Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Can microbes transfer stress over generations?

Every year, millions of people around the world suffer from debilitating mental illnesses such as anxiety or depression. There are many types of medication and cognitive behavioral therapies that try to help manage symptoms of these conditions. However, an overwhelming amount of people each year are not responsive to these treatments, leaving them at the full mercy of their symptoms. What if we could treat anxiety and depression through other means? That is precisely the question that many labs around the world are asking.

A growing body of research in the field of microbiology is trying to understand the relationship between the microbiome (all the microorganisms that live in our bodies) and human behavior. Thus far, there has been consensus on the existence of a “gut-brain axis”, a bidirectional, biochemical pathway that connects the gut and the brain. The microbiome is regarded as a pivotal part of this connection. Yet, there are still many unknowns regarding what happens to the microbiome in the case of chronic mental disorders like anxiety or depression, or exposure to stress.

A recent study by a research laboratory in Switzerland decided to investigate whether being exposed to stress during early life could lead to changes in the microbiome of not just the original individuals that experienced the stress, but also their offspring. Previous work by different research labs has shown that being exposed to stress during early life can lead to individuals developing mental illnesses like anxiety.

In this study, investigators decided to use a model named MSUS (maternal separation with unpredictable maternal stress) that aims to simulate being raised in abusive or high risk households. In it, both the pups and their mother are separated and the mother is stressed unpredictably during their time apart. After exposing the first generation of mice to stress, male offspring were used for behavioral and microbiome testing, while female offspring were used to breed a second generation of mice. This generation would not be stressed and would be used to generate a final third generation of mice. With this experimental setup (see image below), the researchers hoped to see whether the microbial effects of stress experienced in the first generation, could be transferred via their offspring.

The results of this generational study were fascinating! The researchers found that there were microbiome differences induced by the stress and that these differences were transferred from mother to child. They also discovered that the microbiome differences were not transferred from father to child, even if they were kept in the same cage. This was somewhat expected, since it is known that the first significant exposure to microbes comes from our mothers during birth.

One of the microbiome changes they observed in the stressed mice was a decrease in several bacteria, including those in the family Ruminococcus, which are known for producing short-chain fatty acids (molecules important for maintaining gut health). They also found higher levels of Lachnoclostridium, which had been reported to be higher in other models of early life stress. These taxa were usually not detected in the controls, which suggested that being exposed to stress did not only shift the abundance of bacteria, but it changed which bacteria were able to colonize the gut in the first place.

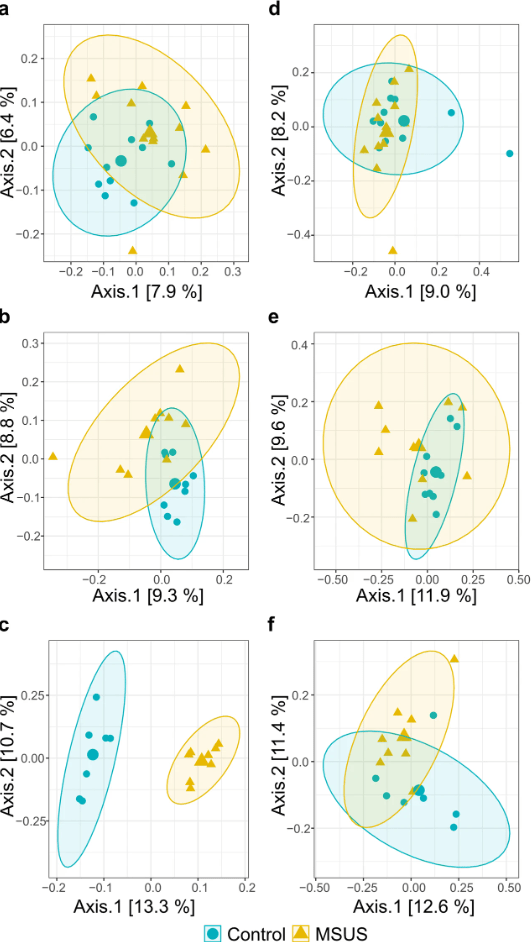

Fascinatingly, their results also showed that microbiome shifts in diversity persisted through each generation and in fact worsened in the last generation tested .

This can be observed in the image below, where the dots represent individual mice and the farther apart two points are, the more different their microbial community is. This was incredible because the only generation to be directly stressed by the researchers was the first one, yet each subsequent generation still inherited all the microbiome changes from their parents.

Overall, the researchers hypothesized that the reason why the generational changes persist is because the initial stress exposure leads to systemic changes in the gut and brain of the mice, which are then maintained throughout their life by their microbiome changes. The altered microbiota may then signal back to the host to maintain the negative behavior.

In conclusion, this study shows that stress and anxiety-like behavior are interconnected not just within the individual but also throughout their subsequent generations. This has interesting implications for the future of mental health treatment and also reproductive health. Our future may include new treatments that help not just treat an individual’s conditions, but help them prevent passing it on to offspring if they so choose.

Link to the original post: Otaru, N., Kourouma, L., Pugin, B. et al. Transgenerational effects of early life stress on the fecal microbiota in mice. Commun Biol 7, 670 (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06279-2

Featured image: Created by author using Canva Pro