Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Something in the water: Toxic waste and fungi

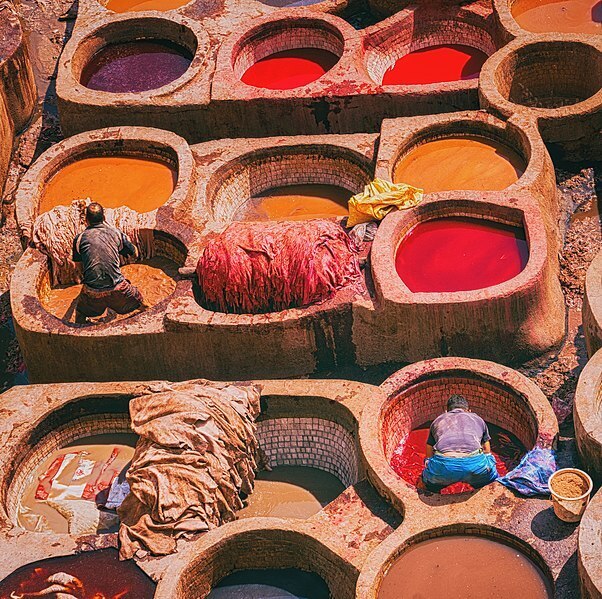

Leather doesn’t come cheap. Some people walk around with handbags that cost as much as the average monthly wage. But if the sticker price of a bag comes as a shock, that’s nothing compared to the environmental price.

For every tonne of skin processed, between 60 to 250 tonnes of wastewater is produced. The estimate varies so greatly because tannery techniques and regulations differ between countries. Less developed countries lack access to more efficient techniques, so their wastewater output is generally higher.

Tannery effluent is the technical term that describes this water, along with any pollutants left inside. Nitrogen-containing compounds, such as fats and proteins, have the potential to cause eutrophication of nearby bodies of water. This can destroy aquatic ecosystems. Salts and heavy metals are even more problematic — some are even known to cause cancer. That’s the last thing anybody wants floating around their local waterways. Could there be an efficient, cost-effective way to clean this water?

Researchers based at King Saud University conducted a study to find out if fungal bioremediation could help to purify tannery effluent. Bioremediation describes the process of using a biological organism (usually bacteria, fungi, or plants) to clean up environmental pollutants.

Scientists sampled water from a mangrove swamp in Tarout Bay and isolated 5 different types of salt-tolerant fungi. Like tannery effluent, mangrove water is very salty — a great place to look for fungi that thrive in salty conditions.

They set up different test groups using the fungi and 2 other bioremediating agents: dried vetiver grass roots and biochar. Biochar is a charcoal-like byproduct that comes from burning woody biomass, like agricultural or paper mill waste. Pollutants are removed from the water by adhering to the surface of these agents, a process known as adsorption — yes, that’s a “d.” Put simply, it’s a bit like magnets sticking to a fridge.

Glass tanks were filled with tannery effluent and treated with the following combinations: biochar alone, roots alone, biochar and roots together, each fungal isolate by itself, and each fungal isolate combined with both biochar and roots.

To evaluate the effectiveness of each treatment, ten different variables were measured: turbidity (a measure of clarity), salinity (a measure of salt content), total dissolved solids, total suspended solids, phenols (a type of organic pollutant), nitrogen, ammonia, heavy metals, biological and chemical oxygen demand (two methods of measuring the concentration of organic matter in wastewater).

The treatment with the most statistically significant effect was Emericellopsis fungus in combination with biochar and roots. It produced the lowest values for 6 of the 10 measured variables. All fungus/biochar/roots combination treatments performed better than fungus alone.

This is promising, but there are some limitations. Even the most effective treatment did not purify the water enough to meet local regulations. The authors suggest combining Emericellopsis with other known bioremediating bacteria and fungi might purify the water more effectively. It’s possible that even more efficient fungi are out there, yet to be discovered.

Awareness of the environmental impact of fast fashion is on the rise. This important study highlights one of the lesser talked about aspects of the fashion industry. It might be tempting to think of tannery effluent as a far-off problem. But ultimately, it doesn’t matter where in the world toxic waste is dumped. All water on the planet is connected through the same cycle. So when it comes to the environment, we’re all left holding the bag.

Link to the original post: Ameen, F., Alsarraf, M.J., Abalkhail, T. et al. Tannery effluent treatments with mangrove fungi, grass root biomass, and biochar. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 40, 249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-024-04055-2

Featured image: Workers dyeing leather at a tannery in Fez, Morocco. Image source: Mrinal Mohit, via Wikimedia Commons.