the reactivation of the virus.

While researchers still don’t fully understand how HSV-1 can lead to long-term illnesses, these findings are a good step to tracing the virus’s path from how we get to infectious saliva to Alzheimer’s disease.

Link to the original post: Niemeyer CS, Merle L, Bubak AN, Baxter BD, Gentile Polese A, Colon-Reyes K, Vang S, Hassell JE, Bruce KD, Nagel MA, Restrepo D. 0. Olfactory and trigeminal routes of HSV-1 CNS infection with regional microglial heterogeneity. J Virol 0:e00968-24. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00968-24

Featured image: Made by author in Canva.com