Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Bacteria use DNA cartwheels for survival

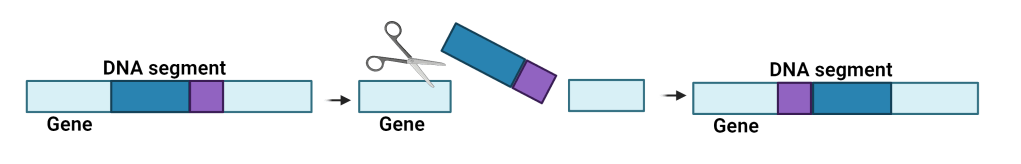

Most organisms have an arsenal of tools to increase their chances of survival — one of those tools is to change their DNA and gain new traits. There are numerous ways DNA can change, such as mutations, insertions, deletions— the list could go on forever. But single-cell organisms, like bacteria, can do something most other organisms can’t: genetic inversions. The inversions are sort of like genetic cartwheels, where sections of DNA will be cut out of the genome and then reinserted backward.

DNA inversions can change gene expression and function and have been shown to help bacteria evade host immune systems. Previous studies only found inversions outside of genes, in regions of DNA that don’t code for proteins (such as promoters). Inversions in this part of DNA can help influence gene expression, but they don’t directly change the function of a gene. But now, a new study found that bacteria also have inversions in genes, which can completely change their function.

To look for inversions, researchers investigated sequencing data from human stool samples. This sequencing data contains gene information from all DNA found in the stool, including DNA from bacteria, viruses, and human cells. They specifically looked at stool from people who had bone marrow transplants because they hypothesized bacteria living in these patients would have had to encounter a lot of stressors like chemotherapy and antibiotics that bacteria in healthy patients might not — and stressors promote mutations.

The researchers first used a more traditional method to find inversions, called PhaseFinder, which analyzes short pieces of DNA to look for flipped DNA segments. They looked at DNA sequences from a promoter of a gene known to invert from one type of bacteria commonly found in the human gut. They saw flipped promoters and found that inversions were more common in bacteria naturally found in the human gut than in the lab-grown strain. When looking at the promoters, the researchers also noticed inversions of short DNA sequences in the gene the promoter was driving, which is the first evidence of inversions within a gene.

In some cases, the inversions introduced an early stop codon, preventing the full protein from being made and possibly creating two proteins instead of one. In other cases, they might affect how the protein functions, but researchers cautioned that the proteins would need to be tested before any conclusions could be made.

The researchers knew that PhaseFinder has some limitations: repetitive DNA regions are difficult to map using short DNA sequences accurately and could lead to flipped regions of DNA being missed. To solve this problem, the researchers developed a tool called PhaVa. The tool uses long reads of DNA and maps them to a known genome sequence in both the regular and inverted position. If a segment matches the flipped position better, an inversion has happened in that location.

They tested the new tool on long-read datasets from bacteria in a sequencing database. They found examples of inversions happening both outside and inside genes in a variety of bacterial species, showing that many prokaryotes experience DNA flipping. When PhaVa was used to analyze DNA from the stool samples, they saw an even higher percentage of DNA flips, showing that bacteria in higher-stress environments are more likely to undergo inversions. The inversions also didn’t seem random. Inversions in genes responsible for DNA binding and DNA and RNA modifications were the most likely to have flipped segments of DNA.

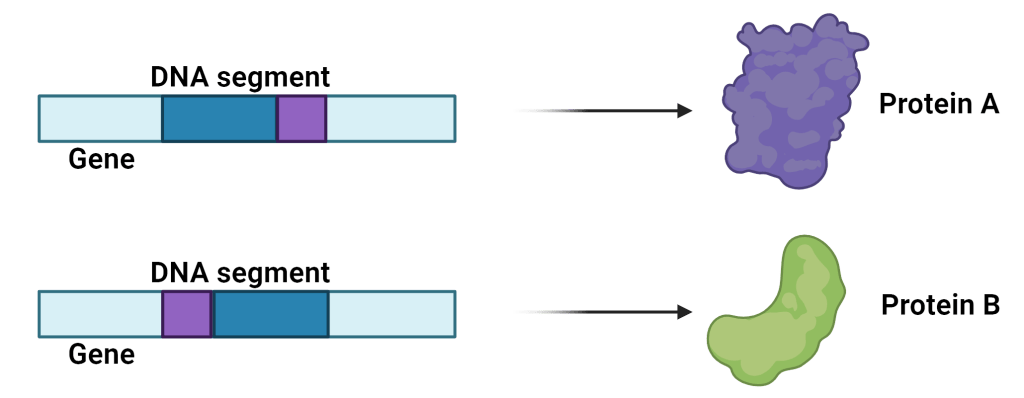

It is predicted that 169 out of 372 inversions would affect protein function. Proteins involved in cellular division, environmental stimuli responses, and gene expression were all expected to have different functions with an inversion and would expand the number of proteins a bacteria can make without expanding their genome size.

The researchers also saw that inversions in regions of DNA that don’t code for proteins were generally the same in a bacterial population: the DNA was either inverted or it wasn’t. But inversions in the coding region of a gene were different, within the same bacterial population, some had inversions in a region of a gene while others didn’t.

This study gives insight into a mechanism bacteria can use to increase their chances of survival and diversity in their genetic repertoire. How the inversions are happening, though? That’s a mystery for future researchers to solve.

Link to the original post: Chanin, R.B., West, P.T., Wirbel, J. et al. Intragenic DNA inversions expand bacterial coding capacity. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07970-4

Featured image: Image made by the author with Canva.com